The city of Turpan, also known as Turfan, lies about 180 kilometres (112 mi) southeast of the regional capital of Ürümqi, on the northern edge of the deep Turpan Depression. The Bogda Mountains, an eastern extension of the Tian Shan Mountains, rest to the north, while Qoltag Mountain rises to the south. Its unusual location means its climate is pretty unique, with long hot summers and cold brief winters.

The city of Turpan, also known as Turfan, lies about 180 kilometres (112 mi) southeast of the regional capital of Ürümqi, on the northern edge of the deep Turpan Depression. The Bogda Mountains, an eastern extension of the Tian Shan Mountains, rest to the north, while Qoltag Mountain rises to the south. Its unusual location means its climate is pretty unique, with long hot summers and cold brief winters.

On average, temperatures can range from −7 °C (18 °F) in January to 32 °C (90 °F) in July, but extremes of an icy cold −28 °C (−20 °F) in winter and a swelteringly hot 48 °C (119 °F) in summer are surprisingly common. The long hours of sunshine and characteristic dry heat have earned Turpan the grand title of the “Flaming Continent”. So skip the tanning beds, because you won’t be needing them in this sunny city!

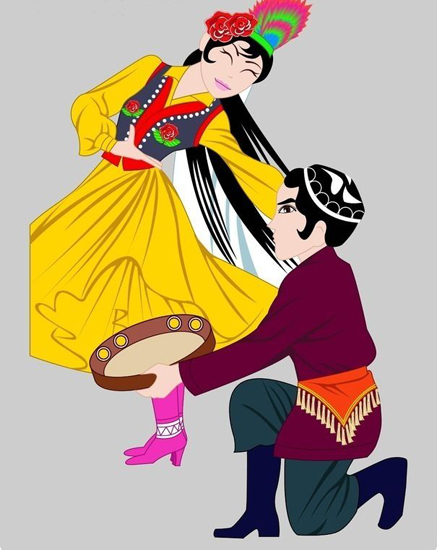

The city’s 570,000-strong-population appear to take the heat in their stride, and most of them belong to the Uyghur ethnic minority. In fact, though at a glance the terrain may appear to be harsh and unforgiving, Turpan actually rests at the centre of a fertile oasis and was once an important trade centre along the northern branch of the Silk Road. Proof that you should never judge a book by its cover, or a city by its weather!

Historically speaking, the area surrounding Turpan has been inhabited for over two thousand years. Originally, during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), it belonged to the Gushi Kingdom, later to be known as the Jushi and Cheshi Kingdom. The capital of the Cheshi Kingdom, a city known as Jiaohe, came under the control of the Han court during the 1st century, but the entire region was eventually annexed by the Gaochang Kingdom during the 6th century.

In 640, during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the region was conquered by Emperor Taizong and Turpan became one of China’s frontier towns, flourishing as a stopover for merchants, monks, and other travellers on their way to the west. By the 13th century, the region had come under Mongolian control and Turpan enjoyed its greatest period of commercial prosperity. Yet the higher you go, unfortunately the further you have to fall!

Tragically, when Mongol rule collapsed, the Turpan Depression was divided into three independent states and the area wasn’t properly united until the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). During this recovery period, Turpan suffered greatly during the wars between the Qing imperials and the resident Dzungar people. During the 18th century, a new city known as Guang’an was built next to the old Muslim city of Turpan and this eventually became the site of modern-day Turpan.

Nowadays the abundant sunshine and high temperatures in the city mean that it’s the ideal place for growing several types of fruit, particularly grapes and melons. The Grape Valley is just 11 kilometres (7 mi) northeast of Turpan and has produced the best grapes in the country for over 1,000 years, earning it the nickname “Green Pearl City”. It boasts over 13 varieties of grape, which visitors are welcome to admire and, occasionally, sample!

Nowadays the abundant sunshine and high temperatures in the city mean that it’s the ideal place for growing several types of fruit, particularly grapes and melons. The Grape Valley is just 11 kilometres (7 mi) northeast of Turpan and has produced the best grapes in the country for over 1,000 years, earning it the nickname “Green Pearl City”. It boasts over 13 varieties of grape, which visitors are welcome to admire and, occasionally, sample!

Aside from the sumptuously sweet fruit, the scorching heat in Turpan has other benefits. Sand Therapy is a practice that dates back over hundreds of years and involves burying people in 50 °C (122 °F) to 60 °C (140 °F) sand in order to treat various ailments, including rheumatism and skin disease. There is even a Sand Therapy Centre in the northwest of the city, which is immensely popular with locals and tourists alike.

Yet perhaps Turpan’s greatest claim to fame is its prestigious heritage and the historical relics that surround it. The Jiaohe Ruins are located in Yarnaz Valley, just 10 kilometres (6 mi) west of the city, and date back over 2,300 years. They are considered one of the most well-preserved ruins of an earthen city in the world and were made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014.

Yet perhaps Turpan’s greatest claim to fame is its prestigious heritage and the historical relics that surround it. The Jiaohe Ruins are located in Yarnaz Valley, just 10 kilometres (6 mi) west of the city, and date back over 2,300 years. They are considered one of the most well-preserved ruins of an earthen city in the world and were made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014.

This heritage site also includes the ruins of Gaochang, another ancient city located at the foot of the Flaming Mountains about 46 kilometres (29 mi) southeast of Turpan. It was once another major city along the Silk Road and was initially built during the 1st century BC. Mummies of both Caucasian and Mongolian ancestry have been found in the Astana Tombs just 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) north of Gaochang and may indicate that it was one of the first multi-ethnic cities in the world.

Not far from these ancient ruins, the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves are a set of cave grottos dating back to between the 5th and 14th centuries. As Buddhism was one of the first religions to be introduced to the area via the Silk Road, Xinjiang witnessed the earliest development of this style of cave art in China. Of the 83 original caves in this complex, only 57 remain and most of these date back to between the 10th and 13th centuries.

About 10 kilometres (6 mi) to the east of Turpan, the Flaming Mountains rise up in the sandy desert. Their unusual name is derived from the burnished red colour of their bedrock, which gives the mountains the appearance of being aflame when hit with direct sunlight. With summer temperatures regularly reaching in excess of 50 °C (122 °F), these mountains are widely considered the hottest spot in China and certainly live up to their fiery name!

Join a travel with us to explore more about Turpan: Explore the Silk Road in China

The customs and taboos of the Uyghur ethnic minority have been informed primarily by their rich history and their pious belief in Islam. When receiving guests, the host will typically offer them the best seats, treat them to some tea or milk, and then provide them with some small snacks, such as dried fruit or sweetmeats. If you are offered a drink, be sure to take the cup with both hands as this is a sign of courtesy. The same applies if you are being offered a gift.

The customs and taboos of the Uyghur ethnic minority have been informed primarily by their rich history and their pious belief in Islam. When receiving guests, the host will typically offer them the best seats, treat them to some tea or milk, and then provide them with some small snacks, such as dried fruit or sweetmeats. If you are offered a drink, be sure to take the cup with both hands as this is a sign of courtesy. The same applies if you are being offered a gift. Throughout their long and illustrious history, the Uyghur people have adopted numerous religions, including shamanism

Throughout their long and illustrious history, the Uyghur people have adopted numerous religions, including shamanism