Qinghai is located far to the northwest and is the fourth largest province in China. Yet, with a population of just 5.2 million, it is the third least populated province in the country. To put that into perspective, it covers an area larger than the country of France but only has about a thirteenth of the population. So, if you fancy some serious alone time, Qinghai is the place to be! It is named after the resident Qinghai Lake, the largest lake in China, but is occasionally referred to by its alternate name of Kokonor.

It is bordered by Gansu in the northeast, Xinjiang in the northwest, Sichuan in the southeast, and the Tibet Autonomous Region in the southwest. This, coupled with its location on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau, means it has long been a melting pot for various nomadic cultures. Nowadays, though the Han people still represent the majority, the province is home to 37 of China’s recognised ethnic minorities, with large constituencies of Tibetan, Hui, Tu, Mongol, and Salar people. With 5 out of its 8 prefectures being designated as Tibetan autonomous regions, the province itself is noticeably dominated by Tibetan culture.

Qinghai’s main claim to fame is its wonderful scenery and diverse landscapes. In the north, the snowy Altun and Qilian mountains rise up and form a protective barrier along the sparsely populated northern border. The magnificent Kunlun Mountains strike through the centre of the province while the Tanggula Mountains in the south represent the point where the Yangtze River begins. So be sure to pack your hiking boots, or you’ll end up with some pretty sore feet!

The province is home to the headwaters of three major rivers: the Yellow, Yangtze, and Mekong rivers. Qinghai is thus renowned as a paradise of rolling hills, snowy mountains, verdant grasslands, and rushing waters. Over 250 of its animal species are under national protection, including the wild camel, Tibetan antelope, white-lipped deer, snow leopard, and yak.

Since Qinghai rests at a relatively high altitude compared to other provinces, it experiences cold winters, mild summers, and huge variations in daily temperature. In January, temperatures can plummet to between −7 and −18 °C (19 to 0 °F), while in July they raise to a modest 15 to 21 °C (59 to 70 °F). From February to April, the region is plagued by heavy winds that blow in sandstorms from the Gobi Desert, so avoid this season unless you want to end up looking like Lawrence of Arabia!

During summer, domestic tourists flock to the provincial capital of Xining to enjoy the temperate and balmy weather. The comfortable temperatures throughout July and August, coupled with the relative lack of humidity, make Xining an ideal summer retreat. It’s also home to the Dongguan Mosque, which has been continuously operating since 1380 and is the largest mosque in the province.

During summer, domestic tourists flock to the provincial capital of Xining to enjoy the temperate and balmy weather. The comfortable temperatures throughout July and August, coupled with the relative lack of humidity, make Xining an ideal summer retreat. It’s also home to the Dongguan Mosque, which has been continuously operating since 1380 and is the largest mosque in the province.

That being said, the province’s star attraction is undoubtedly Qinghai or “Cyan Sea” Lake, which is surrounded by misty mountains, lush meadows, and communities of fascinating Tibetan people. There are several islands on the lake that are open to tourists, including Bird Island, Haixin Mountain, and Sand Island. For nature lovers, the Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve and the Kekexili State Nature Reserve are idyllic locations divorced from man’s influence. The former is the location of the headwaters for the Yellow, Yangtze, and Mekong rivers, while the latter is home to a large community of precious Tibetan antelope.

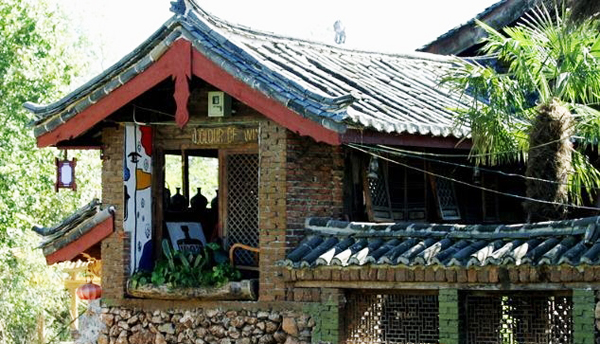

In terms of Qinghai’s religious significance, the Kumbum Monastery in Huangzhong City was founded in 1583 and is the most prestigious “gompa” or Buddhist university monastery after the “great three” gompa of Tibet; Drepung Monastery, Ganden Monastery, and Sera Monastery. The Gyanak Mani Temple just outside of Yushu City boasts the country’s largest collection of carved prayer stones, with over 2 billion of the stones neatly stacked in an area of just 1 square kilometre (0.4 sq. mi). In a place this sacred, be sure to expect a stony silence!

The preserve is home to many animals that are currently under national protection, such as snow leopards, Tibetan antelope, golden eagles, and brown bears. Thus the region is precious not only for its natural beauty, but for the many endangered species that inhabit its plains. Unlike other mountainous areas in China, the region is densely covered with lakes, such as Kekexili Lake, Sun Lake and Xuelian Lake, meaning that its animal residents are never too far away from a good drink and a good meal. Unfortunately, if you’re a cuddly little plateau pika

The preserve is home to many animals that are currently under national protection, such as snow leopards, Tibetan antelope, golden eagles, and brown bears. Thus the region is precious not only for its natural beauty, but for the many endangered species that inhabit its plains. Unlike other mountainous areas in China, the region is densely covered with lakes, such as Kekexili Lake, Sun Lake and Xuelian Lake, meaning that its animal residents are never too far away from a good drink and a good meal. Unfortunately, if you’re a cuddly little plateau pika