The Terracotta Army is commonly regarded as one of the Eight Wonders of the Ancient World and has received great international fame and praise throughout the years. In 1987 it was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site and has remained one of the most culturally significant sites in China since the day it was first discovered. The Terracotta Army is located 37 kilometres to the east of Xi’an city in the Museum of Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses. The Army was established as part of the mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China and the first person to unify the regions that make up modern day China. The history of the Terracotta Army is delicately intertwined with the history of China itself. A trip to the Terracotta Army rewards the visitor with a surreal, almost chilling, insight into what coming face to face with Qin Shi Huang’s formidable army would have been like.

Historian Sima Qian[1] recorded that the building of Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum began in 246 B.C., when the Emperor was only 13 years old, and supposedly took over 700,000 labourers and 11 years to complete. Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum was built on Mount Li because, with its rich gold and jade mines, it was considered a particularly auspicious location. The mausoleum was designed to protect the Emperor and provide him with everything he would need in the afterlife. Thus the mausoleum is a necropolis, an immemorial, stone representation of the palace that Qin Shi Huang occupied in life, with offices, halls, stables, towers, ornaments, officials, acrobats and, most importantly, a lifelike replica of his army. The presence of the necropolis was corroborated by Sima Qian, who mentions all of the features of the Mausoleum except, rather bizarrely, the Terracotta Army.

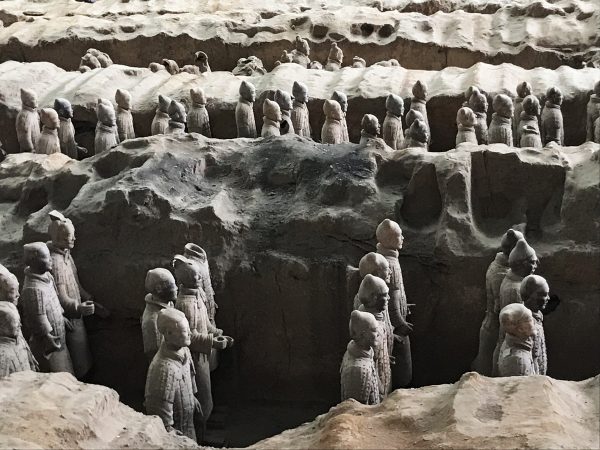

After the death of the Emperor in 210 B.C., the Mausoleum was hermetically-sealed and remained unopened for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until 1974, when some farmers were attempting to dig a water-well near Mount Li, that Pit one of the Terracotta Army was accidentally unearthed. Archaeologists flocked to the site and began excavating the area, eventually discovering three more pits of Terracotta Warriors in the process. The warriors were all found arranged as if to protect the tomb from the east, which is where all of the states that were conquered by the Qin Dynasty lay. To date, approximately 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses and 150 cavalry horses have been uncovered from these pits.

After the death of the Emperor in 210 B.C., the Mausoleum was hermetically-sealed and remained unopened for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until 1974, when some farmers were attempting to dig a water-well near Mount Li, that Pit one of the Terracotta Army was accidentally unearthed. Archaeologists flocked to the site and began excavating the area, eventually discovering three more pits of Terracotta Warriors in the process. The warriors were all found arranged as if to protect the tomb from the east, which is where all of the states that were conquered by the Qin Dynasty lay. To date, approximately 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses and 150 cavalry horses have been uncovered from these pits.

Pit one of the Terracotta Army is still by far the most impressive, boasting 6,000 figures arranged in their original military formation. Pit two contains the cavalry and infantry units, as well as a few war chariots. It is thought to represent a military guard. Pit three is thought to be the command post since it contains high-ranking officers and a war chariot. Pit four has been left empty for unknown reasons, although it has been posited that perhaps it was simply left unfinished by its builders. Other non-military terracotta figures have been found in other pits, such as officials, acrobats and musicians, but these pits are not arranged in the same way as those containing the Terracotta Army.

What makes the Terracotta Army so brilliantly unique, on top of its impressive size, is the fact that every single figure is different. Their height, uniform and hairstyle are all different, depending on military rank, and the face of each warrior has been uniquely moulded based on a living counterpart. Originally the figures were all beautifully painted and held real weapons but tragically most of the paint flaked off when it was exposed to dry air during the excavation and the weapons had almost all been looted long before the site was excavated. In Pits one and two there is evidence of fire damage and it has been posited that Xiang Yu, a contender to the throne after the death of the first Emperor, may have looted the tombs, taken the weapons and attempted to destroy the army. Many of the current warriors on display have been pieced together from fragments as they were badly damaged when the roof rafters collapsed during the fire.

In spite of this unfortunate damage, some of the figures have maintained their colour, such as the famed Green-Faced Soldier[2] of Pit two, and some weapons, such as swords, spears, battle-axes, scimitars, shields, crossbows, and arrowheads, have been recovered from the pits. Some of the weapons were coated with a layer of chromium dioxide, which has kept them rust-free for nearly 2,000 years. Some are still sharp and carry inscriptions that date manufacture between 245 and 228 B.C., meaning they were used in combat before they were buried here.

It is important to note that each warrior was not moulded and fired as it is now but was crafted as part of the first known assembly line to have existed in the civilised world. The heads, arms, legs, and torsos of each warrior were created separately at separate workshops and then assembled later on. It is believed that originally only eight face moulds were used and then clay was added and sculpted onto the face after assembly to give each warrior their individual facial features. During the time these figures were being mass produced, each workshop was required to inscribe its name on whatever part it had made, which is how we know that each part of the warriors and other figures was manufactured separately.

When the British Museum held an exhibition of the Terracotta Warriors from 2007 to 2008, exhibiting a small selection of real figures from the excavation sites, it resulted in the most successful year they had since the King Tutankhamen exhibition in 1972. So popular and stunning are the Terracotta Warriors that they have attracted attention worldwide, bringing about some of the most successful exhibitions in the world, including one at the Forum de Barcelona in Barcelona and one at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. If the possibility of seeing them individually has managed to generate this much hype, imagine what it must be like to see them altogether, in military formation, in almost the exact same positions they were in when they were originally placed in their tombs.

The Museum of Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses and the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum have now been incorporated into one tourist attraction known as Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Site Park. There you’ll find regular free shuttle buses that will take you from the site of the Terracotta Army to Lishan Garden. Lishan Garden acts as the perfect complement to the Terracotta Army as it contains Qin Shi Huang’s burial mound, ritual sacrifice pits, the Museum of Terracotta Acrobatics, the Museum of Terracotta Civil Officials, the Museum of Stone Armour and the Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses. The Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses is a wonderful exhibition of all the figures found throughout the pits that are crafted from bronze rather than terracotta. They loom out of their glass cases, lifelike in their shimmering skin. The other museums are based around pits where terracotta figures are still being excavated and present the perfect opportunity to watch a live archaeological dig. The chance to watch the Terracotta figures being unearthed and thus the opportunity to watch history being made is one that we know you won’t want to pass up. The only area that is not open to the public and has not been excavated is the main tomb, where the Emperor’s remains rest. In spite of an on-going debate as to whether the tomb should be opened or not, it is universally thought that it will remain undisturbed as a mark of respect to the Emperor.

The Museum of Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses and the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum have now been incorporated into one tourist attraction known as Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Site Park. There you’ll find regular free shuttle buses that will take you from the site of the Terracotta Army to Lishan Garden. Lishan Garden acts as the perfect complement to the Terracotta Army as it contains Qin Shi Huang’s burial mound, ritual sacrifice pits, the Museum of Terracotta Acrobatics, the Museum of Terracotta Civil Officials, the Museum of Stone Armour and the Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses. The Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses is a wonderful exhibition of all the figures found throughout the pits that are crafted from bronze rather than terracotta. They loom out of their glass cases, lifelike in their shimmering skin. The other museums are based around pits where terracotta figures are still being excavated and present the perfect opportunity to watch a live archaeological dig. The chance to watch the Terracotta figures being unearthed and thus the opportunity to watch history being made is one that we know you won’t want to pass up. The only area that is not open to the public and has not been excavated is the main tomb, where the Emperor’s remains rest. In spite of an on-going debate as to whether the tomb should be opened or not, it is universally thought that it will remain undisturbed as a mark of respect to the Emperor.

Emperor Qin Shi Huang wanted to build a monument to his achievements that would last throughout the ages. With his stunning Terracotta Army, whose popularity has not waned since they were unearthed, still standing in their original military formation as a testament to his prowess, I think you’ll agree that he achieved what he set out to do. Thanks to this incredible feat, China’s first Emperor has made himself truly immortal.

[1] Sima Qian (145–90 BCE): A Chinese historian whose most noted work was called “Shiji” or “Records of the Grand Historian”

[2] The Green-Faced Soldier: A single Terracotta Warrior whose face has inexplicably been painted green instead of pink

The Terracotta Army is one of the many wonderful stops on travel Explore the Silk Road in China and Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages

Northern Shaanxi is north of the Beishan Mountains and consists primarily of the Loess Plateau and the Maowusu Desert. It has cold and very dry winters, dry springs and autumns, and hot summers. Central Shaanxi, also known as Guanzhong, is the home of Xi’an and Mount Huashan. It is located south of the Beishan Mountains and north of the Qinling Mountains. This area enjoys cool to cold winters, and hot, humid summers. Southern Shaanxi is to the south of the Qinling Mountains and is well known for its stunning natural attractions, such as Nangong Mountain National Forest Park and Yinghu Lake. This area enjoys temperate winters and long, hot, humid summers. The annual mean temperature of the province is roughly between 8 to 16 °C (46 to 61 °F), plummeting to lows of up to -11 °C (12.2 °F) in the winter and reaching highs of up to 28 °C (82 °F) in the summer.

Northern Shaanxi is north of the Beishan Mountains and consists primarily of the Loess Plateau and the Maowusu Desert. It has cold and very dry winters, dry springs and autumns, and hot summers. Central Shaanxi, also known as Guanzhong, is the home of Xi’an and Mount Huashan. It is located south of the Beishan Mountains and north of the Qinling Mountains. This area enjoys cool to cold winters, and hot, humid summers. Southern Shaanxi is to the south of the Qinling Mountains and is well known for its stunning natural attractions, such as Nangong Mountain National Forest Park and Yinghu Lake. This area enjoys temperate winters and long, hot, humid summers. The annual mean temperature of the province is roughly between 8 to 16 °C (46 to 61 °F), plummeting to lows of up to -11 °C (12.2 °F) in the winter and reaching highs of up to 28 °C (82 °F) in the summer.

The history of Fujian is full of such immigrations and emigrations. Fujian people are regarded as some of the bravest people in China, as they are never afraid to venture outside of their homeland and fight for a new life wherever they end up. At the end of the 19th century, the hinterlands of Fujian experienced a sudden wave of emigrations. To avoid the impending poverty, more than a million people from Fujian immigrated to Southeast Asia, where their chances for survival were better. Nowadays there are many people in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore that can trace their lineage back to these Fujian immigrants. The custom of emigration seems to still be a common trend in Fujian. Nowadays, the people of Fujian still frequently try to migrate to other countries. Instead of immigrating to Southeast Asia, the vast majority of them now choose to go to Japan, America and Europe.

The history of Fujian is full of such immigrations and emigrations. Fujian people are regarded as some of the bravest people in China, as they are never afraid to venture outside of their homeland and fight for a new life wherever they end up. At the end of the 19th century, the hinterlands of Fujian experienced a sudden wave of emigrations. To avoid the impending poverty, more than a million people from Fujian immigrated to Southeast Asia, where their chances for survival were better. Nowadays there are many people in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore that can trace their lineage back to these Fujian immigrants. The custom of emigration seems to still be a common trend in Fujian. Nowadays, the people of Fujian still frequently try to migrate to other countries. Instead of immigrating to Southeast Asia, the vast majority of them now choose to go to Japan, America and Europe.

Sorghum Fish (高粱面鱼鱼)

Sorghum Fish (高粱面鱼鱼) He asked the old boatman for some food, and the boatman replied: “All I have is some flour, but I don’t have a rolling pin to make noodles for you”. The boatman’s daughter looked down at the little kitten in her arms and swiftly thought of an idea. She began making the noodles by hand and used her fingers to create small indents in each noodle. Once they were finished, the old boatman cooked them and served them to the Emperor with a simple sauce. The Emperor was overwhelmed by how tasty the noodles were and, when he asked the boatman’s daughter what she wished to call the dish, she decided on “Cat’s Ear Noodles”. When the Emperor returned to his palace, he hired her to be his chef and, from that day onwards, her family wanted for nothing. What a purr-fect ending!

He asked the old boatman for some food, and the boatman replied: “All I have is some flour, but I don’t have a rolling pin to make noodles for you”. The boatman’s daughter looked down at the little kitten in her arms and swiftly thought of an idea. She began making the noodles by hand and used her fingers to create small indents in each noodle. Once they were finished, the old boatman cooked them and served them to the Emperor with a simple sauce. The Emperor was overwhelmed by how tasty the noodles were and, when he asked the boatman’s daughter what she wished to call the dish, she decided on “Cat’s Ear Noodles”. When the Emperor returned to his palace, he hired her to be his chef and, from that day onwards, her family wanted for nothing. What a purr-fect ending!

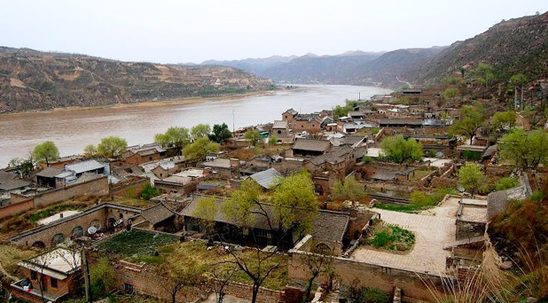

Although it may no longer be the glorious trade port it once was, Qikou is still a picturesque ancient town with many historic buildings that have been beautifully preserved. In order to protect them from flooding, many of these houses, known as “yaodongs” or “loess cave houses,” have been physically carved into the steep hillside along the banks of the Yellow River. Looming over these houses on a raised platform, the Black Dragon Temple is the ideal place to enjoy a panoramic view of town. The temple is dedicated primarily to two separate deities: the legendary Black Dragon; and Guan Yu, a military general from the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280) who was eventually deified.

Although it may no longer be the glorious trade port it once was, Qikou is still a picturesque ancient town with many historic buildings that have been beautifully preserved. In order to protect them from flooding, many of these houses, known as “yaodongs” or “loess cave houses,” have been physically carved into the steep hillside along the banks of the Yellow River. Looming over these houses on a raised platform, the Black Dragon Temple is the ideal place to enjoy a panoramic view of town. The temple is dedicated primarily to two separate deities: the legendary Black Dragon; and Guan Yu, a military general from the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280) who was eventually deified.

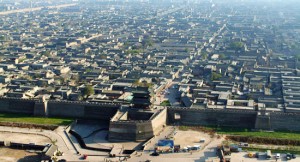

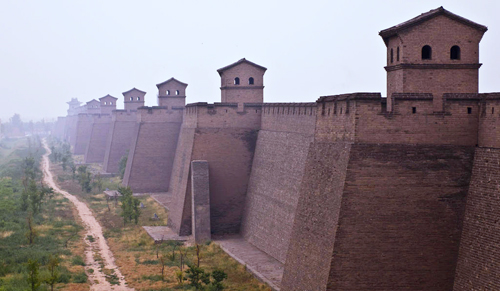

The walls are punctuated by six barbican gates in total, with one each on the north and south sides, and two each on the west and east sides. From an aerial perspective, this supposedly makes Pingyao look like a tortoise, with the west and east gates as the legs, the north gate as the tail, the south gate as the head, and the criss-crossing lanes within as the patterns on its shell. This has earned it the nickname the “Tortoise City”!

The walls are punctuated by six barbican gates in total, with one each on the north and south sides, and two each on the west and east sides. From an aerial perspective, this supposedly makes Pingyao look like a tortoise, with the west and east gates as the legs, the north gate as the tail, the south gate as the head, and the criss-crossing lanes within as the patterns on its shell. This has earned it the nickname the “Tortoise City”!

Alongside the city walls and Rishengchang, the other major attractions within the ancient city are the County Government Office and the Temple of the City God. While the County Government Office was designed to rule the “yang” of the human world, the Temple of the City God held sway over the “yin” of the spiritual world. These two buildings were placed on the same street in order to balance each other out, with the office in the west and the temple in the east. The County Government Office was originally built in 1346, during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), and is the largest of its kind in China. It represented a vast complex containing the home of the local magistrate, various offices, a prison, a court, meeting rooms, and a scenic garden.

Alongside the city walls and Rishengchang, the other major attractions within the ancient city are the County Government Office and the Temple of the City God. While the County Government Office was designed to rule the “yang” of the human world, the Temple of the City God held sway over the “yin” of the spiritual world. These two buildings were placed on the same street in order to balance each other out, with the office in the west and the temple in the east. The County Government Office was originally built in 1346, during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), and is the largest of its kind in China. It represented a vast complex containing the home of the local magistrate, various offices, a prison, a court, meeting rooms, and a scenic garden.