Explore the Silk Road in China – Exclusive Itinerary for December 2020

The Xumi Mountain Grottoes

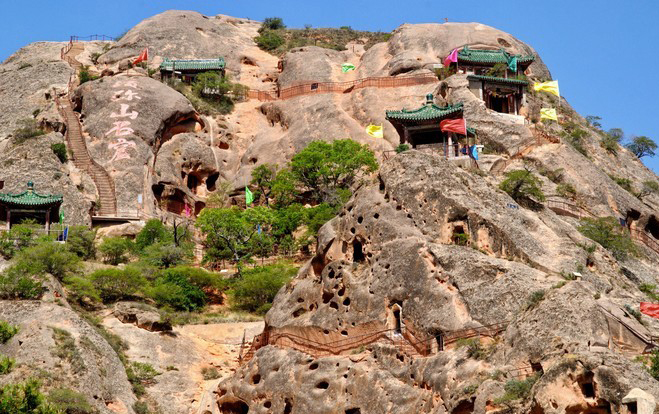

Dating all the way back to the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535), the Xumi Mountain Grottoes are classed as one of the 10 most culturally significant Buddhist grottoes in China. On the eastern edge of Mount Xumi, eight red sandstone cliffs are speckled with over 160 hand-carved caves, 70 of which contain magnificent carvings, colourful murals, spectacular frescoes, and delicate inscriptions. The site’s star attraction is a 20-metre (65 ft.) tall statue of Maitreya[1] Buddha, who looks wistfully out into the surrounding countryside. To put that into perspective, it’s about four times as tall as an adult giraffe! However, there’s more to this scenic site than just one (very) big Buddha.

Although the complex was originally built during the Northern Wei Dynasty, its construction spans five dynastic eras, as it was periodically added to right up until the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The grottoes are located along the Silk Road, which was integral to the dissemination of Buddhism in China. Their location along this trade route is palpable in the Indian and Central Asian motifs that appear in many of the sculptures and paintings. Grotto No. 33, with its square layout and partition wall punctuated by three portals, is a typical example of this, as it greatly resembles a traditional Indian temple. As time went on, the grottoes that were added and the art within them became distinctly more Chinese in style, demonstrating the gradual Sinification of Buddhism in China.

The mountain’s name, “Xumishan” or “Mount Xumi”, is actually the Chinese variation of the Sanskrit word for Mount Sumeru, the cosmic mountain that rests at the centre of the universe according to Buddhism. It was originally known as Mount Fengyi, but this spiritual rebranding was thought to be a ploy to encourage more monks to travel to the site, live there, and help carve more grottoes. Talk about false advertising! Many of the caves have virtually no decorative elements and it is believed that they were used to house the resident monks.

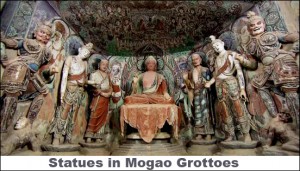

Nowadays the site has been separated into five main areas: Dafo or “Big Buddha” Tower, Zisun Palace, Yuanguang Temple, Xiangguo Temple, and Taohua Cave. Grottoes No. 45 and 46 are some of the most noteworthy, since they contain the largest number of statues, 40 of which are taller than the average person. Grotto No. 14 is believed to be the oldest and contains statues and paintings dating back to the early Northern Wei Dynasty. Though primitive in design and colour, they are resplendent in their simplistic beauty. Much of the statuary in this grotto resembles that of the famous Yungang Grottoes in Shanxi province and the Mogao Caves in Gansu province.

Unfortunately, in spite of being designated a National Level Cultural Relic Protected Site in 1982, the Xumi Mountain Grottoes are currently at risk. Wind and sand erosion, unstable rock beds, earthquakes, and vandalism have already caused irreparable damage to the caves, and a recent study suggests that only about 10 per cent of them are in decent condition. The extent of the damage has led to the grottoes being listed as one of the Top 100 Most Endangered Historical Sites in the world. So be sure to catch them while you can, or risk missing out on this treasure trove of ancient Buddhist art!

[1] Maitreya: In the Buddhist tradition, Maitreya is a bodhisattva who will appear on Earth sometime in the future and achieve complete enlightenment. He will be the successor to the present Buddha, Gautama Buddha, and is thus regarded as a sort of future Buddha.

Tianshui

Long before recorded time, it was believed that the universe consisted solely of formless chaos. Over 18,000 years, this chaos formed into a cosmic egg, which housed a sleeping giant named Pangu. When he awoke, Pangu set about creating the world. First, he separated Yin from Yang with a swing of his giant axe, creating the Earth and the Sky. In order to keep them apart, he stood upon the Earth and held up the Sky for over 18,000 years, until he tragically died. On his death, his breath became the wind, mist, and clouds; his voice became the thunder; his left eye, the sun; his right eye, the moon; his head formed the mountains; his blood flowed into rivers; and his muscles became fertile land. In short, every part of Pangu’s body formed an integral part of the world we live in, including several of the deities that are still worshipped in Chinese folklore today.

He is the focal figure of the Chinese creation myth and, from his death, a powerful being named Huaxu was born. Huaxu gave birth to two central figures in Chinese mythology: Fuxi and Nüwa. They supposedly had the faces of humans and the bodies of snakes, although they are often regarded as the first human beings. So, next time someone accuses you of being as sneaky as a snake, just say it’s in your DNA! According to legend, Fuxi was born sometime during the 29th century BC in the town of Chengji, which is usually identified as modern-day Tianshui. He ended up marrying his sister Nüwa and together they used clay to create the first human beings on earth. He then taught mankind how to hunt, fish, domesticate animals, and cook, and is even credited with developing the first Chinese writing system and establishing the institution of marriage. Not too shabby for a guy who had to slither around on his belly all day!

He is heralded as one of the Three Sovereigns, which were god-kings or demi-gods who used their powers to improve the progress of mankind. During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the Fuxi Temple was erected in Tianshui to honour this mythical ancestor and nowadays throngs of visitors still flock to the temple every year, particularly during the annual Tianshui Fuxi Culture and Tourism Festival in June. So, while many cities in China boast beautiful natural surroundings or stunning architecture, very few of them can claim to be the birthplace of a god!

Yet the city’s illustrious history doesn’t end there. Archaeological evidence suggests that the area was settled by humans as early as the Neolithic Period (c. 8500-2100 BC), making it one of the cradles of ancient Chinese civilisation. The famous Dadiwan Site in Zhangshaodian Village can be found just northeast of the city and consists of over 200 primitive houses that date back approximately 4,800 to 7,800 years ago. It is one of the most well-preserved Neolithic sites in the country and some of the houses’ even contain prehistoric paintings of humans and animals!

The name “Tianshui” literally means “Water from the Heavens” and it was a fantastical local legend that lent the area its unusual epithet. According to this legend, sometime during the Han Dynasty (206 BC– 220 AD) the region suffered from a long drought and was racked by warfare. Suddenly a colossal storm struck, with gale force winds, heavy rain, lightning and thunder only adding to the locals’ troubles. This storm was so powerful that it split the sky itself and water poured down from the heavenly realm, creating the Tianshui Lake. So, out of great tragedy and suffering, came great beauty. That being said, the city wouldn’t formally be given the name until 1950, so don’t go there with the intention of drinking some holy tap water!

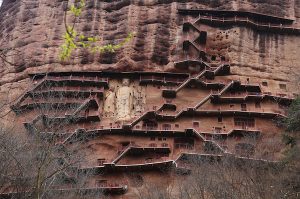

Its auspicious position meant that, during the Han Dynasty, it swiftly became one of the major trading hubs along the ancient Silk Road. Like many of the oases towns along the Silk Road, Buddhism made its way to Tianshui around about the 5th century and wonderful works of Buddhist art and architecture soon followed, including the nearby Maijishan Grottoes. Resting just 40 kilometres (25 miles) southeast of the city proper, this cave complex is renowned as one of the Four Grand Groups of Grottoes and represents 194 caves filled with over 7,200 Buddhist sculptures and 1,000 square metres (10,700 sq. ft.) of intricate murals. This colossal endeavour was begun sometime during the Northern Liang Dynasty (397–460) and continued for over 1,000 years. Even at the grand old age of over 1,500, the Maijishan Grottoes have yet to retire and still welcome visitors on a daily basis!

Its auspicious position meant that, during the Han Dynasty, it swiftly became one of the major trading hubs along the ancient Silk Road. Like many of the oases towns along the Silk Road, Buddhism made its way to Tianshui around about the 5th century and wonderful works of Buddhist art and architecture soon followed, including the nearby Maijishan Grottoes. Resting just 40 kilometres (25 miles) southeast of the city proper, this cave complex is renowned as one of the Four Grand Groups of Grottoes and represents 194 caves filled with over 7,200 Buddhist sculptures and 1,000 square metres (10,700 sq. ft.) of intricate murals. This colossal endeavour was begun sometime during the Northern Liang Dynasty (397–460) and continued for over 1,000 years. Even at the grand old age of over 1,500, the Maijishan Grottoes have yet to retire and still welcome visitors on a daily basis!

Another equally magnificent yet less well-known grotto complex can be found in the valleys of the Zhonglou Mountains just northeast of Tianshui. Amongst verdant hills, flowery meadows, and bubbling brooks you’ll find the secluded Water Curtain Cave Complex, which hides a sequence of five grottoes known as the Water Curtain Cave, Thousand Buddha Cave, Lashao Temple, Xiansheng Pond, and Sanqing Cave. These were once an important pilgrimage site along the Silk Road and date all the way back to the Jin Dynasty (265-420). During the rainy season, water cascades from the top of the mountain and covers the mouth of the cave like a curtain, earning the grotto complex its unusual name. Filled with gorgeous murals and resplendent with natural beauty, a trip to these caves is sure not to dampen your spirits!

Join a travel with us to explore more about Tianshui: Explore the Silk Road in China

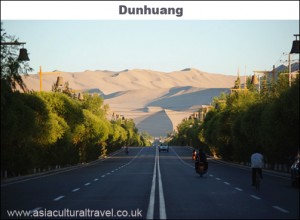

Dunhuang

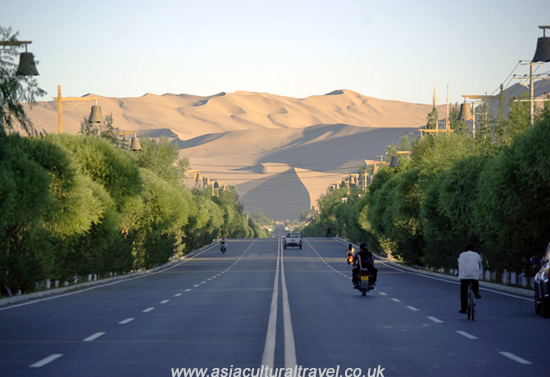

Situated at the point where the historic northern and southern branches of the Silk Road once met, Dunhuang is a city rich in cultural and historical significance. Flanked by the Gobi Desert to its east and the Mingsha or “Gurgling Sand” Dunes to its south, the city was a vital resting place for any pilgrims, traders, or travellers longing to escape the seemingly endless sandy plains. The “gurgling” sand dunes were so-named for the ghostly sound of the wind whipping over them, which perturbed Silk Road traders so much that they believed the desert to be haunted. No wonder they were eager to reach the next trading town! With the legendary Mogao Caves and shimmering Crescent Lake resting on its outskirts, Dunhuang has swiftly become a mecca for those intrigued by the history of the Silk Road.

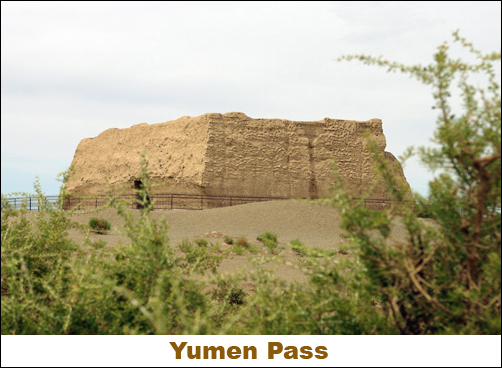

It was originally established as a garrison town during the Han Dynasty (206 BC– 220 AD) and was designed to protect the Silk Road from northern invaders. Along with Jiuquan, Zhangye, and Wuwei, it was one of the four main garrison towns established by Emperor Wu in an effort to keep control of the Hexi Corridor. The power and wealth generated by the Silk Road made it an invaluable asset to the Han court, and they were so intent on guarding it that they built long sections of wall along the northern frontier. These include the historic Yumen Pass and Yang Pass, two of the last remaining earthen portions of the Great Wall. Yet it seemed these efforts were largely in vain, as frequent conflicts meant that Dunhuang would regularly be cut off from the imperial court for long periods at a time. In its long history, the city would be controlled by the Mongolian Xiongnu people, the Turkic Tuoba, the Tibetans, the Uyghurs, and the Tanguts. In short, it changed hands more times than an unwanted Christmas jumper!

When the Han Dynasty eventually collapsed, the city became semi-independent and was allowed to flourish as a cosmopolitan metropolis, making it a veritable haven for monks, traders, and travellers from all countries and religions. Thanks to the Silk Road, Buddhism reached Dunhuang relatively early in its history and it became one of the world’s great Buddhist centres in 366 AD, nearly 80 years before the imperial court would finally recognise it as a religion. In other words, people in Dunhuang followed Buddhism before it was cool!

During this time, a Buddhist monk named Le Zun had a vision of one thousand Buddhas bathed in golden light and saw it as a divine sign that he must devote his life to carving one thousand Buddhist grottoes. Word of this spread fast along the Silk Road, and soon droves of monks arrived to help Le Zun pursue his noble dream. This sequence of artistic grottoes, which were begun in 366 and tragically abandoned during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), is now known as the Mogao Caves. Not only does it represent a treasure trove of spectacular Buddhist art, its contents also serve as proof that Dunhuang and other surrounding oasis towns once played host to a myriad of ethnicities and religions.

During this time, a Buddhist monk named Le Zun had a vision of one thousand Buddhas bathed in golden light and saw it as a divine sign that he must devote his life to carving one thousand Buddhist grottoes. Word of this spread fast along the Silk Road, and soon droves of monks arrived to help Le Zun pursue his noble dream. This sequence of artistic grottoes, which were begun in 366 and tragically abandoned during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), is now known as the Mogao Caves. Not only does it represent a treasure trove of spectacular Buddhist art, its contents also serve as proof that Dunhuang and other surrounding oasis towns once played host to a myriad of ethnicities and religions.

The library cave, a hidden compartment of the cave complex that was re-discovered in 1900, contained over 45,000 manuscripts in numerous languages, including Tibetan, Uyghur, Sanskrit, and even Hebrew. Many of them were Buddhist in content, but some of them pertained to Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Christianity, Taoism, and Judaism. Still more fascinating is that some of them weren’t even religious, but instead had belonged to merchant caravans and contained detailed descriptions of their wares. These documents indicated that silk from Persia, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, agate from India, and amber from as far away as northeast Europe had once passed through the city.

It was during the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties that Dunhuang reach its peak as a major trading hub and, by the 10th century, Buddhism had become such an integral part of its culture that there were over 15 Buddhist monasteries in the city alone. However, it fell outside Chinese borders once again during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) when it was conquered by the Tanguts of the Western Xia Dynasty (1038–1227) in 1036. It wasn’t reincorporated into China proper until the Yuan Dynasty and tragically went into a period of decline during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), when maritime trade largely overtook the Silk Road. Thus the glory days of Dunhuang were behind it and this once glorious ancient city fell into such ruin that it eventually had to be rebuilt in 1760.

Nowadays the city has become a popular tourist destination for those seeking to retrace the steps of traders following the Silk Road. And, if you really want to get to grips with the city’s mercantile roots (or should we say routes), then you’ll need to indulge in an evening spent at the Dunhuang Night Market. This lively bazaar is held in the city centre every night and hosts a plethora of fascinating products, including carved Tibetan yak horns, jade sculptures, hand-painted scrolls, ancient coins, and enough souvenirs to guarantee you’ll be checking in a second bag on your flight home!

That being said, if you fancy something a little more unusual, you’ll want to check out the Dunhuang Yardang National Geopark or, as the locals call it, the Town of Demons! This geopark rests just 185 kilometres (115 mi) outside of the city and is resplendent with bizarre geological formations known as yardangs, which are the result of extreme weathering over a period of approximately 700,000 years. One branch of the Silk Road actually passed through this strange landscape and the monstrously shaped rocks were notoriously difficult to navigate, meaning trading caravans would often get lost there for days. This, coupled with the eerie sound of the wind whipping through the narrow passes, is what earned the place its supernatural nickname!

That being said, if you fancy something a little more unusual, you’ll want to check out the Dunhuang Yardang National Geopark or, as the locals call it, the Town of Demons! This geopark rests just 185 kilometres (115 mi) outside of the city and is resplendent with bizarre geological formations known as yardangs, which are the result of extreme weathering over a period of approximately 700,000 years. One branch of the Silk Road actually passed through this strange landscape and the monstrously shaped rocks were notoriously difficult to navigate, meaning trading caravans would often get lost there for days. This, coupled with the eerie sound of the wind whipping through the narrow passes, is what earned the place its supernatural nickname!

Make your dream trip to Dunhuang come true on our travel: Explore the Silk Road in China

Xi’an

Xi’an was once one of the Four Great Ancient Capitals of China and it has managed to maintain its fine reputation to this day. It is the capital of the northern province of Shaanxi and for 13 feudal dynasties it was designated as the capital of China. Before the Ming Dynasty, it was known as Chang’an, meaning “Long-lasting Peace”, but its name was changed to Xi’an, meaning “Western Peace”, in 1369. The Lantian Man, the fossils of a human ancestor that date back over 500,000 years, were found just 50 kilometres southeast of Xi’an and Banpo Neolithic village, the remains of several Neolithic settlements that date back over 5,000 to 6,000 years, were found on the eastern outskirts of the city. Truly Xi’an must have been one of the cradles of ancient civilization.

Nowadays, Xi’an is probably most famous for being the starting point of the ancient Silk Road and for the discovery site of the Terracotta Army. Thousands of tourists flock to Xi’an every year to see the Terracotta Warriors at Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum or to start their tour of the Silk Road. With a population of just over 8 million people, Xi’an is currently the most populated city in Northwest China. Its population is growing rapidly and it is predicted it will soon become a mega-city like Beijing or Shanghai. The population of Xi’an is predominantly ethnically Han Chinese but there is a large concentration of ethnically Hui people in the Muslim Quarter of the city.

Xi’an was the first city in China to be introduced to Islam and, in 651 A.D., Emperor Gaozong of the Tang Dynasty officially allowed open practice of the religion. This allowed the Hui people, who are Muslims, to thrive in the area and thus a large concentration of them have remained in Xi’an. There are an estimated 50,000 Hui people in Xi’an and they form a tight knit community that oscillates primarily around Muslim Street and the Muslim Quarter.

Xi’an was the first city in China to be introduced to Islam and, in 651 A.D., Emperor Gaozong of the Tang Dynasty officially allowed open practice of the religion. This allowed the Hui people, who are Muslims, to thrive in the area and thus a large concentration of them have remained in Xi’an. There are an estimated 50,000 Hui people in Xi’an and they form a tight knit community that oscillates primarily around Muslim Street and the Muslim Quarter.

Xi’an is also the birthplace of the Qinqiang style of opera, which is the oldest of the four major styles of opera. It is also sometimes referred to as “random pluck” and is the main form of entertainment throughout Xi’an and Shaanxi province. If you are an avid fan of Chinese opera, you’ll notice the similarities between Qinqiang Opera and Beijing Opera, Yu Opera, Chuan Opera and Hebei Opera. This is because Qinqiang Opera is their earliest ancestor and many other styles of opera have borrowed features from the Qinqiang style. Qinqiang Opera dates all the way back to the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.) and still maintains its popularity to this day.

Aside from the Terracotta Army, the Silk Road and the wealth of cultural attractions, Xi’an is also home to several lesser known tourist attractions that are still definitely worth visiting. These include the Great Wild Goose Pagoda, Da Ci’en Temple, the Bell Tower, the Drum Tower and the Great Mosque, to name but a few. Xi’an boasts such a myriad of different architectural and cultural attractions that a lifetime may not be enough to discover them all!

Xi’an is one of the many wonderful stops on travel Explore the Silk Road in China and Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages

The Loess Plateau

The Loess Plateau, sometimes referred to as the Huangtu Plateau, is made up of terrain that is unlike anywhere else in the world. The arid, dusty countryside, covered in sparse vegetation, looks almost surreal and certainly uninhabitable. Yet locals of Shanxi and Shaanxi province have made the Loess Plateau their home for hundreds of years. It is one of the focal destinations of the Silk Road and thus its presence and history is delicately intertwined with that of China’s development. Another fact is that it serves as a wonderful destination for tourists to experience a completely alien landscape that has morphed and adapted over thousands of years.

It is called the Loess Plateau because it is an elevated plain of flat land that is covered in loess. Loess is a type of soil made up of silt and sediment that has been deposited on the plateau over time by wind storms. This type of soil is very easily eroded by water and wind, making the landscape of the plateau very unstable and changeable. The Loess Plateau itself surrounds the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River and covers an area of approximately 640,000 km². To put this into perspective, it is roughly the size of the whole of Afghanistan. This massive plateau covers parts of Shanxi Province, Shaanxi Province, Gansu Province, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and Inner Mongolia. The climate in the plateau is semi-arid, meaning the winters are cold and dry, while the summers are very warm and in many places can be very hot. The rainfall tends to be heavily concentrated in summer, bordering on monsoon-like, and the plateau receives a substantial amount of sunshine all year round.

The earliest records of this area are from people travelling along the Northern Silk Road. After the return of the explorer Zhang Qian during the first millennium BCE, the Han Dynasty began trading with the Western Regions by travelling through the southern part of the Loess Plateau, which formed part of the Northern Silk Road. They would exchange goods such as gold, rubies, jade, coral and ivory with bronze weapons, furs, ceramics and cinnamon bark.

The earliest records of this area are from people travelling along the Northern Silk Road. After the return of the explorer Zhang Qian during the first millennium BCE, the Han Dynasty began trading with the Western Regions by travelling through the southern part of the Loess Plateau, which formed part of the Northern Silk Road. They would exchange goods such as gold, rubies, jade, coral and ivory with bronze weapons, furs, ceramics and cinnamon bark.

In ancient times, the fact that the soil in the Loess Plateau was extremely fertile and easy to farm, coupled with the appearance of the Silk Road, meant that the Loess Plateau became heavily populated by farmers. These farmers took shelter in constructions known as Yaodong or Loess Cave Houses. These are houses that are carved directly into the cliff-face and are naturally air-conditioned in the summer and heated in the winter, meaning they are cheap and easy to live in. During the 1930s, the Communist Party led by Mao Zedong used several Yaodong in Yan’an as there headquarters and most Yaodong in China are still in use today.

The ancient Yaodong in the Loess Plateau are a must-see and are unlike any other building on earth. Their cultural significance dates back all the way to the Silk Road and leads right up to the Cultural Revolution. The fact that they are still used as homes today gives any visitor an insight into how people in ancient times would have lived and farmed crops or animals in the Loess Plateau. The Yaodong and the Loess Plateau act as a time-capsule that transports you back to what life was like after the establishment of the Silk Road.

Join a travel with us to discover the amazing land view of the Loess Plateau in Shanxi Province: Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages

The Silk Road in China

The term the ‘Silk Road’ was coined by a German geographer named Ferdinand von Richthofen in the 19th century. It refers to the commercial routes that connected mainland China with central Asia during ancient times. Afterwards various scholars expanded the term so that it now also applies to the routes that connected China to west Asia and even to Africa and Europe. The most common commodity exported from China was silk. However, the Silk Road was not solely used for commercial trade, but was also a point of cultural exchange between various ethnic groups in China, central Asia, west Asia, and Europe.

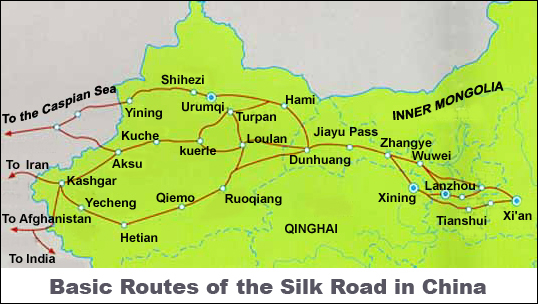

The Silk Road is in fact not only one road, but consists of several roads, so many scholars prefer to call it ‘the Silk Routes’ instead.

Generally speaking, the Silk Road can be divided into three parts – the Eastern part, the Central part, and the Western part. The Eastern and Central parts are predominantly in China, while the Western part stretches across central and west Asia and even parts of North Africa and Europe.

Routes belongs to the Silk Road in China:

The Eastern Part of the Silk Road:

The Eastern part stretches from Xi’an or Luoyang, then goes northwest through Shaanxi province and Gansu province up to Dunhuang.

Xi’an was the capital of the Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C. – 9 A.D.), while Luoyang was the capital of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25 – 220). Nowadays Xi’an is the capital of Shaanxi province, and Luoyang is just a city in Henan province.

Dunhuang is in Gansu Province. It is one of the most famous attractions in China because of its fantastic Grottoes.

The road in the Eastern part was split into three routes when it reached Gansu province – the Northern Way, the Southern Way and the Central Way.

The Northern Way: This went from Jingchuan (in Gansu Province), through Guyuan (in Ningxia Province) and Jingyuan (in Gansu Province), and ended in Wuwei (in Gansu Province). It was the shortest of the three routes, but it needed to be short as it ran through the Gobi desert, which had few water sources.

The Southern Way: This went from Fengxiang (in Shaanxi Province), through Tianshui (in Gansu Province), Longxi (in Gansu Province), Linxia (in Gansu Province), Ledu (in Qinghai Province), Xining (in Qinghai Province), and finally ended in Zhangye (in Gansu Province). This road was famously known as ‘the Hexi Corridor’. It followed the Yellow River. It was easier to traverse than the other three routes but it was also much longer.

The Central Way: This went from Jingchuan (in Gansu Province), through Pingliang (in Gansu Province), Huining (in Gansu Province), Lanzhou (in Gansu Province), and ended in Wuwei (in Gansu Province). This route was the most popular because it was not too long and not too difficult to follow.

The Central Part of the Silk Road:

The road in the Central part was also separated into three routes. The routes in this part went from Dunhuang or Anxi (named Guazhou in ancient times) in Gansu Province, but from then on mostly went through Xinjiang province, particularly through the Tarim basin. All of the routes were frequently changed according to the appearance and disappearance of oases, which were the only water source along the desert tracts.

The Northern Way: This went from Anxi, through Kumul (in Xinjiang Province), Jimsar (named Tingzhou in ancient times, now in Xinjiang Province), Ili (in Xinjiang Province), and ended in Suyab (in Kyrgyzstan).

The Southern Way: This went from Dunhuang (or the Yumen Pass, or the Yang Pass), followed the southern edge of the Taklimakan desert, then went through Shanshan (in Xinjiang Province), Hotan (named Khotan in the ancient times, now in Xinjiang Province), Yarkant (in Xinjiang Province), and ended in the Pamir Mountains.

There were several important towns on this route, such as Qaran and Niya (the capital of the Jingjue Kingdom in ancient times). All of these towns have since disappeared because of the changing desert.

The Central Way: This went from the Yumen Pass (in Gansu Province), followed the northern edge of the Taklimakan desert, then went through Lop Nur (where the Loulan Kingdom was situated in ancient times), Turpan (once part of the Cheshi Kingdom and the Gaocheng Kingdom, now in Xinjiang Province), YanQi (in Xinjiang Province), Kuqa (capital of the Kuqa Kingdom in ancient times, now in Xinjiang province), Aksu (part of the Gumo Kingdom in ancient times, now in Xinjiang Province), Kashgar (in Xinjiang Province), and ended in the Fergana Valley (once part of the Dayuan Kingdom, now in Uzbekistan).

There were several important ancient Kingdoms and large towns on this route. However, nowadays most of these towns are just ruins in the desert or have disappeared entirely.

The History of the Silk Road

In ancient China, during the Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C. – 9 A.D.), the northern frontier of the Han people was often subjected to assault by the nomadic Xiongnu tribe. Xiongnu men were notoriously good at fighting. Since this nomadic group was causing so much damage, the Han Empire decided to proffer peace by sending them treasures and arranging marriages between Xiongnu people and members of the Han royal family. The Han Empire sent their princesses to wed Khans’ (leaders) of the Xiongnu people. In fact, these women were not real princesses but were actually just girls that served the Han emperors in the palace.

In 140 B.C. Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty ascended the throne. The power of the Han Empire had grown significantly by that time. Thus Emperor Wu was able to pursue a proactive foreign policy and set a goal to defeat the Xiongnu people.

Having learned that the Xiongnu people had killed the leader of the Dayuezhi Kingdom (located in the Western Regions1) and forced its citizens to leave their land, Emperor Wu planned to form an alliance with the citizens of Dayuezhi and attack the Xiongnu.

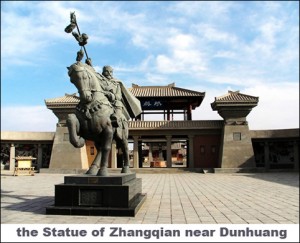

In order to implement this plan, in 138 B.C. Emperor Wu dispatched an envoy named Zhang Qian to the Western Regions. Leading more than a hundred men, Zhang Qian set off from Longxi (present-day Lintao in Gansu province). Unfortunately, on their journey they were captured by the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu forced Zhang Qian into exile in the grassland, where he stayed for more than a decade. Zhang Qian finally found an opportunity to escape and he continued his journey to the West. When he eventually arrived at Dayuezhi, he learned that its citizens had settled down in the Amu River basin and enjoyed their peaceful life there. They did not want to start a war with the Xiongnu.

Having failed to lobby an alliance between the citizens of Dayuezhi and the Han Empire, Zhang Qian embarked on his return journey. He was once again unexpectedly detained by the Xiongnu. However, this time he escaped after just one year.

In 126 B.C. Zhang Qian returned to Chang’an (present-day Xi’an in Shaanxi province), thirteen years after he had left.

Zhang Qian reported to Emperor Wu about what he had seen and heard in the Western Regions.

Emperor Wu was enthralled by Zhang Qian’s descriptions of foreign lands, exotic and tantalizing delicacies, precious stones of the brightest hue, local craftworks of the finest quality and many other things that Han people such as Emperor Wu had never heard of or seen before. Emperor Wu was so overwhelmed by these stories that he became fascinated with the Western Regions and their potential resources. So he decided to establish friendly ties with the people there.

In 119 B.C. Zhang Qian was dispatched to the Western Regions once again. He led a contingent of more than three hundred men and together they transported large quantities of gold, silk, cattle and sheep. Zhang Qian was incredibly lucky to have avoided the Xiongnu on this occasion. First they arrived in Wusu, which used to be to the southeast of Lake Balkhash. Wusu was an important hub in the Western Regions. Zhang Qian then sent his deputies to countries such as Dayuan, Kangju (present-day southeast Kazakhstan), Daxia (some scholars believed this became part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom), the Parthian Empire (present-day northeast Iran), and Sindhu (ancient India), where they were welcomed and where they conducted large-scale exchanges. In 115 B.C. Zhang Qian returned to Chang’an. Dayuan, the Parthian Empire and some other regimes in the Western Regions all sent envoys to travel with him.

Zhang Qian opened the transportation routes between the east and west parts of the Asian mainland. From 104 B.C to 101 B.C., the Han Empire set up four counties (‘jun’ in Chinese) in the Western Regions: Jiuquan, Zhangye, Wuwei and Dunhuang (all in modern-day Gansu Province). They formally incorporated these counties into the Han Empire and thus made them Han territory. Thereafter, Han envoys and merchants constantly travelled to the Western Regions to carry out political and commercial activities, while caravans from the Western Regions travelled to central China for the same reasons. Large quantities of Chinese silk were shipped to Central Asia, West Asia and even Europe via these routes.

The Western Regions: In ancient times, Han people used this term to refer to places outside of the Yumen Pass in the west. Historically there were 36 Kingdoms recorded to have belonged to the Western Regions and they were all located in modern-day Xinjiang Province and Central Asia.

The Turmoil Surrounding the Silk Road

In 8 A.D. the Han Dynasty was faced with crisis. An official named Wang Mang tried to steal the throne and managed to succeed. He established the short-lived Xin Dynasty, in which he was the first and only emperor. 17 years after his ascension to the throne, the royal Han family waged war against Wang Mang and managed to reclaim the throne. To differentiate between these two Han Empires (the one before and the one after the Xin Dynasty), we call the first one the Western Han Dynasty and the second one the Eastern Han Dynasty (25 – 220 A.D.). They are so-called because the capital of the Western Han Dynasty was Chang’an, which is to the west, while the capital of the Eastern Han Dynasty was Luoyang, which is to the east.

The Silk Road had been busy since it was built during the Western Han Dynasty. However, because of the chaos caused by the civil war, the imperial court had paid less attention to governing the Western Regions. The Xiongnu seized this opportunity to fight back against the Han Empire and thus traffic on the Silk Road was interrupted.

From 58 to 75 A.D., the Han Empire recovered from the civil war and managed to re-establish its national influence. In 72 A.D., Emperor Ming of the Eastern Han Dynasty ordered his General, Dou Gu, to travel to the Western Regions and broker an alliance that would help them defend against the Xiongnu. At the same time, the Xiongnu also made efforts to absorb these small countries into their empire. However, after several armed conflicts, the Han Empire finally succeeded.

In 97 A.D., a Han envoy named Gan Ying set off from Kuqa to visit the Seleucid Empire (present-day Iraq), the Parthian Empire and a few other countries. In 166 A.D., the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus sent an envoy to the Eastern Han Empire and thus opened up friendly exchanges between China and some of the European countries.

During the Three Kingdom Period (220-280 A.D.), the Silk Road was extended west from the Pamir Mountains onwards. A new route was opened up along the northern foot of Mt. Tianshan. This new route was the rough beginnings of the Northern Way in the Central part of the Silk Road.

Due to the frequent wars and long-term political division during what is known as the Wei Jin and the Southern and Northern Dynasty period (220-589 A.D.), the imperial court’s ability to manage the Western Regions and operate along the Silk Road was adversely affected. However, the Silk Road was not interrupted and some routes even prospered during these tumultuous times. Not to mention that the dissemination of Buddhism to the east attracted a large number of monks from India and Central Asia to China, who brought with them their spiritual knowledge and rich Buddhist culture.

The Sui and the Tang Dynasties (581-907 A.D.) finally entered into a period of socio-economic and cultural development and prosperity after this long period of social and political discord. Their national influence was unprecedentedly powerful at this time. The imperial court established stronger contacts and exchanges with the Western Regions, and thus maintained the smooth flow of traffic on the Silk Road. In 630 A.D., the Tang army defeated the Eastern Turkic regime, which had previously occupied part of the Silk Road, and strengthened the imperial court’s friendly ties with the Western Turkic regime. Later on the Tang army once again claimed total authority over the Western Regions (modern-day Xinjiang) and, in 640 A.D., the imperial court of the Tang Dynasty set up a military administration there.

The powerful Tang Empire also unified the Mobei region (places in modern-day Inner Mongolia and Mongolia). This meant a channel of communication was opened up between the Western Regions and the northern frontier. At the same time, in addition to the main routes, many new sub-routes of the Silk Road were also opened up.

The Silk Road flourished during the early years of the Tang Dynasty and formally entered its golden period. Yet midway through the Tang Dynasty, with the increase of established sea routes, more and more western merchants were coming to China by boat. The Silk Road gradually began to decline. In 755 A.D. a local military official named An Lushan launched an armed rebellion against the Tang Dynasty. Most of the Tang army stationed in the Western Regions was called back to Chang’an to safeguard the emperor. The Tibetan Empire, seizing their chance while the northwest frontier was unguarded, occupied the Helong area (west of modern-day Gansu Province), and the Uighurs, in a similar bid, took control of the Altay Prefecture (west of modern-day Xinjiang). This caused the Tang Empire to lose control of the Western Regions and the Silk Road was interrupted once again.

During the Northern Song Dynasty (960 – 1127), the Han regime was weak and controlled a limited area. Its capacity to trade with the Western Regions and foreign countries was also impeded. The Silk Road was, in a sense, practically closed. By the time the Southern Song Dynasty (1127 – 1279) began, as a result of vigorous support from the imperial court coupled with advances in shipbuilding technology, sea routes became the major channel for China’s external communication and trade. This meant that the Silk Road was almost completely abandoned.

In the 13th century, the Mongolian Empire rose to power in the northern grasslands. Having conquered the kingdoms of West Xia, Jin, and the Southern Song Dynasty, they unified China and established the Yuan Empire (1271 – 1368). The Yuan imperial court set up a pothouse system (a system of pubs or inns that were set up along the road by the imperial court) which enabled the Silk Road to flourish once again.

In 1391, the Emperor Taizu of the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644) sent an army to capture Kumul. In 1406, the Emperor Chengzu of the Ming Dynasty established an administrative office in Kumul as a base for implementing his economic policies in the Western Regions. But the Ming Empire didn’t hold power in the Western Regions for long. In 1472, a Mongolian leader named Chagatai Khan led his army to attack and eventually capture Kumul. The Ming army was forced to retreat to the Jiayuguan Pass (in Gansu Province), leaving the regions beyond the Jiayuguan Pass in political and social chaos. Although local trade among the civilian population still travelled along the Silk Road, the prosperity that the Silk Road had enjoyed no longer existed.

In the 15th century, due to the Ottoman Empire’s occupation of Constantinople (the capital city of the Eastern Roman Empire), the established trade routes between Europe and China became much more treacherous. More and more Europeans attempted to travel to the Far East by sea instead. In 1498, D. Gama discovered the Indian Ocean trade route, and thus a new channel for trade was opened between the East and the West. Meanwhile the Silk Road was gradually fading away and becoming a relic of its former glory.

Cultural and Technological Exchange on the Silk Road

The prosperity of the Silk Road facilitated the dissemination of advanced technologies and cultural features of ancient China to countries in the Western Regions, and even went as far as Central Asia, Europe and Africa. It also introduced China to technology, art and culture from various western countries.

Westward Dissemination of Chinese Culture and Technology:

Sericulture and Silk Weaving Technology

Among the commodities exported to the West via the Silk Road, silk was naturally the most famous.

In the book The Buddhist Records of the Western World by Xuanzang1, there is a historical record of how sericulture spread to the West. It states that around about 420 to 440 A.D., when the Silk Road was re-opened, the king of the Qusadanna Kingdom (located in present-day Khotan in Xinjiang) was so impressed by the elegance and beauty of the silk from ancient China that he sent his envoy to China to buy silkworm eggs and mulberry seeds. His request was not only immediately refused, but also alerted the imperial court, which had recently intensified its interrogation and examination of people who crossed the border in order to prevent the export of mulberry seeds and silkworm eggs. Later on, the king of Qusadanna proposed to one of the Han princesses, and hinted that she should smuggle silkworm eggs and mulberry seeds to him after they were wed. The princess secretly hid some silkworm eggs in her hair and also brought with her some women who were particularly skilled in the art of sericulture and silk weaving. They then built a city, named “Deer-shooting” in English, where they taught local women to grow mulberry trees and raise silkworms. Not long thereafter, the country was full of mulberry trees. Sericulture and silk reeling was quickly popularized and mastered by many of the locals. According to archaeological findings, remains of ancient mulberry trees have been unearthed both in the sand sea of Lop Nur and the ruins of the ancient Shanshan Kingdom. It was confirmed that these ancient mulberry trees were planted before the 4th century, which just about coincides with the time that the mulberry seeds and silkworm eggs were allegedly smuggled into the West.

According to the Roman historian Procopius, Chinese sericulture was introduced to the Eastern Roman Empire around 550 A.D.

During the 7th century, West Asia was occupied by the Arab Empire. In 751, a battle broke out between the Arab army and the Tang army in the Talas River area of present-day Kazakhstan. The Tang army was defeated and some silk weavers and paper workers among the Tang soldiers were captured. It is possible that this was how the Chinese arts of silk weaving and papermaking made their way to West Asia.

Tea

As a specialty of central China, tea was only produced in the areas surrounding the Yangzi River and the Huai River, and some areas in the south of China. Tea found its way into the Western Regions some time during the Tang Dynasty. In the 8th year of the Wude Period of Emperor Gaozu’s reign (625 A.D.), ethnic minorities from the Northwest, such as the Turkic people and the Tuyuhun people, attempted to promote mutual trade with the Han ethnic group. The Tang Dynasty approved of their request to trade and offered up products made from the finest silk and quality tea as their major commodities when trading with these minorities.

During the rise of the Mongolian Empire in the 13th century, tea was a luxury item available only to Mongolian aristocrats. It was not until the 14th century that tea became a popular drink for ordinary Mongolian citizens and subsequently spread to areas beyond the Western Regions. During the Ming Dynasty, the imperial court established a government-run Tea-Horse Trading System and set up Tea-Horse Agencies in Gansu and Sichuan whose job it was to govern the tea trade. The imperial court aimed to exert control over ethnic minorities in the Western Regions by regulating the Tea-Horse Trade. Tea-drinking culture had already become a staple part of the daily life of ethnic minorities in the Western Regions. Its influence had even spread to Central Asia.

Note: There is a “second Silk Road” in the south of China, which is named the Ancient Tea-Horse Road. This road was established more than a thousand years ago for trade between Yunnan, Sichuan and Tibet. The major commodities traded on this route were tea and horses.

Apart from silk and tea, many scholars believe that the technology behind papermaking, paper printing and gunpowder production also disseminated from China to the western world via the Silk Road.

Eastward Dissemination of Foreign Culture and Technology:

Buddhism

Buddhism entered the Western Regions around 60 A.D. from Gandhāra. Knowledge of the religion then spread through the Yumen Pass and the Hexi Corridor and penetrated into inland parts of China. Gradually it spread throughout the whole country.

Thanks to the eastward dissemination of Buddhism, various styles and works of art, such as grottoes, sculptures, and mural paintings, also made their way into China. These styles were then integrated with more traditional Chinese art-styles and a large volume of Buddhist sculptures and mural paintings were produced in China. The most famous of these are the Grottoes at Dunhuang, Maijishan, Yungang and Longmen. There are also many less famous Grottoes in Xinjiang province.

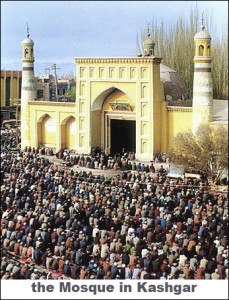

Islamism

Islam was first introduced in China during the Tang Dynasty when a large number of Muslim merchants came from West Asia to trade in China. During the 10th century, Satuk Bugera Khan, King of the Karahan Empire based in Kashgar and Artux, converted to Islam. In the early 11th century, the Karahan army conquered the Khotan Kingdom and changed the official local religion to Islam, converting many of the local people in the process. By the 13th century, along with the large-scale expedition of the Mongolian armed forces, a large number of Persians and Arabs who followed Islam came to China and mixed with the locals, gradually forming a unique Chinese Muslim community.

Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism from Persia and Nestorianism from East Rome also made their way into China. All of these religions entered China via the Silk Road during the Tang Dynasty.

Sugar Processing

China began growing sugar cane during the “Spring and Autumn and the Warring States Period” (770 B.C. – 221 B.C.). However, Chinese people only ever chewed the raw canes or extracted juice from them. According to historical records, the technology for sucrose brewing had appeared in India as early as the Western Han Dynasty (in China). While trading on the Silk Road, Han people saw the end-product (the refined sugar) being sold and wanted to learn how to make it themselves.

Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty sent an envoy to ancient India to study the technology behind sugar-refinement.

Glass

The common opinion is that Sumerians living in Mesopotamia invented glass around about 5000 B.C. By 2000 B.C. Phoenicians living on the west coast of modern-day Lebanon and Syria had passed this method of making glass on to the ancient Egyptians, who then improved and perfected the method. As early as 1000 B.C. glass was introduced into the Western Regions in Xinjiang. With the establishment of the Silk Road in the 5th century, the technology of glass-manufacture was finally introduced in China by Dayuezhi traders from Central Asia.

Cotton

More than several dozen species of plant were introduced into China via the Silk Road, including grapes, cucumber, walnuts and garlic. In particular the introduction of cotton had a far-reaching impact on China’s economic development and Chinese people’s livelihoods.

Cotton was originally grown in India and Africa. The Xinjiang region in China was the first place in the country that started growing cotton. By the Eastern Han Dynasty, Xinjiang was already engaged in growing cotton, spinning cotton wool and weaving cotton fabrics.

Before cotton was introduced into China, Chinese clothing was predominantly made of fur, silk and linen. During the Tang Dynasty, the Tang troops conquered Gaochang (in the Tarim basin) and brought back cotton seeds to grow further inland. By the Yuan Dynasty, cotton had become the main material used to make clothing in China.

No matter which direction they were going in, plenty of products and technologies made their way to different ethnic groups thanks to the Silk Road. All of these groups benefited a lot from the different arts and technologies they were exposed to.

Xuanzang(602 – 664), a Chinese Buddhist monk and scholar, who mainly studied and focused his efforts upon the interaction between China and India during the Tang Dynasty.

Major Cities along the Silk Road

In China, the Silk Road passes through three provinces – Shaanxi, Gansu and Xinjiang. There are many big cities and towns in these provinces. Most of them still play an important role in China today.

Xi’an

The Silk Road begins in the ancient capital city of Chang’an, which is now known as Xi’an. As early as the Palaeolithic Age the original settlers thrived in the area around Xi’an, leaving many historical remains, such as the Site of the Lantian Man. During the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th century B.C. – 771 B.C.), the capital city of Haojing was located in the northwest part of Xi’an. When the Western Han Dynasty was established, the imperial court chose Chang’an as its capital city. From then one, for more than a thousand years, Chang’an was the capital city and served as the capital of twenty-one different dynasties. Among these dynasties, the Han Dynasty, the Sui Dynasty and the Tang Dynasty were known to be very powerful and prosperous regimes in Chinese history.

The Silk Road begins in the ancient capital city of Chang’an, which is now known as Xi’an. As early as the Palaeolithic Age the original settlers thrived in the area around Xi’an, leaving many historical remains, such as the Site of the Lantian Man. During the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th century B.C. – 771 B.C.), the capital city of Haojing was located in the northwest part of Xi’an. When the Western Han Dynasty was established, the imperial court chose Chang’an as its capital city. From then one, for more than a thousand years, Chang’an was the capital city and served as the capital of twenty-one different dynasties. Among these dynasties, the Han Dynasty, the Sui Dynasty and the Tang Dynasty were known to be very powerful and prosperous regimes in Chinese history.

When the Silk Road was first opened during the reign of Emperor Wu of the Western Han Dynasty, Chang’an became larger and richer. It covered an area of about thirty-six square kilometres and had twelve gates and eight major streets. At the time, the city was four times the size of the capital city of Rome. Export goods, such as raw silk, satin and leather from all over the country, were first shipped to Chang’an. There they were wrapped and packed with painted linen and leather into bundles by foreign merchants, then shipped out on huge foreign caravans to westbound cities on the Silk Road.

During the Tang Dynasty, Chang’an enjoyed the period of greatest economic prosperity in its history. The whole city was 2.4 times larger than it had been during the Han Dynasty. The city’s layout was like a chessboard, and the imperial palace was surrounded by rings of outer city walls. The uniform residential buildings and the efficient water supply network reflected how advanced society in this city had become. During that time, Chang’an truly deserved the honour of being called an international metropolis. According to historical records, over three hundred countries and regions sent envoys to Chang’an to establish diplomatic connections.

When Buddhism was first introduced into mainland China, many Buddhist temples were built in Chang’an. At around about the same time, a few Muslim mosques were also erected in the city.

Tianshui

Located in the southeast of Gansu Province, Tianshui was known as Qinzhou in ancient times. When Emperor Yingzheng, the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty (221 B.C. – 207 B.C.), unified China in 221 B.C., Qinzhou was officially established as an administrative unit. In 114 B.C., during the Western Han Dynasty, the Emperor Wu set Tianshui up as a county.

Thanks to the opening of the Silk Road, Tianshui became one of the major towns for trade. Not only that, it also kept many precious records of the eastward spread of foreign cultures coming into China. For example, the famous Maijishan Grottoes, which are sometimes known collectively as the “Oriental Sculpture Museum”, are in Tianshui.

As one of the four major groups of grottoes in China, the Maijishan Grottoes have more than 1600 years of history behind them. The digging of the caves started during the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420 – 589 A.D.). Now the Maijishan Grottoes boast ownership of one hundred and ninety-four caves with more than seven thousand two hundred stone statues and one thousand three hundred square metres of mural paintings in them.

As one of the four major groups of grottoes in China, the Maijishan Grottoes have more than 1600 years of history behind them. The digging of the caves started during the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420 – 589 A.D.). Now the Maijishan Grottoes boast ownership of one hundred and ninety-four caves with more than seven thousand two hundred stone statues and one thousand three hundred square metres of mural paintings in them.

Apart from the Maijishan Grottoes, there are also many other similar grottoes in China. For example, there are grottoes in the Huagai Temple, the Gangu valley, the Wooden Ladder Temple and the Meditation Temple. All of these grottoes make up the Hexi Corridor or the “Grotto Corridor” on the Silk Road.

Wuwei

Wuwei is located in the middle of Gansu Province. It belonged to the Dayuezhi Kingdom two thousand years ago. During the early Western Han Dynasty, the Xiongnu defeated the Dayuezhi and occupied this area. In 121 B.C. Emperor Wu sent his favourite General, named Huo Qubing, to fight against the Xiongnu and was rewarded with a colossal victory. The entire Hexi Corridor was incorporated into the territory of the Western Han Dynasty. Later on, four administrative counties were set up there – Wuwei, Jiuquan, Zhangye and Dunhuang.

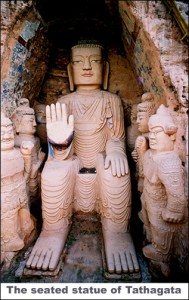

Located in the south of Wuwei city, the Tiantishan Grotto (also known as the Temple of the Giant Buddha) was built by the late Liang administration when the Sixteen Kingdoms ruled in succession in the North of China alongside the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317 – 420 A.D.).

The seated statue of the Tathagata Buddha is in the main structure known as the “Giant Buddha Cave”. It has been so meticulously carved that its vivid facial expression makes it seem almost like it’s alive.

Zhangye

Zhangye is located in the northwest of Gansu Province. In 121 B.C., during the Western Han Dynasty, Zhangye was set up as a county. The name meant “the Han Court’s arms open to link up with the Western Regions”. After it was established as a county, the imperial court implemented a large scale immigration and land reclamation program in Zhangye. They stationed their troops there and helped develop local agriculture.

During the Wei and Jin periods, Juqu Mengxun, a military commander of the Xiongnu ethnic group, established the Northern Liang Kingdom (397or401 – 439) and designated Zhangye as its capital. He supported Confucianism and expanded exchanges with the Western Regions. He also promoted Buddhism and authorized the building of many grottoes.

During the Wei and Jin periods, Juqu Mengxun, a military commander of the Xiongnu ethnic group, established the Northern Liang Kingdom (397or401 – 439) and designated Zhangye as its capital. He supported Confucianism and expanded exchanges with the Western Regions. He also promoted Buddhism and authorized the building of many grottoes.

During the Northern Song Dynasty (960 – 1127), the Dangxiang ethnic group established the Western Xia Kingdom (1038 – 1227) and built a large Buddhist temple named the Big Buddha Temple. There is a Shakyamuni Nirvana reclining statue here which has a wooden base and is made of clay that has been painted gold. It is the largest reclining Buddha statue in the world.

Dunhuang

The name Dunhuang was adopted during the Western Han Dynasty and it means “large and prosperous”. Since its official incorporation as a county in 111 B.C., Dunhuang has been habitually regarded as the border between Han territory and the Western Regions. Since it was the most important transportation hub on the Silk Road, Dunhuang became a large commercial trade town. During the Tianbao Period (742 – 756) of the Tang Dynasty, the population of Dunhuang increased to approximately one hundred and twenty thousand.

Dunhuang is also well known for its Buddhist Grottoes. There are three grotto sites in Dunhuang – the Mogao Grottoes (Thousand Buddha Caves), the Yulin Grottoes (Ten Thousand Buddha Valley) and the West Thousand Buddha Caves. The Mogao Grottoes are the most famous and were listed as a world heritage site by UNESCO in 1987.

Turpan

Lying in the Tarim basin to the east of the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang Province, Turpan has been the transportation hub linking mainland China to central Asia, as well as southern Xinjiang to northern Xinjiang, since ancient times. It naturally became an important town along the Silk Road.

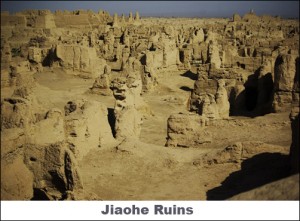

During the Western Han Dynasty, Turpan was controlled by the former Gushi Kingdom. Between 99 B.C. and 72 B.C., wars frequently broke out between the Western Han people and the Xiongnu people, who were competing for control of the Western Regions. When the Xiongnu ultimately failed, the Gushi Kingdom surrendered to the Han Dynasty and was formally incorporated into the Western Han’s territory. The Western Han Dynasty divided the former Gushi territory into eight counties and ruled them all separately. The former Gushi citizens were allocated a place in the Turpan Basin, with Jiaohe as their capital city.

Jioahe was built on a large island in the middle of a river. This formed a natural moat around the city that helped to defend it. There were steep cliffs on all sides of the river. The city was abandoned in the 13th century, and the river has long since dried up and has been gone for hundreds of years.

During the Early Liang Period (320-376 A.D.), Gaochang County was set up in the Turpan region. During the Northern Wei Period (386-534 A.D.), the Rouran ethnic people established the Gaochang Kingdom. In 450 A.D., after the former Gushi Kingdom was eliminated by the Northern Liang Dynasty, Gaochang city became the political, economic and cultural centre of the Turpan Basin. In 640 A.D., the Tang Dynasty unified the Turpan area once again and Gaochang was changed into a county of the Tang imperial court.

The surviving Gaochang ruins were built when it was ruled by the Uighurs but were constructed on the bases of the original Tang structures. There are many cultural relics in this city, such as the Manichaean mural paintings, the documents from the Uighur period and the Buddhist murals, statues and documents, all of them in different languages.

The Turpan region is also one of the epicentres of Uygur culture. Ancestors of the modern-day Uygur ethnic minority were ancient Uighurs, who entered the Western Regions during the 9th century and settled down in Turpan. The Uygur culture has its own uniquely charming styles of art, including their own styles of music, dance, costumes, rituals and architecture.

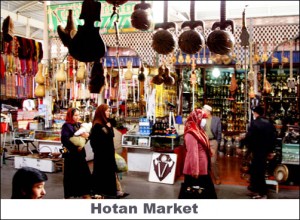

Hotan

Hotan, sometimes referred to as Hetian, is in the south of Xinjiang Province, on the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert. Hotan was one of the first areas where Buddhism was introduced in China. As early as the 1st century B.C. Buddhism was introduced in Khotan (Hotan’s ancient name) and it subsequently became the first centre of Buddhist culture in the Western Regions. Khotan was known back then as “Khotan the Buddhist Kingdom”. However, with the eastward dissemination of Islam in the 11th century, people in the Khotan region gradually converted to Islam instead.

As an important town on the Silk Road, Hotan was one of the first sericulture and silk production centres in Xinjiang. With fertile land and adequate sunshine, the climate in Hotan was well-suited for growing and producing silk.

The most famous specialty commodity from Hotan was and still is jade. As early as the Neolithic Period, Hotan locals mined jade in Mt. Kunlun. The trade route from Hotan used for transporting jade was established 1000 years before the Silk Road even existed. This route was named the Jade Road and is often considered the predecessor of the Silk Road.

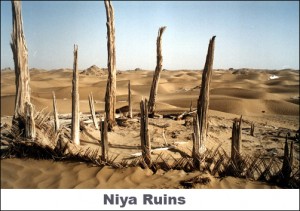

Located in the Taklimakan Desert, one hundred and fifty kilometres north of Hotan, you’ll find the famous Niya Ruins. The Niya Ruins were first discovered in 1901 by Marc Aurel Stein, a Hungarian archaeologist who had British citizenship. However, at the time he was unable to identify the ruins and it wasn’t until the 1930s that they were finally identified as the former capital city of the Jingjue Kingdom.

Kashgar

Kashgar sits on the southwest edge of Xinjiang and is China’s westernmost city. Many different regimes have controlled Kashgar at different points in its history. During the Tang Dynasty, Kashgar became an important military stronghold for the Tang imperial court. After the Tang Dynasty, Kashgar was ruled by the Karahan Empire (840-1212) and the West Liao Kingdom (1124-1218) successively. During Genghis Khan’s successful expedition westward, he conquered Kashgar and made it is his second son’s fiefdom.

From the Han Dynasty onwards, the southern, northern and central parts of the Silk Road all passed through Kashgar. Kashgar was the main distribution centre and the largest transport hub on the Silk Road. Its location and history heavily influenced the development of Kashgar’s unique layout and style. The city looks like a combination of an ancient city from central Asia and west Asia. The old parts of Kashgar are the only surviving districts in China that show what cities in the ancient Western Regions would have looked like.

Enjoy the magnificent landscape and discover more culture along the Silk road on our travel: Explore the Silk Road in China