The Great Wall spans over large parts of northern China, and is the result of thousands of years of construction. In 1988 it was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and in 2007 it was named as one of the New Seven Wonders of the World. Officially it extends for approximately 8,850 kilometres (5,500 miles) from east to west, making it 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) longer than the River Nile!

The history behind this practically legendary feat of architecture began during the Warring States Period (c. 476-221 BC). At that time, China was separated into seven large empires known as the states of Qin, Han, Wei, Zhao, Qi, Chu, and Yan, along with a few smaller kingdoms. In an effort to protect themselves from both inside and outside threats, many of these states began to build walls around their respective territories. The State of Chu pioneered this defensive trend in the 7th century BC when they constructed the “Square Wall”. From the 6th to the 4th century, the other six states followed suit and soon the country was littered with fortifications made of stone, packed earth, and anything they could get their hands on!

When the first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, unified China in 221 BC, he was left with the unenviable task of dealing with this labyrinth of walls. He began by ordering the destruction of all fortifications that had been set up between the conquered six states, as they only presented obstacles to internal administration. However, he soon realised that he could use several of the walls to protect his newly unified China from the nomadic Xiongnu people.

In 214 BC, he ordered the construction of connections between the existing walls that had belonged to the States of Qin, Yan, and Zhao. Ten years later, the “10,000-li[1] Long Wall” was completed. Hundreds of thousands of conscripted workers were forced to labour on the wall and many of them perished. When Qin Shi Huang died in 210 BC, the wall largely fell into disrepair.

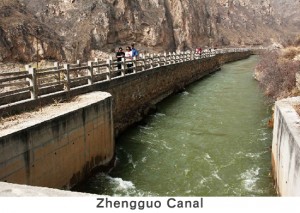

That is until the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), when Emperor Wudi’s campaign against the Xiongnu revived interest in the wall as a northern defence system. He began strengthening it not only to protect the country from invasion, but also to help the imperial court control trade routes between China and Central Asia. When the Northern Wei (386-534) and Northern Qi (550-577) dynasties took control of northern China, they too invested in extensive repairs to help defend against potential invasions.

That is until the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), when Emperor Wudi’s campaign against the Xiongnu revived interest in the wall as a northern defence system. He began strengthening it not only to protect the country from invasion, but also to help the imperial court control trade routes between China and Central Asia. When the Northern Wei (386-534) and Northern Qi (550-577) dynasties took control of northern China, they too invested in extensive repairs to help defend against potential invasions.

During the Sui Dynasty (581-618), in light of the looming threat represented by the Tujue people, the wall was repaired and extended. However, when the Tang Dynasty (618-907) took over, their military prowess allowed them to defeat the Tujue and expand China’s territory further north. Thus the wall gradually became defunct and was neglected for several years.

This was all to change during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when the Liao and Jin tribes in the north presented a constant threat. The Song rulers were forced to withdraw behind the wall and relinquish their northern territory. Extensive repairs and additions to the wall continued until the Song court was forced to retreat even further south towards the Yangtze River. Since the Mongol leaders of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) already controlled a vast empire outside of China, they had little use for the wall and only garrisoned a handful of key areas predominantly to monitor trade and travel.

It was during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) that the wall would finally achieve the accolade and greatness it sorely deserved. The Ming leaders tirelessly maintained, strengthened, and extended it in the hopes of staving off another Mongolian invasion. When people talk about “The Great Wall” of China, they are usually referred to the Ming Great Wall, which stretches from Tiger Mountain in the east to the Jiayu Pass in the west, as the sections of this wall around Beijing and Hebei province are in decent condition. While these sections were largely constructed with bricks, many of the ones in Shanxi Province were built using solid clay. Further west there are still some relics of the Han Great Wall, such as Yumen Pass and Yang pass, but these are largely incomplete when compared with the Ming Great Wall. The most heavily garrisoned areas along this wall were the Three Inner Passes (Juyong, Daoma, and Zijing) and the Three Outer Passes (Yanmen, Ningwu, and Piantou), which were key to the protection of Beijing.

It was during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) that the wall would finally achieve the accolade and greatness it sorely deserved. The Ming leaders tirelessly maintained, strengthened, and extended it in the hopes of staving off another Mongolian invasion. When people talk about “The Great Wall” of China, they are usually referred to the Ming Great Wall, which stretches from Tiger Mountain in the east to the Jiayu Pass in the west, as the sections of this wall around Beijing and Hebei province are in decent condition. While these sections were largely constructed with bricks, many of the ones in Shanxi Province were built using solid clay. Further west there are still some relics of the Han Great Wall, such as Yumen Pass and Yang pass, but these are largely incomplete when compared with the Ming Great Wall. The most heavily garrisoned areas along this wall were the Three Inner Passes (Juyong, Daoma, and Zijing) and the Three Outer Passes (Yanmen, Ningwu, and Piantou), which were key to the protection of Beijing.

When the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) replaced the Ming, they changed their ruling strategy to one known as huairou or “mollification”. This was where the Qing court would pacify peoples from Mongolia, Tibet, and other nationalities within their territory by allowing them to continue with their social, cultural, and religious lifestyles uninterrupted. This strategy was so successful that the Great Wall was largely unneeded and fell into disrepair once again. That is, until Chinese businessmen discovered what a valuable tourist attraction it was!

Construction

To maximize the effectiveness of the Great Wall, several mountains were incorporated into it as natural barriers and these account for about a quarter of its length. This helped prevent the construction costs from becoming too steep! That being said, over 70% of it is made up of manmade wall, which is incredibly impressive. It consists of three main components: passes, signal towers, and walls.

The passes represented the greatest strongholds and were usually located at strategically significant points, such as along trade routes. They served as access points for merchants and civilians, as well as exits for soldiers when they performed counterattacks or went out on patrols. On average, the bastions measured 10 metres (30 ft.) in height and were 4 to 5 metres (13-16 ft.) wide at the top. The outside was crenelated while the inside was marked by a metre-high (3 ft.) wall that prevented people or horses from falling off the top. Let’s just hope no one was clumsy enough to trip over the wall!

Signal towers were used to communicate along the wall via the use of beacons (lanterns) at night or smoke signals during the day. In addition, soldiers stationed at the towers would raise banners, beat clappers, or fire guns to convey certain messages. For example, one release of smoke with one shot of gunfire signified the approach of 100 enemies, while three smoke releases with three gunshots indicated more than 1,000. Once one tower spotted the signal, they would replicate it in order to warn towers further down the line. Kind of like forwarding work emails!

Signal towers were used to communicate along the wall via the use of beacons (lanterns) at night or smoke signals during the day. In addition, soldiers stationed at the towers would raise banners, beat clappers, or fire guns to convey certain messages. For example, one release of smoke with one shot of gunfire signified the approach of 100 enemies, while three smoke releases with three gunshots indicated more than 1,000. Once one tower spotted the signal, they would replicate it in order to warn towers further down the line. Kind of like forwarding work emails!

The walls themselves are on average 7 to 8 metres (23-26 ft.) in height and 6 metres (19 ft.) in width. To put that into perspective, they’re so wide that five horses could gallop side by side with room to spare! Their structure varies from place to place and largely depended on the kinds of building materials that were available. For example, in the western deserts the walls are mainly made of rammed earth, while in the eastern regions they are faced with stones from outlying mountains.

The Legend of Meng Jiangnu

Of all the myths associated with the Great Wall, the legend of Meng Jiangnu is the most famous and ranks as one of China’s Four Great Folktales. The legend takes place during the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), around the time that Emperor Qin Shi Huang announced his intentions to build the Great Wall. A beautiful girl named Meng Jiangnu was tending her family’s garden when she caught sight of a young scholar named Fan Qiliang, who was hiding from the federal officials as he did not want to labour on the wall. As with all good fairy tales, they fell in love at first sight and agreed to marry. But, just three days after the wedding, officials broke into their home and took Fan away.

For many months, Meng heard nothing about her husband and so resolved to travel to the wall herself. Upon her arrival, her eagerness to see him was matched only by her despair when she discovered that he had died of exhaustion. She sat on the ground and wept so bitterly that her cries caused a 400-kilometre-long (248 mi) stretch of the wall to collapse and reveal the bones of her deceased lover.

Meanwhile, the Emperor happened to be touring the wall and was enraged to find part of it had been destroyed. Yet, the moment he set eyes upon Meng, he was transfixed by her beauty and, instead of executing her, he asked her to marry him. She agreed, but only on three conditions: a festival should be held in her husband’s honour; a state funeral should be conducted for him; and a terrace should be built on the wall near the river so she could make sacrificial offerings to him.

Meanwhile, the Emperor happened to be touring the wall and was enraged to find part of it had been destroyed. Yet, the moment he set eyes upon Meng, he was transfixed by her beauty and, instead of executing her, he asked her to marry him. She agreed, but only on three conditions: a festival should be held in her husband’s honour; a state funeral should be conducted for him; and a terrace should be built on the wall near the river so she could make sacrificial offerings to him.

The Emperor reluctantly met her terms but, before their wedding, she climbed the newly built terrace, cursed him and threw herself into the river. This tragic tale embodies the cruelty of the first emperor and honours the many workers who lost their lives building the wall. The Temple of Meng Jiangnu can be found near Shanhai Pass and dates all the way back to the Song Dynasty.

Badaling

The Badaling section of the Great Wall is arguably the most famous and attracts thousands of visitors every day. It rests near the city of Zhangjiakou, just 70 kilometres (43 mi) northwest of Beijing, and was the first section to be opened to the public. Although it was originally built in 1505, it was rebuilt during the 1950s and is thus one of the most “complete” sections of the Great Wall. It stretches over 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) and contains 43 signal towers.

Jiankou

Jiankou

The term “jiankou” means “nocked arrow” and this section of the Great Wall was so-named because part of it resembles a large sideways “W”, like an arrow that is ready to shoot. It is located just outside Xizhazi Village, about 30 kilometres (19 mi) from Huairou County.

A few highlights along this part of the wall include: the Nine-Eye Tower, a command tower that has nine holes resembling nine eyes on each side; the Sky Stairs, a set of stairs that elevate at a dizzying angle of 70 to 80 degrees; and “The Eagle Flies Facing Upward”, a watch tower built so high up that supposedly even eagles would have to fly facing upward to reach the top!

Mutianyu

Mutianyu

Mutianyu was originally built during the Northern Qi Dynasty (550-557) and stretches approximately 2 kilometres (1.5 mi) from the Juyong Pass in the west to the Gubeikou section in the east. Since it protected one of the passes leading to Beijing, it was repaired regularly throughout the Ming Dynasty and is now considered one of the most well-preserved parts of the Great Wall. It was partly made of granite and is considered virtually indestructible!

Jinshanling

At its western point, Jinshanling is connected with Simatai and, together with Simatai, it is also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

At its western point, Jinshanling is connected with Simatai and, together with Simatai, it is also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Jinshanling portion of the Great Wall consists of 67 towers and is approximately 11 kilometres (7 mi) long. It has been repaired several times and appears to be as well-developed as Badaling. However, thus far there are substantially fewer tourists here than at Badaling. If you want to witness the Great Wall in its complete glory, Jinshanling is the best place to go. The refurbishment that it has undergone has not altered its original appearance too much. All of the components of the original Great Wall – the tower, the gate, the fire beacon tower—are still there.

Panlongshan

The Panlongshan or “Coiling Dragon Mountain” section of the Great Wall is the part of the Gubeikou section of the Great Wall that connects to the Jinshanling section.

The Panlongshan or “Coiling Dragon Mountain” section of the Great Wall is the part of the Gubeikou section of the Great Wall that connects to the Jinshanling section.

The main highlights of the Panlongshan section are the General Tower and 24-Window Tower. The General Tower is a two-storey, square-shaped structure that originally functioned as the office of the military general who managed this section of the wall, while the 24-Window Tower is the final watchtower along the Panlongshan Section. The northwestern side of the 24-Tower Window has completely collapsed, which endows it with a certain ruined beauty that has attracted the admiration of many visitors.

Simatai

Historically, the Simatai segment was considered the most impenetrable stronghold along the Great Wall as it’s built across a particularly unforgiving stretch of mountains. It’s located near Gubeikou Town in Miyun County and is about 5 kilometres (3 mi) long. According to legend, its Fairy Maiden Tower was home to a beautiful sprite named the Lotus Flower Fairy and is thus beautifully decorated with marble engravings of lotus flowers.

Historically, the Simatai segment was considered the most impenetrable stronghold along the Great Wall as it’s built across a particularly unforgiving stretch of mountains. It’s located near Gubeikou Town in Miyun County and is about 5 kilometres (3 mi) long. According to legend, its Fairy Maiden Tower was home to a beautiful sprite named the Lotus Flower Fairy and is thus beautifully decorated with marble engravings of lotus flowers.

Highlights along this section of the Great Wall include: the Wangjing Tower, which rests at a staggering elevation of about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft.); and the Stairway to Heaven, the 100-metre-long (330 ft.) path that connects the aforementioned towers and is only 30 centimetres (12 in) wide, with cliffs on both sides!

The Jiaoshan Section of the Great Wall

Known as the “First Mountain of the Great Wall”, Jiaoshan earned its unusual nickname simply because it is the first mountain that the Great Wall climbs after it begins in the east. In fact, the term “Jiaoshan” literally translates to mean “Horn Peak” due to its profound steepness. This section of the wall was built during the early Ming Dynasty and thus boasts a history that is over 600 years long!

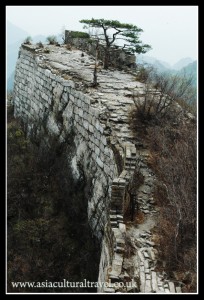

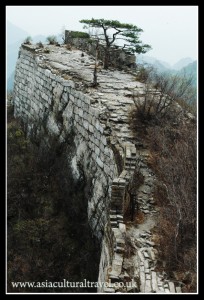

What makes this section of the wall so unusual is that parts of it have been renovated in recent years, but other parts have been left to grow wild. This gives Jiaoshan a hybrid appearance, as both a beautifully preserved and partially crumbling section of the wall.

A major highlight at Jiaoshan is known as Big Flat Summit and represents the highest point of this section. From the top, visitors are rewarded with a breathtaking panoramic view of the surrounding Yan Mountains.

The Dongjiakou Section of the Great Wall

The Dongjiakou section of the Great Wall is widely considered to be one of the best-preserved sections of the original Ming Dynasty wall. It is estimated that around 60% of this section has been preserved in its original condition.

This is allegedly due to the efforts of locals from the nearby village of Dongjiakou, who are said to be the descendants of the original builders and guards of this part of the wall! They take their ancestral heritage very seriously and inspect the wall on a regular basis, making repairs as and when they are needed.

The Dongjiakou section is also renowned for its bricks, some of which have been carved with various images that are typical of the folk art style of southern China. This sets it apart from other sections of the Great Wall, which are invariably constructed from blank bricks.

The Huangyaguan Section of the Great Wall

Huangyaguan or Huangya Pass was once one of the most important fortresses along the Great Wall. It was originally constructed during the Northern Qi Dynasty (550-577 AD), but the wall we see today is a result of major renovations that took place in 1569, during the Ming Dynasty, under the supervision of the renowned general Qi Jiguang.

Huangyaguan or Huangya Pass was once one of the most important fortresses along the Great Wall. It was originally constructed during the Northern Qi Dynasty (550-577 AD), but the wall we see today is a result of major renovations that took place in 1569, during the Ming Dynasty, under the supervision of the renowned general Qi Jiguang.

Its name, which translates to mean “Yellow Cliff Pass”, is derived from the fact that the cliffs to the east of the pass are made of yellow rocks that supposedly appear as though they’ve been gilded in gold when hit by the soft glow of the sunset.

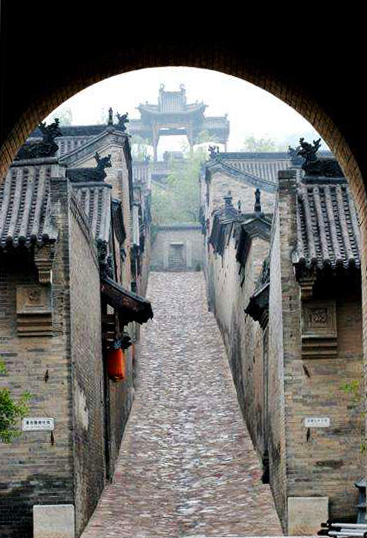

The pass itself is often playfully referred to as the “Eight Diagram Fortification City”, as its labyrinth of narrow streets supposedly resembles the “Bagua” or “Eight Trigrams” symbol that forms an integral part of traditional Chinese culture.

The Chengziyu Section of the Great Wall

Unlike other sections of the Great Wall, which are named for their unusual shape or their lofty historical significant, the Chengziyu section is named simply after the nearby village of Chengziyu. The section itself is divided in the middle by a large valley, which separates the east part from the west part. This valley was once home to the Chengziyu Pass, which has tragically fallen to ruin.

The Baiyangyu Section of the Great Wall

The Baiyangyu section of the Great Wall is located in Qian’an of Hebei province, beginning at Da’ao Tower in the east and ending at the Laojuntai Terrace of the Sidaogou section in the west. It was originally constructed towards the beginning of the Ming Dynasty and was greatly enhanced during the dynasty’s later years. It stretches for a whopping 4,550 metres in length and includes 1,500 metres of marble walling, which is highly unusual when compared to other sections of the Great Wall. This marble section of the Great Wall is 10 metres high and 5 metres wide. Of the 21 towers that once guarded this section of the wall, 6 of them are still in good condition.

The Baiyangyu section of the Great Wall is located in Qian’an of Hebei province, beginning at Da’ao Tower in the east and ending at the Laojuntai Terrace of the Sidaogou section in the west. It was originally constructed towards the beginning of the Ming Dynasty and was greatly enhanced during the dynasty’s later years. It stretches for a whopping 4,550 metres in length and includes 1,500 metres of marble walling, which is highly unusual when compared to other sections of the Great Wall. This marble section of the Great Wall is 10 metres high and 5 metres wide. Of the 21 towers that once guarded this section of the wall, 6 of them are still in good condition.

Unlike the Badaling section of the Great Wall, which is arguably the most famous, the Baiyangyu section receives markedly few visitors and has fallen into a state of disrepair, endowing it with a wild beauty that sets it apart from more complete sections of the wall. Thus it represents the ideal opportunity to enjoy a quiet hike through the countryside while simultaneously appreciating one of the greatest architectural achievements of mankind.

Shanhai Pass

The name “Shanhai Pass” literally means “Mountain and Sea Pass” because it is strategically placed so it joins the Bohai Sea to the southeast and the Yanshan Mountains to the northwest. It was built during the Ming Dynasty and is one of the most well-preserved passes along the Great Wall. Many historians believe it was the eastern starting point of the Great Wall and above its East Gate there is a famous inscription which reads “First Pass Under Heaven”. This refers to the traditional view of Chinese civilization behind the wall and barbarian lands to the north of it, though we’re sure those “barbarians” might have a different view of the situation. In an act of ironic revenge, the pass was eventually captured by one such barbarian tribe named the Jurchen people, who went on to establish the Qing Dynasty!

The name “Shanhai Pass” literally means “Mountain and Sea Pass” because it is strategically placed so it joins the Bohai Sea to the southeast and the Yanshan Mountains to the northwest. It was built during the Ming Dynasty and is one of the most well-preserved passes along the Great Wall. Many historians believe it was the eastern starting point of the Great Wall and above its East Gate there is a famous inscription which reads “First Pass Under Heaven”. This refers to the traditional view of Chinese civilization behind the wall and barbarian lands to the north of it, though we’re sure those “barbarians” might have a different view of the situation. In an act of ironic revenge, the pass was eventually captured by one such barbarian tribe named the Jurchen people, who went on to establish the Qing Dynasty!

Jiayu Pass

Shanhai may be the “First Pass Under Heaven”, but Jiayu Pass is commonly referred to as the “First and Greatest Pass Under Heaven”. Talk about one-upmanship! It earned this title primarily because it was built around about 1372, during the early Ming Dynasty, and is one of the most well-preserved military buildings remaining along the Great Wall. It is located at the narrowest point along the western section of the Hexi Corridor in Gansu province, about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) southwest of Jiayuguan city, and it represents the first pass at the western end of the wall. It was once both a vital fortification for protecting the northwestern border and also a significant point along the ancient Silk Road.

Shanhai may be the “First Pass Under Heaven”, but Jiayu Pass is commonly referred to as the “First and Greatest Pass Under Heaven”. Talk about one-upmanship! It earned this title primarily because it was built around about 1372, during the early Ming Dynasty, and is one of the most well-preserved military buildings remaining along the Great Wall. It is located at the narrowest point along the western section of the Hexi Corridor in Gansu province, about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) southwest of Jiayuguan city, and it represents the first pass at the western end of the wall. It was once both a vital fortification for protecting the northwestern border and also a significant point along the ancient Silk Road.

According to legend, when the pass was being planned, the official charged with its construction approached the designer and asked him to estimate the number of bricks they would need. The designer emphatically replied that they needed exactly 99,999 bricks but the official flew into a rage, believing the designer to be overconfident in his abilities. He demanded that the designer compensate for any potential oversights by ordering more bricks and, as an act of defiance, the designer ordered just one extra brick. In the end, he was right and the one lone brick, left over after the pass’ completion, still rests on top of one of the gates.

[1] Li: A unit of distance used in China that roughly equates to 500 metres (1,640 ft.)

Join a tour to hike along the Great Wall: Explore the Wild Great Wall on Foot

Or Join a tour to have one day hiking on the Great Wall: Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages

Or if you want a customised hiking tour along the wild Great Wall, please send us an Enquiry to info@asiaculturaltravel.co.uk

The Wang Family Compound may not be the most popular of the Shanxi Grand Compounds, but it’s actually four times the size of the renowned Qiao Family Compound and even rivals the Forbidden City in its magnitude! Like many of the Shanxi Grand Compounds, it is located in Lingshi County, approximately 35 kilometres (22 mi) from the ancient city of Pingyao. Stretching over an area of 150,000 square metres (1614587 sq. ft.), its vast complex consists of six castle-like courtyards, six lanes, and one street. In-keeping with its legendary size, its five main courtyards were designed to symbolically represent the five lucky animals according to traditional Chinese culture: the Dragon, the Phoenix, the Tortoise, the Qilin (Chinese Unicorn), and the Tiger. In short, you could say the Wang family were living in the belly of the beast!

The Wang Family Compound may not be the most popular of the Shanxi Grand Compounds, but it’s actually four times the size of the renowned Qiao Family Compound and even rivals the Forbidden City in its magnitude! Like many of the Shanxi Grand Compounds, it is located in Lingshi County, approximately 35 kilometres (22 mi) from the ancient city of Pingyao. Stretching over an area of 150,000 square metres (1614587 sq. ft.), its vast complex consists of six castle-like courtyards, six lanes, and one street. In-keeping with its legendary size, its five main courtyards were designed to symbolically represent the five lucky animals according to traditional Chinese culture: the Dragon, the Phoenix, the Tortoise, the Qilin (Chinese Unicorn), and the Tiger. In short, you could say the Wang family were living in the belly of the beast!

Yet it wasn’t just Qiao Zhiyong’s business acumen that enabled the compound to flourish. During the Qing Dynasty, a military coalition known as the Eight-Nation Alliance was set up in response to the violent Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) in China. Included in this alliance were the Empire of Japan, the Russian Empire, the British Empire, the French Third Republic, the United States, the German Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1900, the alliance sent troops to liberate their embassy in Beijing, which had been under siege. Once they had resolved the issue with the embassy, they decided to invade and occupy the city of Beijing. Talk about taking liberties!

Yet it wasn’t just Qiao Zhiyong’s business acumen that enabled the compound to flourish. During the Qing Dynasty, a military coalition known as the Eight-Nation Alliance was set up in response to the violent Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) in China. Included in this alliance were the Empire of Japan, the Russian Empire, the British Empire, the French Third Republic, the United States, the German Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1900, the alliance sent troops to liberate their embassy in Beijing, which had been under siege. Once they had resolved the issue with the embassy, they decided to invade and occupy the city of Beijing. Talk about taking liberties! After numerous renovations in its 160-year-long history, it now stretches over a staggering 8,724 square metres (93,904 sq. ft.) and is comprised of 6 large courtyards, 20 smaller courtyards, one ancestral temple, and 313 rooms. Its layout is designed to resemble the Chinese character “囍”, which means “happiness” and is meant to symbolically express the Qiao family’s hope for a bright future. Some of its courtyards are flanked at their entrance by fearsome stone guardian lions, while others have their eaves delicately painted with tableaus of Chinese folk legends or their gates engraved with beautiful patterns.

After numerous renovations in its 160-year-long history, it now stretches over a staggering 8,724 square metres (93,904 sq. ft.) and is comprised of 6 large courtyards, 20 smaller courtyards, one ancestral temple, and 313 rooms. Its layout is designed to resemble the Chinese character “囍”, which means “happiness” and is meant to symbolically express the Qiao family’s hope for a bright future. Some of its courtyards are flanked at their entrance by fearsome stone guardian lions, while others have their eaves delicately painted with tableaus of Chinese folk legends or their gates engraved with beautiful patterns.

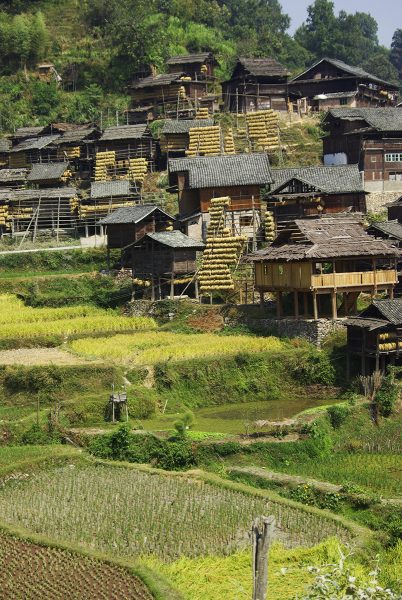

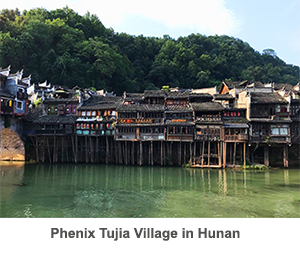

In contrast to the Miao people, the Tujia people prefer to live near mountains but close to or sometimes even over rivers or streams. Thus you’ll find that many Tujia diaojiaolou are either placed directly on the waterfront or hang over the water. The Tujia believe that these stilted houses embody the coexistence of God and man, so the designs of their diaojiaolou often reflect this. Tujia diaojiaolou are hard to come by, since the Tujia people are slowly abandoning their old settlements and assimilating into modern Chinese culture. The Tujia Folk Customs Park in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, is a large scale replica of a traditional Tujia village and features Tujia style Diaojiaolou. However, if you want a more authentic experience, we recommend visiting the Tujia village of Shuitianba in the Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hubei Province.

In contrast to the Miao people, the Tujia people prefer to live near mountains but close to or sometimes even over rivers or streams. Thus you’ll find that many Tujia diaojiaolou are either placed directly on the waterfront or hang over the water. The Tujia believe that these stilted houses embody the coexistence of God and man, so the designs of their diaojiaolou often reflect this. Tujia diaojiaolou are hard to come by, since the Tujia people are slowly abandoning their old settlements and assimilating into modern Chinese culture. The Tujia Folk Customs Park in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, is a large scale replica of a traditional Tujia village and features Tujia style Diaojiaolou. However, if you want a more authentic experience, we recommend visiting the Tujia village of Shuitianba in the Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hubei Province.

Although the archway, bell tower, drum tower, and shrine to Shakyamuni Buddha were all rebuilt during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the wooden tower itself is in its original condition and has been stunningly well-preserved. It stands on a 4 metre (13 ft.) high stone platform that is delicately decorated with crawling lion sculptures in the Liao Dynasty style, and it towers in at a height of over 67 metres (220 ft.). Looking at it from the outside, it appears to have only five storeys, but walk inside and you’ll soon realise that there are in fact nine storeys in total. Just when you thought you were going to have a relaxing climb to the top!

Although the archway, bell tower, drum tower, and shrine to Shakyamuni Buddha were all rebuilt during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the wooden tower itself is in its original condition and has been stunningly well-preserved. It stands on a 4 metre (13 ft.) high stone platform that is delicately decorated with crawling lion sculptures in the Liao Dynasty style, and it towers in at a height of over 67 metres (220 ft.). Looking at it from the outside, it appears to have only five storeys, but walk inside and you’ll soon realise that there are in fact nine storeys in total. Just when you thought you were going to have a relaxing climb to the top!

That is until the

That is until the

At its western point, Jinshanling is connected with Simatai and, together with Simatai, it is also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

At its western point, Jinshanling is connected with Simatai and, together with Simatai, it is also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Panlongshan or “Coiling Dragon Mountain” section of the Great Wall is the part of the Gubeikou section of the Great Wall that connects to the Jinshanling section.

The Panlongshan or “Coiling Dragon Mountain” section of the Great Wall is the part of the Gubeikou section of the Great Wall that connects to the Jinshanling section.

Huangyaguan or Huangya Pass was once one of the most important fortresses along the Great Wall. It was originally constructed during the Northern Qi Dynasty (550-577 AD), but the wall we see today is a result of major renovations that took place in 1569, during the Ming Dynasty, under the supervision of the renowned general Qi Jiguang.

Huangyaguan or Huangya Pass was once one of the most important fortresses along the Great Wall. It was originally constructed during the Northern Qi Dynasty (550-577 AD), but the wall we see today is a result of major renovations that took place in 1569, during the Ming Dynasty, under the supervision of the renowned general Qi Jiguang. The Baiyangyu section of the Great Wall is located in Qian’an of Hebei province, beginning at Da’ao Tower in the east and ending at the Laojuntai Terrace of the Sidaogou section in the west. It was originally constructed towards the beginning of the Ming Dynasty and was greatly enhanced during the dynasty’s later years. It stretches for a whopping 4,550 metres in length and includes 1,500 metres of marble walling, which is highly unusual when compared to other sections of the Great Wall. This marble section of the Great Wall is 10 metres high and 5 metres wide. Of the 21 towers that once guarded this section of the wall, 6 of them are still in good condition.

The Baiyangyu section of the Great Wall is located in Qian’an of Hebei province, beginning at Da’ao Tower in the east and ending at the Laojuntai Terrace of the Sidaogou section in the west. It was originally constructed towards the beginning of the Ming Dynasty and was greatly enhanced during the dynasty’s later years. It stretches for a whopping 4,550 metres in length and includes 1,500 metres of marble walling, which is highly unusual when compared to other sections of the Great Wall. This marble section of the Great Wall is 10 metres high and 5 metres wide. Of the 21 towers that once guarded this section of the wall, 6 of them are still in good condition.

Shanhai may be the “First Pass Under Heaven”, but Jiayu Pass is commonly referred to as the “First and Greatest Pass Under Heaven”. Talk about one-upmanship! It earned this title primarily because it was built around about 1372, during the early Ming Dynasty, and is one of the most well-preserved military buildings remaining along the Great Wall. It is located at the narrowest point along the western section of the Hexi Corridor in

Shanhai may be the “First Pass Under Heaven”, but Jiayu Pass is commonly referred to as the “First and Greatest Pass Under Heaven”. Talk about one-upmanship! It earned this title primarily because it was built around about 1372, during the early Ming Dynasty, and is one of the most well-preserved military buildings remaining along the Great Wall. It is located at the narrowest point along the western section of the Hexi Corridor in

The scenic village of Lucun is just one kilometre (0.6 mi) north of

The scenic village of Lucun is just one kilometre (0.6 mi) north of