Extending from the eastern edge of the Tarim Basin right through to the city of Korla, the Lop Desert is an almost perfectly flat expanse of barren sands. There are three major depressions dotted throughout the desert that were once mighty lakes: the Lop Nur Basin, the Kara-Koshun Basin, and the Taitema Lake Basin. In ancient times, these formed the terminal lakes of the Tarim-Konque-Qarqan river system. This lake system was a constant source of confusion and frustration to explorers, as changes in the course of the Tarim River would cause the lakes to change position. In fact, Lop Nur was nicknamed the “Wandering Lake” because, like a wayward bachelor, it struggled to find a place and settle down!

Tragically, due to human intervention, the lakes of the Lop Desert have long dried up, but they once played a focal historical role in the development of the region. The capital of the ancient Loulan Kingdom was established near to Lop Nur sometime during the 2nd century BC and swiftly became an oasis city of paramount importance. When the kingdom fell under Chinese control during the 1st century BC, it was renamed Shanshan, but was unfortunately abandoned at some point during the 7th century AD. The site would remain hidden for over a thousand years, until it was rediscovered by the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin in 1899.

His excavation efforts revealed a number of houses and yielded several Chinese manuscripts from the Jin Dynasty (265-420), but the most magnificent discovery was yet to come. During the 20th century, Chinese archaeologists began excavating the area and came across a series of cemeteries. When the ancient graves were opened, they found mummies and burial items that had been beautifully preserved thanks to the extreme dryness of the desert climate. Among them was the “Beauty of Loulan”, who was so-named because of her long hair, soft skin, and peaceful expression. What makes the Beauty of Loulan and her neighbouring mummies so special is that their features are almost fully intact, in spite of the fact that they died over 3,000 years ago! Many of these mummies were of Indo-European origin and are believed to be a lost people known as the Tocharians.

When properly excavated, the earlier settlements near Lop Nur contained more primitive items, such as Mesolithic stone tools, basketry, bows, arrows, the horns of animals, simple jewellery, and fragments of copper. The later settlements were characterised by more advanced signs of civilization, including a canal, a dome-shaped Buddhist stupa[1], and the home of a Chinese official. According to historical records, Lop Nur boasted a length and breadth of roughly 120 to 160 kilometres (76 to 99 mi) during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), but had already shrunk considerably by start of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). The building of dams by Chinese garrisons during the 20th century sounded the death knell for the lake, as it slowly withered into a salty marsh. Nowadays it is nothing more than a dried-up basin covered in a thick crust of salt.

The desiccation of its native lakes, coupled with daytime temperatures that can reach 50 °C (122 °F), means that the Lop Desert is particularly hostile to life. The plethora of freshwater mollusc shells, the extensive belts of dead poplar trees, and the myriad beds of wilted reeds that rest within the wind-etched furrows of towering yardangs[2] are all that remain of what was once a series of verdant oases. When Sven Hedin travelled to the desert during the late 19th century, he witnessed solitary tigers prowling, packs of roving wolves, and groups of wild boar. Nowadays, the only large mammal that can survive in this barren wasteland is the hardy Bactrian camel, which ekes out a meagre living by feeding on the poplar forests and tamarisk shrubs that line the northern edge of the desert. From devastating sandstorms and lofty yardangs to barren salt flats and the blazing heat of the sun, the Lop Desert is an alien landscape that must be navigated with the utmost care.

Notes:

[1] Stupa: A hemispherical structure with a small interior designed for storing Buddhist relics and for private meditation.

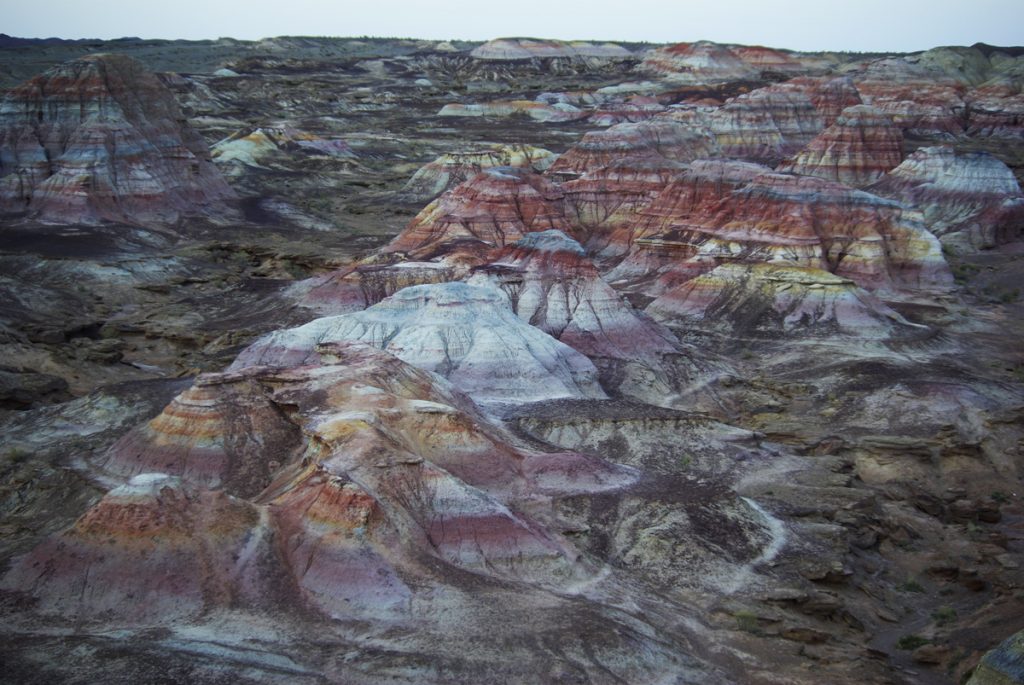

[2] Yardang: A yardang is a type of landform that results from severe weathering over a period of approximately 700,000 years, where wind and rain strip all of the soft material from the rocks and leave only the hard material behind. Yardangs have characteristically wide bottoms that gradually taper off towards the top, giving them an appearance similar to the hull of a boat, although there are huge variations in their size and shape.

The city of Turpan, also known as Turfan, lies about 180 kilometres (112 mi) southeast of the regional capital of Ürümqi, on the northern edge of the deep Turpan Depression. The Bogda Mountains, an eastern extension of the Tian Shan Mountains, rest to the north, while Qoltag Mountain rises to the south. Its unusual location means its climate is pretty unique, with long hot summers and cold brief winters.

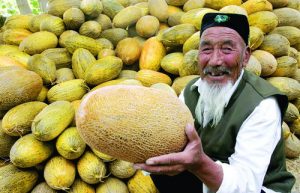

The city of Turpan, also known as Turfan, lies about 180 kilometres (112 mi) southeast of the regional capital of Ürümqi, on the northern edge of the deep Turpan Depression. The Bogda Mountains, an eastern extension of the Tian Shan Mountains, rest to the north, while Qoltag Mountain rises to the south. Its unusual location means its climate is pretty unique, with long hot summers and cold brief winters. Nowadays the abundant sunshine and high temperatures in the city mean that it’s the ideal place for growing several types of fruit, particularly grapes and melons. The

Nowadays the abundant sunshine and high temperatures in the city mean that it’s the ideal place for growing several types of fruit, particularly grapes and melons. The  Yet perhaps Turpan’s greatest claim to fame is its prestigious heritage and the historical relics that surround it. The

Yet perhaps Turpan’s greatest claim to fame is its prestigious heritage and the historical relics that surround it. The

The customs and taboos of the Uyghur ethnic minority have been informed primarily by their rich history and their pious belief in Islam. When receiving guests, the host will typically offer them the best seats, treat them to some tea or milk, and then provide them with some small snacks, such as dried fruit or sweetmeats. If you are offered a drink, be sure to take the cup with both hands as this is a sign of courtesy. The same applies if you are being offered a gift.

The customs and taboos of the Uyghur ethnic minority have been informed primarily by their rich history and their pious belief in Islam. When receiving guests, the host will typically offer them the best seats, treat them to some tea or milk, and then provide them with some small snacks, such as dried fruit or sweetmeats. If you are offered a drink, be sure to take the cup with both hands as this is a sign of courtesy. The same applies if you are being offered a gift.