At the southern foot of the Wuzhou Mountains, deep within the Shi Li River Valley, the Yungang Grottoes stretch for over a kilometre and are etched indelibly into the rock-face. Just 16 kilometres west of Datong City, this group of 53 caves, 252 grottoes, and over 51,000 statues and statuettes have inspired visitors from all religious backgrounds for centuries.

They were carved sometime between 453 and 525 AD, during the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534 AD), and are categorised as one of the “Four Grand Groups of Grottoes” in China. The grottoes combine features from traditional Chinese art with those from foreign art styles, such as Greek and Indian, while the statues themselves range in height from 2 centimetres (0.7 in.) to 17 metres (56 ft.). So if you thought you were short, imagine being a thimble-sized statue next to one the size of an oak tree!

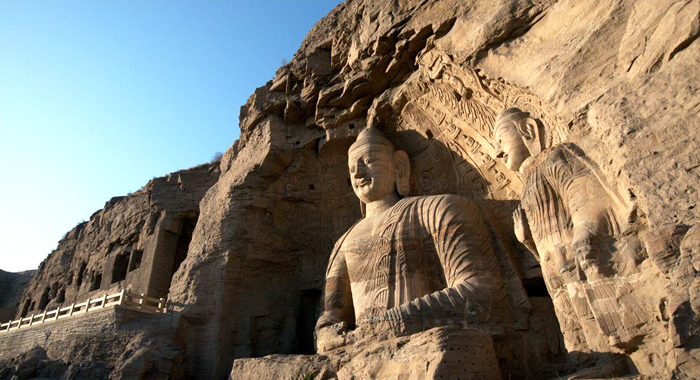

Unsurprisingly the grottoes were listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 2001 and are currently divided into three major groups open to the public: the east section (caves 1-4); the central section (caves 5-13); and the west section (caves 14-53). Cave No. 6 is the largest, with a height of about 20 metres (65 ft.), but it is Cave No. 5 that contains the exemplary 17-metre-tall statue of Buddha. Unfortunately, over a period of more than 1,500 years, many of the statues have been damaged by war, pollution, and natural disasters, so parts of the complex are periodically shut down for maintenance. After all, at the grand old age of 1,500, they certainly deserve a little face lift every now and then!

Unsurprisingly the grottoes were listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 2001 and are currently divided into three major groups open to the public: the east section (caves 1-4); the central section (caves 5-13); and the west section (caves 14-53). Cave No. 6 is the largest, with a height of about 20 metres (65 ft.), but it is Cave No. 5 that contains the exemplary 17-metre-tall statue of Buddha. Unfortunately, over a period of more than 1,500 years, many of the statues have been damaged by war, pollution, and natural disasters, so parts of the complex are periodically shut down for maintenance. After all, at the grand old age of 1,500, they certainly deserve a little face lift every now and then!

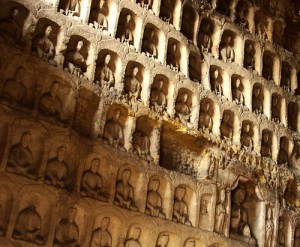

The construction of the grottoes can be split into three time periods: the Early Period (460-465 AD); the Middle Period (c. 471-494); and the Late Period (494-525). Those constructed in the Early Period are considered the most magnificent and contain the five main caves masterminded by the revered monk Tan Yao (caves 16-20). These particular caves are between 13 to 15 metres in height and are generally U-shaped with an arched roof, imitating the thatched sheds that were prolific in ancient India. Each cave has a door and a window, while the main part of the cave is taken up with the central statue and the walls are bedecked with carvings of thousands of smaller Buddhist statuettes. Just imagine all of those tiny eyes staring down at you!

Throughout the Middle Period, the artistic style became more traditionally Chinese and the caves themselves reflect the hall arrangement that was popularised during the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). By the Late Period, the caves and statues had become much smaller in size and simpler in style, giving them a certain stately elegance. Perhaps they’d come to the realisation that, when it comes to spiritual enlightenment, size doesn’t matter!

The history of the Yungang Grottoes is inextricably tied with that of the Northern Wei Dynasty. After the fall of the Jin Dynasty (265-420), a Turkic nomadic tribe known as the Tuoba clan took control of northern China and established their own dynasty. With the exception of Emperor Taiwu, the Tuoba clan were devout Buddhists, predominantly for political reasons as the religion helped them maintain control of their territory. Sometime between 398 and 494, Emperor Xiaowen established Pingcheng (modern-day Datong) as their capital and it would remain this way until 523, when Pingcheng would be abandoned due to warfare.

Originally the emperor only commissioned five caves, to be built by Tan Yao and to depict the first five Wei emperors in Buddhist forms or as Buddha. These are now known as caves number 16 to 20 and were completed in 465 AD. From 471 to 494 the second phase of construction began and it is thought that caves 5 through 13 were built during this time. All of these grottoes were built under imperial patronage, but that unfortunately ended when the Wei court abandoned Pingcheng and moved their capital to Luoyang. In short, like water in the surrounding sands, the money dried up! All of the caves built after 494 are thought to have been financed privately, which may explain why they’re so small!

Originally the emperor only commissioned five caves, to be built by Tan Yao and to depict the first five Wei emperors in Buddhist forms or as Buddha. These are now known as caves number 16 to 20 and were completed in 465 AD. From 471 to 494 the second phase of construction began and it is thought that caves 5 through 13 were built during this time. All of these grottoes were built under imperial patronage, but that unfortunately ended when the Wei court abandoned Pingcheng and moved their capital to Luoyang. In short, like water in the surrounding sands, the money dried up! All of the caves built after 494 are thought to have been financed privately, which may explain why they’re so small!

During the Liao Dynasty (907-1125), wooden structures were built in front of the grottoes in an attempt to shield them from weather damage and incorporate them into temples. These were known as the Ten Famous Temples but were tragically destroyed due to warfare in 1122. The stunning wooden temples that can be found in front of caves 5, 6, and 7 were built for a similar purpose during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) but appear to have survived intact. From the 1950s onwards, numerous restorations and preservation projects have been implemented to protect the grottoes from further damage.

The Yungang Grottoes is one of the many wonderful stops on our Cultural Tour in Shanxi.

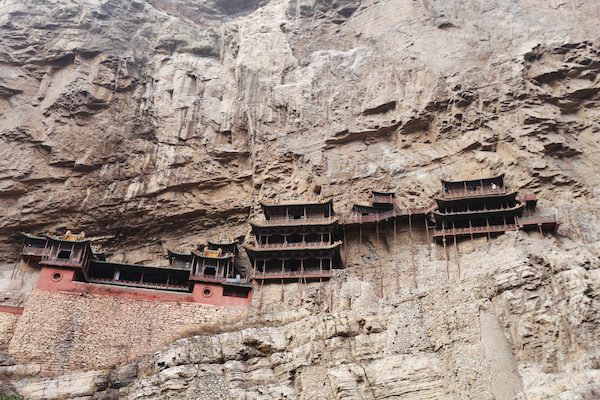

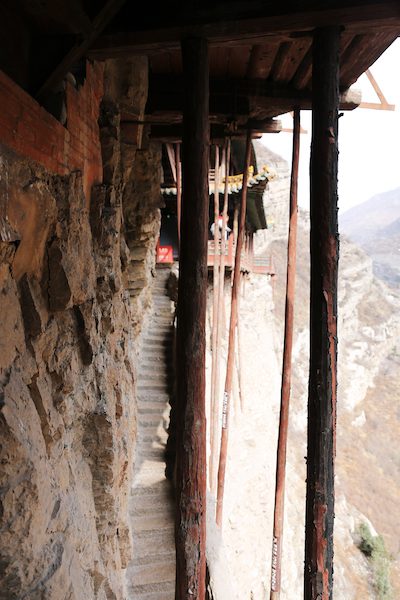

No one knows precisely who built the temple or who organised its construction, but many historians believe it was likely to have been masterminded by the King of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534 AD). However, according to one local legend, the original temple was built by a single monk named Liao Ran. Either he must have been very tall or very brave! The temple has undergone several rebuilds and restorations throughout the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties to achieve its current glory. The temple complex itself is made up of 40 halls containing around 80 sculptures of copper, iron, terracotta, and stone. A stone staircase chiselled deep into the rock allows access to the temple, while the 6 main halls are connected by staircases, walkways, and boardwalks that provide a dizzying view of the drop below. Just don’t look down!

No one knows precisely who built the temple or who organised its construction, but many historians believe it was likely to have been masterminded by the King of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534 AD). However, according to one local legend, the original temple was built by a single monk named Liao Ran. Either he must have been very tall or very brave! The temple has undergone several rebuilds and restorations throughout the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties to achieve its current glory. The temple complex itself is made up of 40 halls containing around 80 sculptures of copper, iron, terracotta, and stone. A stone staircase chiselled deep into the rock allows access to the temple, while the 6 main halls are connected by staircases, walkways, and boardwalks that provide a dizzying view of the drop below. Just don’t look down! After entering the temple gate, you will arrive at the main building, which is made up of three floors. The upper floor hosts the Three Buddha Hall, the Taiyi Hall, the Guandi Hall, and four side rooms with intricate statues of Bodhisattvas. Behind the main building, there are two “flying buildings”, which are so-called because the top floors are connected to the main building by a narrow wooden walkway and the bottom floors are linked by a narrow path that has been dug into the cliff-face. From the bottom to the top, the southern building contains the Chunyang Hall, the Sanguan Hall, and the Leiyin Hall. The northern building consists of the Four Buddha Hall, the Sansheng Hall, and the Sanjiao Hall respectively.

After entering the temple gate, you will arrive at the main building, which is made up of three floors. The upper floor hosts the Three Buddha Hall, the Taiyi Hall, the Guandi Hall, and four side rooms with intricate statues of Bodhisattvas. Behind the main building, there are two “flying buildings”, which are so-called because the top floors are connected to the main building by a narrow wooden walkway and the bottom floors are linked by a narrow path that has been dug into the cliff-face. From the bottom to the top, the southern building contains the Chunyang Hall, the Sanguan Hall, and the Leiyin Hall. The northern building consists of the Four Buddha Hall, the Sansheng Hall, and the Sanjiao Hall respectively. The prevalence of religion in ancient China meant that travellers were reluctant to stay in temples that worshipped religions different from their own. Some theories about why the Hanging Temple enshrined three of China’s major religions was to encourage travellers of all kinds to stay there, as its remote location meant that any weary traveller who passed up the opportunity might not make it to the next safe haven. After all, we may have different religious beliefs, but we all get hungry and tired after a long trip!

The prevalence of religion in ancient China meant that travellers were reluctant to stay in temples that worshipped religions different from their own. Some theories about why the Hanging Temple enshrined three of China’s major religions was to encourage travellers of all kinds to stay there, as its remote location meant that any weary traveller who passed up the opportunity might not make it to the next safe haven. After all, we may have different religious beliefs, but we all get hungry and tired after a long trip!

Sorghum Fish (高粱面鱼鱼)

Sorghum Fish (高粱面鱼鱼) He asked the old boatman for some food, and the boatman replied: “All I have is some flour, but I don’t have a rolling pin to make noodles for you”. The boatman’s daughter looked down at the little kitten in her arms and swiftly thought of an idea. She began making the noodles by hand and used her fingers to create small indents in each noodle. Once they were finished, the old boatman cooked them and served them to the Emperor with a simple sauce. The Emperor was overwhelmed by how tasty the noodles were and, when he asked the boatman’s daughter what she wished to call the dish, she decided on “Cat’s Ear Noodles”. When the Emperor returned to his palace, he hired her to be his chef and, from that day onwards, her family wanted for nothing. What a purr-fect ending!

He asked the old boatman for some food, and the boatman replied: “All I have is some flour, but I don’t have a rolling pin to make noodles for you”. The boatman’s daughter looked down at the little kitten in her arms and swiftly thought of an idea. She began making the noodles by hand and used her fingers to create small indents in each noodle. Once they were finished, the old boatman cooked them and served them to the Emperor with a simple sauce. The Emperor was overwhelmed by how tasty the noodles were and, when he asked the boatman’s daughter what she wished to call the dish, she decided on “Cat’s Ear Noodles”. When the Emperor returned to his palace, he hired her to be his chef and, from that day onwards, her family wanted for nothing. What a purr-fect ending!

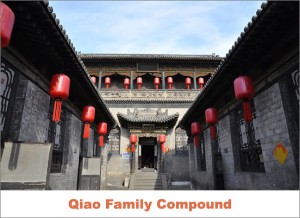

In 1900, the Eight-Nation Alliance sent troops to liberate their embassy in Beijing, which had been under siege as part of the violent Boxer Rebellion. Once they had resolved the issue with the embassy, they decided to invade and occupy the city of Beijing. In response, the governor-general of Shanxi province ordered that all foreigners in the region were to be killed on site. Seven Italian sisters, who were working in the country as missionaries, managed to escape the ensuing panic and eventually arrived at the Qiao Family Compound. They begged Qiao Zhiyong for protection and he accepted their plea.

In 1900, the Eight-Nation Alliance sent troops to liberate their embassy in Beijing, which had been under siege as part of the violent Boxer Rebellion. Once they had resolved the issue with the embassy, they decided to invade and occupy the city of Beijing. In response, the governor-general of Shanxi province ordered that all foreigners in the region were to be killed on site. Seven Italian sisters, who were working in the country as missionaries, managed to escape the ensuing panic and eventually arrived at the Qiao Family Compound. They begged Qiao Zhiyong for protection and he accepted their plea.

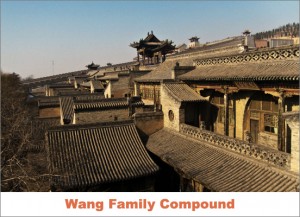

Nowadays, only two of the colossal courtyards and one of the ancestral halls are open to tourists, comprising a total of 123 smaller courtyards and over 1,100 rooms. The complex has been separated into three main areas: the Red Gate Castle; the Gao Jia Ya; and the Chongning Bao. Much like the Qiao Family Compound, these majestic halls have been transformed into exhibitions featuring artwork, calligraphy, sculptures, and other items that once belonged to the family. On August 18th of every year, a Tourism Festival is held in the Wang Family Compound, where visitors have the opportunity to watch and take part in traditional folk activities. It’s the ideal time to embrace the ancient culture in which this grand work of architecture was conceived.

Nowadays, only two of the colossal courtyards and one of the ancestral halls are open to tourists, comprising a total of 123 smaller courtyards and over 1,100 rooms. The complex has been separated into three main areas: the Red Gate Castle; the Gao Jia Ya; and the Chongning Bao. Much like the Qiao Family Compound, these majestic halls have been transformed into exhibitions featuring artwork, calligraphy, sculptures, and other items that once belonged to the family. On August 18th of every year, a Tourism Festival is held in the Wang Family Compound, where visitors have the opportunity to watch and take part in traditional folk activities. It’s the ideal time to embrace the ancient culture in which this grand work of architecture was conceived.

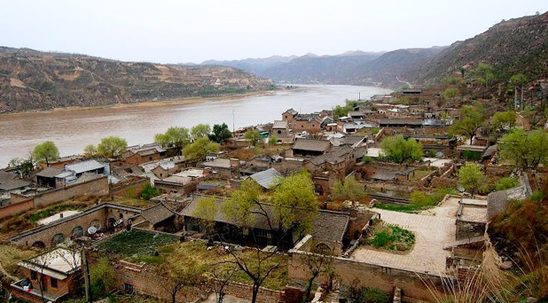

Although it may no longer be the glorious trade port it once was, Qikou is still a picturesque ancient town with many historic buildings that have been beautifully preserved. In order to protect them from flooding, many of these houses, known as “yaodongs” or “loess cave houses,” have been physically carved into the steep hillside along the banks of the Yellow River. Looming over these houses on a raised platform, the Black Dragon Temple is the ideal place to enjoy a panoramic view of town. The temple is dedicated primarily to two separate deities: the legendary Black Dragon; and Guan Yu, a military general from the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280) who was eventually deified.

Although it may no longer be the glorious trade port it once was, Qikou is still a picturesque ancient town with many historic buildings that have been beautifully preserved. In order to protect them from flooding, many of these houses, known as “yaodongs” or “loess cave houses,” have been physically carved into the steep hillside along the banks of the Yellow River. Looming over these houses on a raised platform, the Black Dragon Temple is the ideal place to enjoy a panoramic view of town. The temple is dedicated primarily to two separate deities: the legendary Black Dragon; and Guan Yu, a military general from the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280) who was eventually deified.

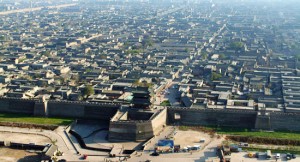

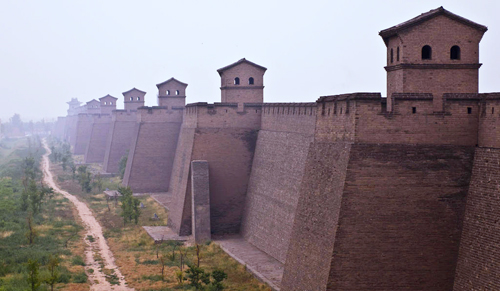

The walls are punctuated by six barbican gates in total, with one each on the north and south sides, and two each on the west and east sides. From an aerial perspective, this supposedly makes Pingyao look like a tortoise, with the west and east gates as the legs, the north gate as the tail, the south gate as the head, and the criss-crossing lanes within as the patterns on its shell. This has earned it the nickname the “Tortoise City”!

The walls are punctuated by six barbican gates in total, with one each on the north and south sides, and two each on the west and east sides. From an aerial perspective, this supposedly makes Pingyao look like a tortoise, with the west and east gates as the legs, the north gate as the tail, the south gate as the head, and the criss-crossing lanes within as the patterns on its shell. This has earned it the nickname the “Tortoise City”!

Alongside the city walls and Rishengchang, the other major attractions within the ancient city are the County Government Office and the Temple of the City God. While the County Government Office was designed to rule the “yang” of the human world, the Temple of the City God held sway over the “yin” of the spiritual world. These two buildings were placed on the same street in order to balance each other out, with the office in the west and the temple in the east. The County Government Office was originally built in 1346, during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), and is the largest of its kind in China. It represented a vast complex containing the home of the local magistrate, various offices, a prison, a court, meeting rooms, and a scenic garden.

Alongside the city walls and Rishengchang, the other major attractions within the ancient city are the County Government Office and the Temple of the City God. While the County Government Office was designed to rule the “yang” of the human world, the Temple of the City God held sway over the “yin” of the spiritual world. These two buildings were placed on the same street in order to balance each other out, with the office in the west and the temple in the east. The County Government Office was originally built in 1346, during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), and is the largest of its kind in China. It represented a vast complex containing the home of the local magistrate, various offices, a prison, a court, meeting rooms, and a scenic garden.