Flanked by the Qilian Mountains to the north and split by the Yellow River at its centre, Lanzhou is a city immersed in its natural surroundings. It is the provincial capital of Gansu province and historically was one of the major trading cities along the ancient Silk Road. With the Maijishan Grottoes to its east, Bingling Temple Grottoes to its west, Labrang Monastery to its south, and Mogao Caves to its north, Lanzhou delivers magnificent historical attractions at every point of the compass!

The city rests deep with the Hexi Corridor, which was a natural passageway that connected China with Central Asia and was thus an integral part of the Silk Road. This corridor was flanked by the misty Qilian Mountains and Tibetan Plateau in the south and the Beishan Mountains and inhospitable Gobi Desert in the north, meaning trading caravans really only had one choice when it came to traveling into China. This made control of the Hexi Corridor invaluable, as whoever controlled this territory would also have power over one of the most important trade routes in world history. This meant that, like a prime piece of real estate, oases towns along the Hexi Corridor were hotly contested!

The Lanzhou region originally belonged to the Western Qiang people, but became part of the State of Qin during the 6th century BC. Under the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), it became one of the major links along the Silk Road and was also an important crossing point on the Yellow River. It was considered so valuable that it eventually earned the nickname the Golden City! The stunning Yumen Pass and Yang Pass, two of the last surviving earthen portions of the Great Wall, were erected during this time as part of a huge section of wall stretching along the northern frontier. This was designed by the Han court to help defend the Silk Road from northern invaders such as the Xiongnu people, and achieved relative success until the collapse of the Han Dynasty. Thereafter the region was passed around between several tribal states faster than a hot potato!

During the 4th century, Lanzhou briefly became the capital of the Former Liang Dynasty (320–376), until it was conquered by the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535). Under the guidance of the Northern Wei rulers, the city flourished as a centre for Buddhist study from the 5th right through until the 11th century. It was recaptured by Chinese forces during the Sui Dynasty (581-618), where it became the seat of Lanzhou prefecture, but during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) it was lost to the Tibetans in 763 and wasn’t recovered until 843. However this imperial control turned out to be just another brief flirtation, as it soon fell into the hands of the Tangut people, who established the Western Xia Dynasty (1038–1227).

The Song Dynasty (960-1279) were able to take back the region and rename it Lanzhou in 1041, but it was once again lost in 1127 to the Jurchen people of the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234). It seemed that, when it came to being held, Lanzhou was as slippery as an eel! It was finally incorporated into the Mongol Empire (1206–1368) in 1235 and remained part of China proper from the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) onwards.

Evidence of the city’s illustrious history as a centre for Buddhism can be found just 80 kilometres (50 mi) to its southwest in the form of the Bingling Temple Grottoes or Thousand Buddha Caves. This sequence of caves was begun sometime during the 4th century and construction continued for approximately 1,000 years, yielding over 200 caves, 690 stone statues, 82 clay sculptures, and some 900 square metres (9,700 sq. ft.) of stunning murals. It’s a veritable treasure trove of ancient Buddhist art but its isolated location means that, unlike the Mogao Caves and the Maijishan Grottoes, it receives very little tourist traffic and makes for a peaceful day out. You may even come back from your trip a little more enlightened!

Other Buddhist relics to be found in the city include the temples at the Five Spring Mountain Park on the northern side of Gaolan Mountain. According to legend, a famous Han general named Huo Qubing once led his forces here, where they nearly collapsed from exhaustion and thirst. Without further ado, Huo whipped the ground five times with his trusty horsewhip and five springs appeared. These springs can still be seen today and are dotted about amongst the numerous architectural sites, including the Butterfly Pavilion, Dizang Temple, and Wenchang Palace.

Other Buddhist relics to be found in the city include the temples at the Five Spring Mountain Park on the northern side of Gaolan Mountain. According to legend, a famous Han general named Huo Qubing once led his forces here, where they nearly collapsed from exhaustion and thirst. Without further ado, Huo whipped the ground five times with his trusty horsewhip and five springs appeared. These springs can still be seen today and are dotted about amongst the numerous architectural sites, including the Butterfly Pavilion, Dizang Temple, and Wenchang Palace.

And, if it’s historical architecture you’re after, then no trip to Lanzhou would be complete without a visit to Zhongshan Bridge. This was once the site of Zhen Yuan Floating Bridge, one of the many floating bridges that spanned the Yellow River. These bridges were formed by strapping over 20 ships together using ropes and chains. Now this may sound rather magical, but these bridges were notoriously unstable and were frequently destroyed by floods, resulting in the death of many people. That being said, like Rocky Balboa, it seems Zhen Yuan Bridge wasn’t going to retire without a fight! In spite of adversity, it managed to survive for a staggering 500 years before it was finally replaced in 1909 by the iron Zhongshan Bridge you see today.

Join a travel with us to explore more about Lanzhou: Explore “The Good Earth” in Northwest China

Danxia Landforms, named after Mount Danxia in Guangdong province, are stunning geological formations that are unique to China. They were formed when red sandstone and other minerals were deposited by rivers over a period of about 24 million years. These deposits settled into distinct layers and, after another 15 million years, faults in the earth created by tectonic plate movement caused them to become exposed. Over another few millions of years, they were moulded into strange shapes by weathering and erosion, resulting in the unusual landforms that we find today. Yet the ones near Zhangye are arguably the most spectacular as, rather than just being made up of fiery red sandstone, the hills are a flurry of vibrant colours that resemble a living watercolour painting. For this reason, they have earned the nickname the “Rainbow Mountains”.

Danxia Landforms, named after Mount Danxia in Guangdong province, are stunning geological formations that are unique to China. They were formed when red sandstone and other minerals were deposited by rivers over a period of about 24 million years. These deposits settled into distinct layers and, after another 15 million years, faults in the earth created by tectonic plate movement caused them to become exposed. Over another few millions of years, they were moulded into strange shapes by weathering and erosion, resulting in the unusual landforms that we find today. Yet the ones near Zhangye are arguably the most spectacular as, rather than just being made up of fiery red sandstone, the hills are a flurry of vibrant colours that resemble a living watercolour painting. For this reason, they have earned the nickname the “Rainbow Mountains”.

The 70 caves that make up the complex were hand-carved into the cliff-face of Linsong Mountain, about 65 kilometres (40 mi) north of Zhangye, and can be separated into 7 grotto groups: Mati Temple, Shenguo Temple, Qianfo or “Thousand Buddha” Caves, Jinta or “Golden Tower” Temple, Upper Guanyin Cave, Middle Guanyin Cave, and Lower Guanyin Cave.

The 70 caves that make up the complex were hand-carved into the cliff-face of Linsong Mountain, about 65 kilometres (40 mi) north of Zhangye, and can be separated into 7 grotto groups: Mati Temple, Shenguo Temple, Qianfo or “Thousand Buddha” Caves, Jinta or “Golden Tower” Temple, Upper Guanyin Cave, Middle Guanyin Cave, and Lower Guanyin Cave. With the snow-capped Qilian Mountains behind and the jade-hued grasslands stretching out in front, the scenery surrounding the Mati Temple is unparalleled in its natural beauty. It rests just outside of a small village that is also conveniently named Mati. It seems those hoof-prints really made their mark after all! Since the village is populated primarily by members of the Yugur ethnic minority, visitors to the area are also welcome to indulge in a few Yugur customs. From enjoying a cup of pure chang, a locally brewed wine made from barley, to sampling sumptuous chunks of traditional stewed lamb, you won’t want to miss out on a chance to connect with these gentle, nomadic people. If you want to extend your stay, you can even spend a few days in one of their yurts and take part in a few horse rides. Just don’t walk behind the horses, or you may end up with a sacred hoof-print on your head!

With the snow-capped Qilian Mountains behind and the jade-hued grasslands stretching out in front, the scenery surrounding the Mati Temple is unparalleled in its natural beauty. It rests just outside of a small village that is also conveniently named Mati. It seems those hoof-prints really made their mark after all! Since the village is populated primarily by members of the Yugur ethnic minority, visitors to the area are also welcome to indulge in a few Yugur customs. From enjoying a cup of pure chang, a locally brewed wine made from barley, to sampling sumptuous chunks of traditional stewed lamb, you won’t want to miss out on a chance to connect with these gentle, nomadic people. If you want to extend your stay, you can even spend a few days in one of their yurts and take part in a few horse rides. Just don’t walk behind the horses, or you may end up with a sacred hoof-print on your head!

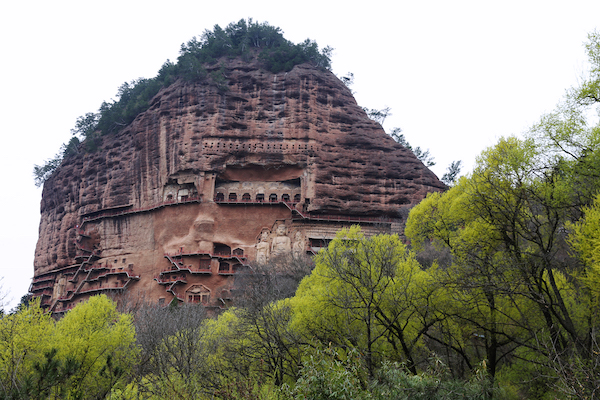

The mountain itself sits at an altitude of 1,700 metres (5,577 ft.) and is named “Maiji”, meaning “wheat”, “corn”, or “grain stack”, due to its unusual appearance. It is tall in the middle, narrow at the bottom, and completely flat on the top, meaning it resembles a stack of wheat. So be careful when you take photographs of this scenic spot, or they might come out a little grainy! The caves are separated by number, with numbers 1 to 50 on the western cliff-face and numbers 51-191 on the eastern cliff-face.

The mountain itself sits at an altitude of 1,700 metres (5,577 ft.) and is named “Maiji”, meaning “wheat”, “corn”, or “grain stack”, due to its unusual appearance. It is tall in the middle, narrow at the bottom, and completely flat on the top, meaning it resembles a stack of wheat. So be careful when you take photographs of this scenic spot, or they might come out a little grainy! The caves are separated by number, with numbers 1 to 50 on the western cliff-face and numbers 51-191 on the eastern cliff-face. Construction of the grottoes reached its peak during the Northern Wei (386-535), Western Wei (535–557), and Northern Zhou (557-581) dynasties, but continued well into the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, representing over 1,000 years’ worth of effort and artistry. The earlier caves are far more simplistic in design and mainly feature a seated Buddha flanked by bodhisattvas

Construction of the grottoes reached its peak during the Northern Wei (386-535), Western Wei (535–557), and Northern Zhou (557-581) dynasties, but continued well into the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, representing over 1,000 years’ worth of effort and artistry. The earlier caves are far more simplistic in design and mainly feature a seated Buddha flanked by bodhisattvas The bodhisattvas who usually accompany Amitābha are Avalokitesvara on his right and Mahasthamaprapta on his left. Avalokitesvara is the most identifiable, as he is typically depicted with an image of Amitābha on his headdress and a small water flask in his hands. In a few more hundred years, Avalokitesvara will change genders and eventually reappear in the grottoes as the bodhisattva of mercy, known as Guanyin. That being said, when it comes to eternal enlightenment, it doesn’t really matter if you’re a man or a woman! Other statues include those of the historical Shakyamuni

The bodhisattvas who usually accompany Amitābha are Avalokitesvara on his right and Mahasthamaprapta on his left. Avalokitesvara is the most identifiable, as he is typically depicted with an image of Amitābha on his headdress and a small water flask in his hands. In a few more hundred years, Avalokitesvara will change genders and eventually reappear in the grottoes as the bodhisattva of mercy, known as Guanyin. That being said, when it comes to eternal enlightenment, it doesn’t really matter if you’re a man or a woman! Other statues include those of the historical Shakyamuni

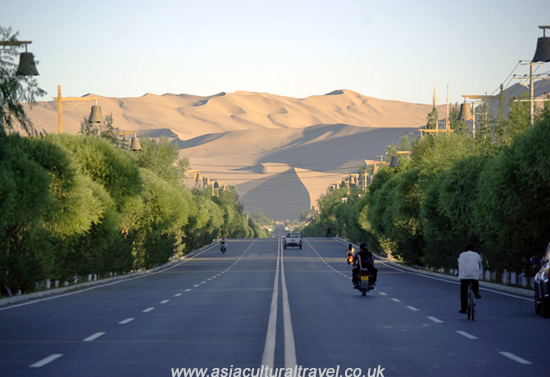

China owns the largest distribution of yardangs in the world and, of these, Dunhuang Yardang National Geopark contains the lion’s share. Exhibiting over 300 square kilometres (116 sq. mi) of yardangs, it covers an area over 100 times the size of the city of London! It’s rumoured that, if you use your imagination, some of these them begin to look like famous world sites, such as the Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Pyramids of Egypt. That being said, to you they may all just look like rocks!

China owns the largest distribution of yardangs in the world and, of these, Dunhuang Yardang National Geopark contains the lion’s share. Exhibiting over 300 square kilometres (116 sq. mi) of yardangs, it covers an area over 100 times the size of the city of London! It’s rumoured that, if you use your imagination, some of these them begin to look like famous world sites, such as the Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Pyramids of Egypt. That being said, to you they may all just look like rocks!