(690-705)

In 690, Empress Wu Zetian declared that the Tang Dynasty had officially ended and established her own Zhou Dynasty in its stead. It is often referred to by historians as the Second Zhou Dynasty to prevent confusion with the earlier Zhou Dynasty (c. 1045-256 BC), although it is regarded more as an interruption of the Tang rather than as a dynasty in its own right. Thus Empress Wu became the only female sovereign to ever openly rule over China in its history. So forget Girl Power, it’s all about Wu Power!

Empress Wu began her political career as the concubine of Emperor Taizong but, through her cunning and sometimes rather ruthless tactics, eventually managed to usurp the throne after the death of her husband, Emperor Gaozong. Although she has been painted in an unfavourable light by many historians, it is often forgotten that her self-proclaimed Zhou Dynasty was nothing less than a success. She managed to maintain the prosperity of the preceding Tang Dynasty and even improved on areas where her male predecessors had failed.

During her reign, Empress Wu successfully pushed the Chinese Empire deeper into Central Asia and completed the conquest of the upper Korean Peninsula. She effectively expanded the reaches of the empire much further than it had ever been before.

In 683, she increased the importance of the imperial examination as a method for selecting officials and allowed newer members of the gentry to take it, when previously they had been disqualified due to their low class background or family name. This increased the opportunity for people in the north China plain to become government officials, whereas previously these positions usually fell to the northwestern aristocracy. In this respect she was responsible for huge social change, as she repressed the ruling aristocracy and elevated members of less wealthy or highborn families. Thus she created a new reformed upper-class directly beneath her that was fiercely loyal to her.

In a further effort to improve life for the lower classes, she changed the taxation system so that it was based on individual wealth rather than a fixed per capita levy, which reduced the amount of tax that poorer families had to pay. She also utilised the preceding Sui Dynasty’s Juntian or “Equal-Field” System to ensure fair land allocation to farmers. These edicts were known as her “Acts of Grace”, as they helped elevate members of the lower classes who previously had no hope of improving their situation. In short, she may have been a curse to the aristocracy, but she was nothing short of a blessing to the common people!

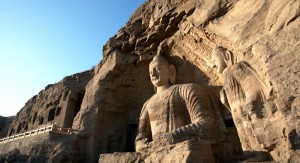

When it came to religion, she made Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching[1] required reading for all Imperial University students and elevated the status of Buddhism to be above that of Taoism, making it effectively the national religion. To this end, she patronised the construction of several Buddhist statues and grottoes.

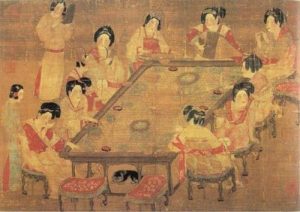

She fostered a creative atmosphere at court and encouraged mid-level officials such as Yuan Wanqing, Fan Lübing, and Miao Chuke to cultivate their literary talents. She would frequently commission them to write works on her behalf and was even known to write herself, although most of her works were of a political nature. There are forty-six of her poems collected in the Quantangshi (Collected Tang Poems) and sixty-one of her essays in the Quantangwen (Collected Tang Essays).

Her support for the literary arts led to the final development of what was known as the “new style” of poetry or “jintishi” by the poets Song Zhiwen and Shen Quanqi, which consisted of a more regulated verse than previous styles of poetry. She also took great pains to improve the situation for women in ancient China and commissioned a work known as the Collection of Biographies of Famous Women, which was designed to raise the status of women in society as a whole.

Wu Zetian fortuitously took over at a time when the people were reasonably contented, the administration was run well, and the economy was on the rise. This meant that living standards were gradually improving for everyone, even the lower classes. She succeeded in maintaining the prosperity enjoyed during the Tang Dynasty and thus was perceived, at least by the masses, to be a successful and benevolent Emperor.

However, after the year 700, she became entangled in a number of romantic affairs with sycophantic officials and began losing her grip on political matters. Her inability to quash a number of foreign invasions meant that the empire was being progressively weakened. In 705, she was finally forced to abdicate in favour of Emperor Zhongzong, who re-established the Tang Dynasty.

[1] Tao Te Ching: A classical Chinese text written by philosopher and scholar Lao Tzu. It is widely regarded as the fundamental text for the Chinese religion Taoism.

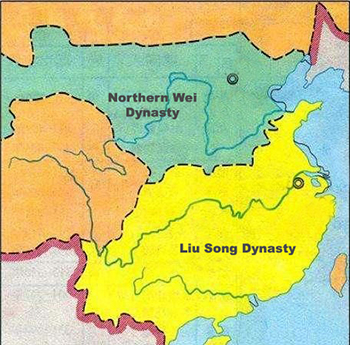

Emperor Taiwu masterminded numerous expeditions against the southern Liu Song Dynasty (420–479) but, because of harassment from the Mongol-led Rouran Khaganate (330–555) in the north, he could not focus all of his efforts on vanquishing his southern rivals. His descendants would try numerous times to succeed where he had failed, but none of them would manage to make any significant territorial gains in the south.

Emperor Taiwu masterminded numerous expeditions against the southern Liu Song Dynasty (420–479) but, because of harassment from the Mongol-led Rouran Khaganate (330–555) in the north, he could not focus all of his efforts on vanquishing his southern rivals. His descendants would try numerous times to succeed where he had failed, but none of them would manage to make any significant territorial gains in the south.