According to legend, the Queen Mother of the West was holding her Flat Peach Carnival when she accidentally spilled some of her jade wine down from paradise, which caused a colossal flood here on earth. The flood destroyed all of the villages in the Huashan area so the deity Shaohao informed the Jade Emperor of the disaster. The Jade Emperor promptly sent the deity Juling to earth to stem the flood. As Juling descended from the clouds he rested his left hand on one side of the peak and his right leg on the other, which ripped the mountain into two halves and allowed the floodwater to rush out. His handprint supposedly remains on the Immortal’s Palm Peak, which sits high up on Mount Hua.

Standing at an impressive 2,100 metres (7,070 ft.) at its highest peak, it is no wonder that Mount Hua is listed as one of the Five Great Mountains of China. It is located approximately 120 kilometres east of Xi’an, near a city called Huayin. It sits at the eastern end of the Qin Mountains and is made up of five peaks. Although the mountain is undoubtedly a phenomenal natural specimen, it is more well-known in China for its spiritual and religious significance. Each of its five peaks has an intricately woven folktale behind it, which is intertwined with the Chinese mythology that is now known to be part legend and part historical fact. To the locals and to the average visitor, Mount Hua has an unmistakably mystical feel about it. If you’re looking for somewhere where you can embrace your spirituality and discover more about the fascinating schools of thought behind Chinese philosophy, then a trip to Mount Hua is a must.

The five main peaks of the mountain are simply named East Peak, South Peak, West Peak, Central Peak, and North Peak, with South Peak being the highest and North Peak being the lowest.

Every peak has inherited a second name according to its features or the legendary stories behind it.

Central Peak is known as Jade Maiden Peak. The story behind its name is a perfect example of how Chinese legend has become inseparably intertwined with history. There is a Taoist Temple at the top of this peak called the Jade Maiden Temple. Legend has it that the daughter of Duke Mu of Qin[1] (569 – 621 BC) loved a man who was talented at playing the tung-hsiao[2]. In order to avoid this temptation and cultivate her spirituality, she gave up the royal life she had become accustomed to and became a hermit, secreting herself on the Central Peak of Mount Hua. From then on, the temple was established and the peak was named Jade Maiden Peak after the Duke’s daughter. Near to the Jade Maiden Temple you will also find the Rootless Tree and the Sacrificing Tree, which also have mystical stories behind them that add to the ethereal feel of Central Peak.

Unfortunately not every story behind each peak is quite so magical. The South Peak is called Landing Wild Geese Peak simply because, according to legend, geese returning from the south often landed on this peak. It is home to the beautiful Black Dragon Pool and the Baidi Temple or Jintian Palace, a Taoist Temple that is nationally considered the host temple of the deity Shaohao. South Peak is also the site of the infamous Plank Road, a plank path built along the side of a vertical cliff that is only about 0.3 metres (about 1 foot) wide and forces the intrepid hiker to look down at the almost bottomless gulf below them. Although there is a chain running along the cliff-face that hikers can clip themselves on to, the experience of creeping along the narrow path and having to constantly hook and unhook yourself from your only safety net, so to speak, is only for the bravest of travellers.

Like South Peak, North Peak is rather simply named Cloud Terrace Peak because the clouds that accumulate around the peak look like a flat terrace. It looks so uncanny that you might get the impression you could almost step out onto the clouds. On one side of the peak is the Ear-Touching Cliff, which is so narrow that you supposedly have to press your ear to the cliff-face to climb it. Although this may seem like a joke, it is important to note that some of the paths on Mount Hua, such as the infamous Plank Road, are notoriously treacherous. The government has tried to put in as many safety measures as it can to make them safer but it is advised that you take the risks into careful consideration before venturing out onto the more dangerous paths. Historically there have been fatalities on these paths when visitors have not been careful or not heeded the warnings.

The West Peak is called the Lotus Flower Peak because there is a Taoist Temple there called Cuiyun Palace which has a huge rock in front of it that looks like a lotus flower. There are seven other rocks by Cuiyun Palace that are supposedly the site where the legendary hero Chenxiang ripped the mountain apart to save his mother, the Heavenly Goddess San Sheng Mu, in the folktale “The Magic Lotus Lantern”.

The East Peak, also known as Facing Sun Peak, is the best place to watch the sunrise and takes approximately 4 to 6 hours to climb. It is home to the famous Immortal’s Palm Peak mentioned earlier. Immortal Palm’s Peak is ranked as one of the Eight Scenic Wonders of the Guanzhong Area and is so-called because of the natural rock veins on the cliff, which look like a giant handprint and were supposedly caused by the deity Juling when he fell from heaven.

The East Peak, also known as Facing Sun Peak, is the best place to watch the sunrise and takes approximately 4 to 6 hours to climb. It is home to the famous Immortal’s Palm Peak mentioned earlier. Immortal Palm’s Peak is ranked as one of the Eight Scenic Wonders of the Guanzhong Area and is so-called because of the natural rock veins on the cliff, which look like a giant handprint and were supposedly caused by the deity Juling when he fell from heaven.

As early as the 2nd century B.C., it was recorded that a Taoist temple named the Shrine of the Western Peak rested at the base of the mountain. Taoists believed that the god of the underworld lived inside the mountain and this temple was used primarily by spirit mediums to contact this god and his underlings. Unlike Mount Taishan, which attracted many pilgrims, Mount Hua only seemed to attract Imperial pilgrims or local pilgrims due to its relative inaccessibility. Historically this earned it the reputation of being a retreat only for the hardiest of hermits, regardless of what religion they followed, as only those who were particularly strong-willed or spiritually enlightened could master the treacherous climb. Nowadays there are a number of temples and religious structures littered throughout the mountain, including a Taoist temple atop the Southern Peak that has been converted into a teahouse. At the foot of the mountain you’ll also find Xinyue Temple and the Jade Spring Temple. The sheer number of temples and religious constructions on and around the mountain demonstrate just how spiritually significant it is.

With all of the myths, history and spirituality behind it, Mount Hua has truly lived up to its reputation as one of the Five Great Mountains of China. When climbing the mountain and visiting the many temples on its peaks, you’re guaranteed not only beautiful scenic views but also a sense of spiritual calmness.

Xinyue Temple

Xinyue Temple rests at the bottom of Mount Hua. It was built to honour the god that is believed to live inside the mountain and was constructed during the reign of Emperor Wudi of the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 24 A.D.). Its stunning appearance and monumental size have earned it the name “The Forbidden City of Shaanxi Province”. Important scenic spots in Xinyue Temple include Haoling Gate, Five-Phoenix Pavilion, Lingxing Gate, Golden City Gate, Haoling Palace, the Emperor’s Study, and Longevity Pavilion. In the Five-Phoenix Pavilion there is a place called the Small Steles Forest where there are many impressive steles[3], including one of the most famous steles in the world: the Huashan Monument.

Xinyue Temple rests at the bottom of Mount Hua. It was built to honour the god that is believed to live inside the mountain and was constructed during the reign of Emperor Wudi of the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 24 A.D.). Its stunning appearance and monumental size have earned it the name “The Forbidden City of Shaanxi Province”. Important scenic spots in Xinyue Temple include Haoling Gate, Five-Phoenix Pavilion, Lingxing Gate, Golden City Gate, Haoling Palace, the Emperor’s Study, and Longevity Pavilion. In the Five-Phoenix Pavilion there is a place called the Small Steles Forest where there are many impressive steles[3], including one of the most famous steles in the world: the Huashan Monument.

The Jade Spring Temple (Yuquan Temple)

The Jade Spring Temple is a Taoist temple that rests at the foot of Mount Hua. Its main function is to hold Taoist activities and to allow its monks to practice Taoism. It was built by Jia Desheng during the Northern Song Dynasty (960 – 1127) to honour his teacher Chen Tuan[4] (871 – 989). Its name originates from a charming tale about a girl named the Golden Fairy Princess. Supposedly the Golden Fairy Princess was washing her hair beside the Jade Well on Mount Hua when she accidentally dropped her beautiful jade hair clasp into the well. She searched far and wide for her precious hair clasp but to no avail. Miraculously, as she was washing her hands with the spring water at the temple, she found her lost jade hair clasp. Since this spring was connected to the Jade Well, the princess decided to name the temple the Jade Spring Temple. Important scenic spots at this temple include the Long Corridor of Seventy-two Windows, which is a unique construction among Taoist temples across China.

[1] Duke Mu of Qin: He was the fourteenth ruler of the Zhou Dynasty State of Qin.

[2] Tsung-hsiao: A kind of Chinese flute that is held vertically rather than horizontally.

[3] Stele: An upright stone slab or pillar that bears an inscription and usually marks a burial site, like a tombstone.

[4] Chen Tuan: He was a famous scholar and hermit of the Quanzhen branch of Taoism. He helped to combine elements of Quietism, Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism, which greatly aided the development of neo-Confucianism.

Join our travel to challenge the Mount Hua: Explore the Silk Road in China and Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages

They have become renowned for a special type of building known as a Tulou, which can be found throughout southwest Fujian, Jiangxi, and Guangdong. These buildings are usually round or square in shape and can be several stories high. They are essentially fortresses and the larger ones resemble fortified villages! They were initially built to protect inhabitants from bandits and wild animals but are still in use today. After all, you never know when a marauding panda might come sniffing around! These earthen structures are considered so unique that a representative sample of about 10 Tulou in Fujian were made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008.

They have become renowned for a special type of building known as a Tulou, which can be found throughout southwest Fujian, Jiangxi, and Guangdong. These buildings are usually round or square in shape and can be several stories high. They are essentially fortresses and the larger ones resemble fortified villages! They were initially built to protect inhabitants from bandits and wild animals but are still in use today. After all, you never know when a marauding panda might come sniffing around! These earthen structures are considered so unique that a representative sample of about 10 Tulou in Fujian were made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008.

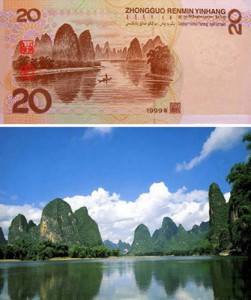

With its silvery beaches, sparkling waters, delectable array of seafood, and abundance of glittering pearls, once you get to Beihai you’ll never want to leave! Beihai is a tropical paradise nestled on the Gulf of Tonkin at the southernmost point of Guangxi. Its name literally means “north of the sea” because that’s precisely where it is. Two thousand years ago, Beihai was one of the main ports of the Maritime Silk Road, providing Guangxi, Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Hunan, and Hubei with access to foreign trade. Nowadays it provides foreign tourists with an opportunity to marvel at the aquatic wildlife, work on their tans, or sample some of the freshest seafood in Guangxi. If only they could export such wonderful products!

With its silvery beaches, sparkling waters, delectable array of seafood, and abundance of glittering pearls, once you get to Beihai you’ll never want to leave! Beihai is a tropical paradise nestled on the Gulf of Tonkin at the southernmost point of Guangxi. Its name literally means “north of the sea” because that’s precisely where it is. Two thousand years ago, Beihai was one of the main ports of the Maritime Silk Road, providing Guangxi, Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Hunan, and Hubei with access to foreign trade. Nowadays it provides foreign tourists with an opportunity to marvel at the aquatic wildlife, work on their tans, or sample some of the freshest seafood in Guangxi. If only they could export such wonderful products!

The East Peak, also known as Facing Sun Peak, is the best place to watch the sunrise and takes approximately 4 to 6 hours to climb. It is home to the famous Immortal’s Palm Peak mentioned earlier. Immortal Palm’s Peak is ranked as one of the Eight Scenic Wonders of the Guanzhong Area and is so-called because of the natural rock veins on the cliff, which look like a giant handprint and were supposedly caused by the deity Juling when he fell from heaven.

The East Peak, also known as Facing Sun Peak, is the best place to watch the sunrise and takes approximately 4 to 6 hours to climb. It is home to the famous Immortal’s Palm Peak mentioned earlier. Immortal Palm’s Peak is ranked as one of the Eight Scenic Wonders of the Guanzhong Area and is so-called because of the natural rock veins on the cliff, which look like a giant handprint and were supposedly caused by the deity Juling when he fell from heaven. Xinyue Temple rests at the bottom of Mount Hua. It was built to honour the god that is believed to live inside the mountain and was constructed during the reign of Emperor Wudi of the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 24 A.D.). Its stunning appearance and monumental size have earned it the name “The Forbidden City of Shaanxi Province”. Important scenic spots in Xinyue Temple include Haoling Gate, Five-Phoenix Pavilion, Lingxing Gate, Golden City Gate, Haoling Palace, the Emperor’s Study, and Longevity Pavilion. In the Five-Phoenix Pavilion there is a place called the Small Steles Forest where there are many impressive steles

Xinyue Temple rests at the bottom of Mount Hua. It was built to honour the god that is believed to live inside the mountain and was constructed during the reign of Emperor Wudi of the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 24 A.D.). Its stunning appearance and monumental size have earned it the name “The Forbidden City of Shaanxi Province”. Important scenic spots in Xinyue Temple include Haoling Gate, Five-Phoenix Pavilion, Lingxing Gate, Golden City Gate, Haoling Palace, the Emperor’s Study, and Longevity Pavilion. In the Five-Phoenix Pavilion there is a place called the Small Steles Forest where there are many impressive steles