Xiwan

Over 300 years ago, during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), a simple dockworker named Chen Shifan made his fortune working at a port along the Yellow River. In order to celebrate this fine achievement, he decided to build himself a grand castle-like compound, which he carved into the side of a hill just one kilometre (0.6 mi) from the ancient town of Qikou. Generation after generation, his descendants constructed their own yaodongs or “loess cave houses” in the same area and eventually they formed the village of Xiwan. It may take a village to raise a child, but evidently it takes a family to raise a village! Sixteen generations of the Chen family have since called this humble village home and over 400 of its residents are descendants of Chen Shifan. Talk about keeping it in the family!

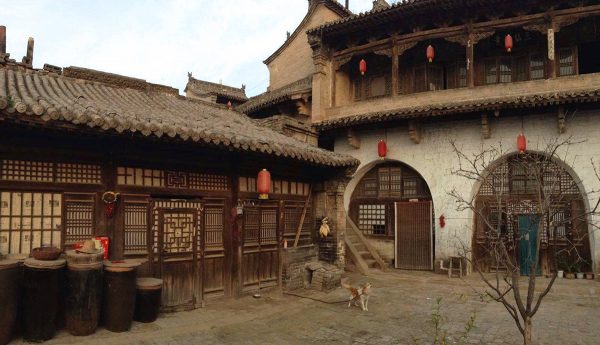

The village itself only occupies a narrow strip of the hillside, approximately 250 metres (820 ft.) in length and 120 metres (394 ft.) in width. The Chen’s Ancestral Hall is the centrepiece of the settlement, although the entire area is resplendent with beautifully constructed yaodongs. It functions less like a typical village and more like a large compound, with 30 small courtyards connected to each other by a row of five vertical lanes running from north to south. These secret lanes not only helped people communicate within the village, but also provided an escape route if it was under siege. They each represent the Five Elements of traditional Chinese philosophy: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water. However, they also signify the five branches of the Chen family and, historically, each branch would occupy their own personal lane.

The village boasts over 40 well-preserved yaodongs, complete with their ancient courtyards, which are widely regarded as some of the finest remaining structures from the Ming and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties. Each residence is stacked on top of the other as they creep their way up the hillside, with the roof of the house on the lower stage forming the courtyard of its neighbour on the upper stage. With stone walls and gate towers, they are markedly fortified structures designed to protect the village from intruders. That being said, nowadays the only people invading Xiwan are curious tourists!

Lijiashan

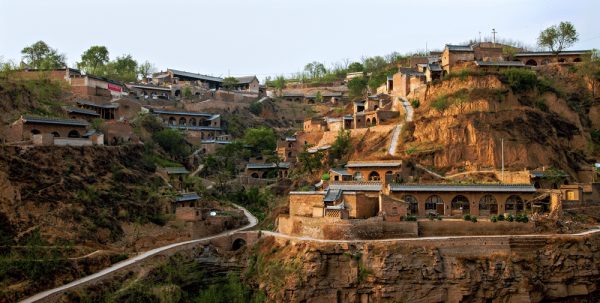

Clinging to the cliff-face of a deep valley within Lijia Mountain, the ancient village of Lijiashan blends seamlessly with its natural surroundings. At first glance, you may not even notice that it’s there! It rests about 10 kilometres (6 mi) from Qikou, a town whose history is inseparably intertwined with Lijiashan. Over 500 years ago, Qikou flourished as one of the major port towns along the Yellow River. It was a vital trading hub located at an impassable stretch of the river, where goods heading north or south would be unloaded at the port and carried overland by caravans. Families in the town made a fortune running hotels, caravan services, restaurants, shops, warehouses, and a myriad of other establishments catering to the regular influx of wealthy merchants. Some of them even became merchants themselves!

Many of these newly rich businessmen decided that, in the interests of safety, it would be best to move their families and their homes elsewhere. They squirreled their families away in the mountains, constructing secret villages where they could live in comfort. Lijiashan is one such village and its name, which means “Mountain Home of the Li Family”, is a reference to the fact that the two most luxurious mansions in the village were constructed by the Li family during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). In fact, the village is home to over 400 magnificent yaodongs or “loess cave houses”, which are buildings carved directly into the rocky outcrop of the mountainside. However, these aren’t just any old yaodongs!

These yaodongs are unique in that they were built by wealthy merchant families, rather than the other yaodongs in Shanxi province, which were typically the work of poor farmers. The yaodongs of Lijiashan are not humble earthen dwellings, but were constructed from the finest materials, including brick, stone, and tile. They are two or three storey affairs, complete with front courtyards resembling traditional Chinese courtyard houses. Resplendent with a plethora of stone carvings, brick sculptures, and woodcuttings, these yaodongs are more like mansions than simple caves.

In its heyday, Lijiashan was home to over 600 families, most of whom were from the Li clan. However, as the ancient port of Qikou gradually became obsolete so too did this venerable village. Dazzled by the opportunities on offer in China’s rapidly developing cities, many of its younger inhabitants have left in search of their own fortune. Nowadays, only 40 families remain and most of the residents are in their twilight years.

These locals depend upon tourism and allow visitors the unique chance to stay in their cave dwellings. In a stroke of luck, Lijiashan has risen to become a painter’s paradise. Every year, hundreds of artists flock to the village to take advantage of the stunning panoramic views. From the comfort of their rented cave rooms, they produce vivid images of the mountain valley and the picturesque yaodongs carved into its sides. After all, a picture paints a thousand words!

Zhenguo Temple

Located just 10 kilometres (6 mi) from the ancient city of Pingyao, Zhenguo Temple has a history that stretches back over 1,000 years. Its profound historical importance meant it was incorporated by UNESCO into the “Ancient City of Pingyao” World Heritage Site in 1997. Records suggest that the temple was originally established during the Northern Han Dynasty (951–979), since the “Wanfo” or “Ten-Thousand Buddha” Hall, its oldest surviving structure, was built in 963 AD. Constructed without the use of a single nail, this hall is a masterpiece of ancient architecture and is one of the three oldest wooden structures in China. So, if you ever need to knock on wood, this might be the best place to do it!

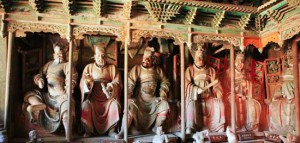

Within the hall itself, there are eleven sculptures that date all the way back to the Northern Han Dynasty. Outside of the Mogao Caves in Gansu province, they are the only examples of Buddhist sculpture in China dating back to this period. The main statue is that of Shakyamuni[1] Buddha, who is flanked by Bodhisattvas[2] and the Four Heavenly Kings of Buddhism. The Ten-Thousand Buddha Hall rests at the centre of the temple complex and is surrounded by a constellation of other halls, which were added periodically throughout the temple’s history.

At its southern end, the complex opens with Tianwang Hall, which acts as the temple’s gate and was originally built during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). The hall is flanked by two towers, and contains statues of Guan Yu, a renowned military general from the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280), alongside statues of the Four Heavenly Kings. Its northernmost point is marked by Sanfo Hall, which was constructed during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). The name “Sanfo” literally translates to mean “Three Buddhas” and is named for the statues of the three forms of Shakyamuni that rest within its walls. The delicate murals that bedeck its walls similarly depict the life of Shakyamuni in vivid colour.

While this trio represents the three main halls of the complex, there are two smaller halls called Guanyin Hall and Dizang Hall on the eastern and western edges of the northern courtyard, which both date back to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). These are dedicated to Guanyin, the bodhisattva of mercy, and Dizang, the bodhisattva charged with aiding the deceased. Spanning many of the major dynasties, a walk through Zhenguo Temple’s halls is like taking a trip through Chinese history!

Notes:

[1] Shakyamuni: One of the titles of Gautama Buddha, the central figure and founder of the Buddhist faith. It is derived from the place named Sakya, which is where he was born.

[2] Bodhisattva: The term literally means “one whose goal is awakening”. It refers to a person who seeks enlightenment and is thus on the path to becoming a Buddha. It can be applied to anyone, from a newly inducted Buddhist to a veteran or “celestial” bodhisattva who has achieved supernatural powers through their training.

The Wang Family Compound

The Wang Family Compound may not be the most popular of the Shanxi Grand Compounds, but it’s actually four times the size of the renowned Qiao Family Compound and even rivals the Forbidden City in its magnitude! Like many of the Shanxi Grand Compounds, it is located in Lingshi County, approximately 35 kilometres (22 mi) from the ancient city of Pingyao. Stretching over an area of 150,000 square metres (1614587 sq. ft.), its vast complex consists of six castle-like courtyards, six lanes, and one street. In-keeping with its legendary size, its five main courtyards were designed to symbolically represent the five lucky animals according to traditional Chinese culture: the Dragon, the Phoenix, the Tortoise, the Qilin (Chinese Unicorn), and the Tiger. In short, you could say the Wang family were living in the belly of the beast!

The Wang Family Compound may not be the most popular of the Shanxi Grand Compounds, but it’s actually four times the size of the renowned Qiao Family Compound and even rivals the Forbidden City in its magnitude! Like many of the Shanxi Grand Compounds, it is located in Lingshi County, approximately 35 kilometres (22 mi) from the ancient city of Pingyao. Stretching over an area of 150,000 square metres (1614587 sq. ft.), its vast complex consists of six castle-like courtyards, six lanes, and one street. In-keeping with its legendary size, its five main courtyards were designed to symbolically represent the five lucky animals according to traditional Chinese culture: the Dragon, the Phoenix, the Tortoise, the Qilin (Chinese Unicorn), and the Tiger. In short, you could say the Wang family were living in the belly of the beast!

Like many of the Jin merchant families from this region, the Wang family began as simple farmers and eventually graduated to becoming small time businessmen. During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), they expanded their business gradually and hoped that, ultimately, their efforts would grant their successors the opportunity to gain official positions in the government. By the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the family had reached the peak of their prosperity and over 100 members of the Wang family were high-ranking officials! Unfortunately all this good work would be undone towards the end of the dynasty, as future generations of the Wang family lacked their forebears’ ambition. After having lived in this grand mansion for 27 generations, the last members of the Wang family left in 1996 and it was opened to the public in 1997.

Nowadays, only two of the colossal courtyards and one of the ancestral halls are open to tourists, comprising a total of 123 smaller courtyards and over 1,100 rooms. The complex has been separated into three main areas: the Red Gate Castle; the Gao Jia Ya or East Courtyard; and the Chongning Bao. Built from 1739 to 1793, the Red Gate Castle covers a colossal 25,000 square metres (269,098 sq. ft.) and contains 29 courtyards. Its name is derived from its characteristic red gate, which is the only one in the compound, and its layout is designed to look like the Chinese character “王” (Wáng), which means “king”. It should come as no surprise that this character happens to be the Wang’s family name. Talk about making something in your image! It thus seems quite fitting that the Wang Museum, which details the history of the family, should be found in the Red Gate Castle.

The Gao Jia Ya, which was constructed between 1796 and 1811, may not be as expansive as the Red Gate Castle, but it boasts some of the finest woodcuttings, stone-carvings, and brick sculptures in the compound. It is a somewhat labyrinthine structure, consisting of multifarious courtyards and connecting alleyways. Nowadays it is also used to exhibit a lavish collection of items that once belonged to the Wang family. Similarly, the Chongning Bao is now used primarily to display elegant paintings and woodcuttings by the celebrated artist Li Qun. On August 18th of every year, a Tourism Festival is held in the Wang Family Compound, where visitors have the opportunity to watch and take part in traditional folk activities. It’s the ideal time to embrace the ancient culture in which this grand work of architecture was conceived.

Find more stories about Wang Family Compounds and Jin Merchants on our tour: Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages

The Qiao Family Compound

The Qiao Family Compound is widely thought to be the most famous and popular Shanxi Grand Compound in the province of Shanxi, largely thanks to its starring role in Zhang Yimou’s moving drama Raise the Red Lantern. These magnificent courtyard houses were originally built during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties by prosperous families hailing from Shanxi province. Located in the village of Qiaojiabao approximately 30 kilometres (19 mi) from the historic city of Pingyao, the Qiao Family Compound was originally known as Zai Zhong Tang (在中堂) and was constructed in 1756 by a renowned merchant named Qiao Guifa, who made his fortune selling tea and tofu.

However, the Qiao family wouldn’t reach its zenith until the third generation, when Qiao Zhiyong became the head of the family. Qiao Zhiyong was an astute businessman and, during his lifetime, he built up an unparalleled mercantile empire in the province of Shanxi. When he was head of the family, the Qiao clan controlled over 200 shops located throughout the country, including a number of prototype banks, pawnshops, teahouses, and granaries. Of the three great expansions that the Qiao Family Compound underwent, it was Qiao Zhiyong who was responsible for the largest and most extravagant. He was considered such an intriguing figure in Shanxi province that, in 2006, a television series was made about his life, known as Qiao’s Grand Courtyard. In short, he got more than just his fifteen minutes of fame!

Yet it wasn’t just Qiao Zhiyong’s business acumen that enabled the compound to flourish. During the Qing Dynasty, a military coalition known as the Eight-Nation Alliance was set up in response to the violent Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) in China. Included in this alliance were the Empire of Japan, the Russian Empire, the British Empire, the French Third Republic, the United States, the German Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1900, the alliance sent troops to liberate their embassy in Beijing, which had been under siege. Once they had resolved the issue with the embassy, they decided to invade and occupy the city of Beijing. Talk about taking liberties!

Yet it wasn’t just Qiao Zhiyong’s business acumen that enabled the compound to flourish. During the Qing Dynasty, a military coalition known as the Eight-Nation Alliance was set up in response to the violent Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) in China. Included in this alliance were the Empire of Japan, the Russian Empire, the British Empire, the French Third Republic, the United States, the German Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1900, the alliance sent troops to liberate their embassy in Beijing, which had been under siege. Once they had resolved the issue with the embassy, they decided to invade and occupy the city of Beijing. Talk about taking liberties!

In response, the governor-general of Shanxi province ordered that all foreigners in the region were to be killed on site. Seven Italian sisters, who were working in the country as missionaries, managed to escape the ensuing panic and eventually arrived at the Qiao Family Compound. They begged Qiao Zhiyong for protection and he allowed them to hide within the compound, which ended up saving their lives. In honour of his benevolence towards their people, the Italian embassy awarded him with an Italian flag, which he proudly displayed within the compound.

Many years later, during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), the Japanese army invaded Shanxi province and left destruction in their wake. However, the presence of this flag meant that Japanese troops chose to leave the Qiao Family Compound unharmed, since Italy was one of Japan’s political allies at the time. Having been spared a gruesome fate, the compound was occupied by the Qiao family right up until 1985, when it was converted into a museum.

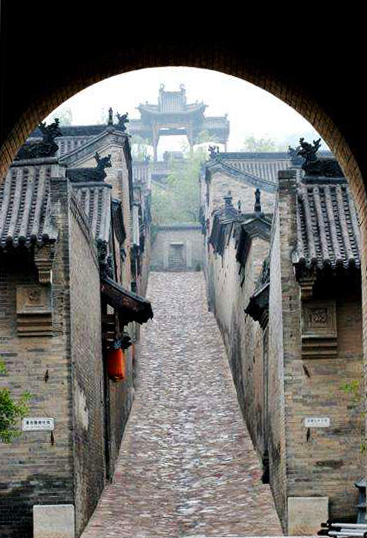

After numerous renovations in its 160-year-long history, it now stretches over a staggering 8,724 square metres (93,904 sq. ft.) and is comprised of 6 large courtyards, 20 smaller courtyards, one ancestral temple, and 313 rooms. Its layout is designed to resemble the Chinese character “囍”, which means “happiness” and is meant to symbolically express the Qiao family’s hope for a bright future. Some of its courtyards are flanked at their entrance by fearsome stone guardian lions, while others have their eaves delicately painted with tableaus of Chinese folk legends or their gates engraved with beautiful patterns.

After numerous renovations in its 160-year-long history, it now stretches over a staggering 8,724 square metres (93,904 sq. ft.) and is comprised of 6 large courtyards, 20 smaller courtyards, one ancestral temple, and 313 rooms. Its layout is designed to resemble the Chinese character “囍”, which means “happiness” and is meant to symbolically express the Qiao family’s hope for a bright future. Some of its courtyards are flanked at their entrance by fearsome stone guardian lions, while others have their eaves delicately painted with tableaus of Chinese folk legends or their gates engraved with beautiful patterns.

Each courtyard consists of a principle room, which was reserved for the host and is distinguished by its tiled roof. The side rooms, which were designated for the guests and servants, have brick roofs instead. These differences in style helped to break up the monotony of the architecture, whilst simultaneously indicating the hierarchy of the compound’s residents. A special corridor on each roof enabled guards to patrol the entire compound with ease. Not only that; the compound is entirely surrounded by 10-metre (33 ft.) high walls, which endow it with a fortress-like appearance from the outside. After all, a man’s home is his castle, and castles need round-the-clock protection!

Wandering through the compound’s many rooms and corridors is a banquet of delights, resplendent with some of the finest wood carvings, brick carvings, stone carvings, murals, and wall sculptures in northern China. Nowadays it houses over 2,000 cultural relics, including porcelain, silk embroidery, paintings, and divine furnishings that are sure to transport you back to the luxurious lifestyle of the Qiao family. These lavish decorations are sure to entice you, while the various exhibitions on the history of the Qiao family and the business customs of the Qing Dynasty will provide you with an invaluable insight into life in ancient China. Just don’t stay too long, or you may never want to leave!

Hukou Waterfall

Ranking just after the Huangguoshu Waterfall, the Hukou Waterfall is the second largest waterfall in China and the only yellow waterfall in the world. Yet there’s nothing yellow-bellied about this powerful natural phenomenon! It rests at a point along the Yellow River where the riverbed suddenly tapers down from 300 metres (984 ft.) to 50 metres (164 ft.), transforming tranquil waters into cascading rapids. The result is a magnificent 15 metre-high (49 ft.) and 20 metre-wide (66 ft.) waterfall that gushes down from the narrow opening like bubbling water pouring from a teapot. This is what earned the waterfall its unusual name, as “hukou” literally translates to mean “a spout” in Chinese. That being said, don’t go trying to pour yourself a cuppa from this fierce torrent!

The waterfall is located at the intersection between the provinces of Shanxi and Shaanxi, about 165 kilometres (103 mi) west of Fenxi City and 50 kilometres (31 mi) east of Yichuan County. The provinces are in fact connected by Qilangwo Bridge, which spans the stretch of river just beneath the waterfall. The waterfall itself can be found within Jinxia Grand Canyon and is flanked on both sides by Hukou Mountain. Its size and velocity changes depending on the season, and can easily reach a staggering 50 metres (164 ft.) in width during the rainy season. In winter, it’s said to be particularly beautiful as the water slows and the riverbed is lined by shimmering icicles.

According to the locals, the thundering sound of the water can be heard for miles around, and the current is so strong that boats have to be pulled out of the river long before they even get to the waterfall. These boats have to either be shipped by truck or carried around this section of the river before they can be put back in the water. So, while the Hukou Waterfall might float your boat metaphorically, the harsh reality is it’s far more likely to sink it in real life!

According to the locals, the thundering sound of the water can be heard for miles around, and the current is so strong that boats have to be pulled out of the river long before they even get to the waterfall. These boats have to either be shipped by truck or carried around this section of the river before they can be put back in the water. So, while the Hukou Waterfall might float your boat metaphorically, the harsh reality is it’s far more likely to sink it in real life!

Just below the waterfall, be sure to look out for a shining stone that the locals call the guishi or “ghost stone”. Rumour has it that this mysterious stone moves up and down depending on the water level and, no matter how high the water is, it’s always partly visible. It might not be the stuff of horror films, but it’s certainly pretty unique!

The Yingxian Wooden Tower

The Yingxian Wooden Tower, also known as the Shakyamuni[1] Pagoda of Fogong Temple, rests just 85 kilometres (53 mi) south of Datong City in western Yingxian County. Having been built without a single nail or rivet, it is a masterpiece of carpentry and the oldest surviving wooden pagoda in the world. It has reached such a level of fame in China that it is now widely referred to simply as “Muta” (木塔) or “Wooden Tower”. At the grand old age of 959, this tower has pushed its woody competitors to the side and taught them to respect their elders!

The tower was originally built in 1056 by Emperor Daozong of the Liao Dynasty (907–1125), which controlled an empire encompassing Mongolia, northern Korea, and northern China, and was established by a nomadic subgroup of Mongolian people know as the Khitans. Emperor Daozong was a devout Buddhist and his father, the preceding Emperor Xingzong, was a native of Yingxian County. This would perhaps explain the isolated location of the tower, as pagodas such as these were normally erected to symbolise the death of Buddha and its placement may have been Emperor Daozong’s way of equating the importance of Buddha’s death with that of his father.

The tower was placed at the centre of Fogong Temple, which was known as Baogong Temple until its name was changed during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). According to local historical documents, from the years 1056 to 1103 it withstood a total of seven earthquakes and, right up until the 20th century, it required only ten minor repairs. Talk about resilient! Unfortunately, it sustained major damage during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) but, when it underwent the necessary repairs in 1974, renovators uncovered over 50 block-printed and handwritten scrolls of Buddhist sutras[2] dating back to the Liao Dynasty. These scrolls helped historians to finally establish that the use of moveable type printing had indeed spread widely across China after being developed by the Song Dynasty (960-1279). So it seems every cloud really does have a silver lining!

Although the archway, bell tower, drum tower, and shrine to Shakyamuni Buddha were all rebuilt during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the wooden tower itself is in its original condition and has been stunningly well-preserved. It stands on a 4 metre (13 ft.) high stone platform that is delicately decorated with crawling lion sculptures in the Liao Dynasty style, and it towers in at a height of over 67 metres (220 ft.). Looking at it from the outside, it appears to have only five storeys, but walk inside and you’ll soon realise that there are in fact nine storeys in total. Just when you thought you were going to have a relaxing climb to the top!

Although the archway, bell tower, drum tower, and shrine to Shakyamuni Buddha were all rebuilt during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the wooden tower itself is in its original condition and has been stunningly well-preserved. It stands on a 4 metre (13 ft.) high stone platform that is delicately decorated with crawling lion sculptures in the Liao Dynasty style, and it towers in at a height of over 67 metres (220 ft.). Looking at it from the outside, it appears to have only five storeys, but walk inside and you’ll soon realise that there are in fact nine storeys in total. Just when you thought you were going to have a relaxing climb to the top!

An 11-metre-high (36 ft.) statue of Shakyamuni Buddha takes pole position at the centre of the first floor, with an ornate caisson[3] directly above its head. Similar caissons bedeck the ceilings of every storey in the pagoda and its walls are beautifully decorated with vibrant murals and vivid sculptures that all reflect the Liao Dynasty style. There are windows on all eight sides of its top floor that provide stunning views of the surrounding countryside and supposedly, on a clear day, the tower itself can be seen from up to 30 kilometres (19 mi) away!

[1] Shakyamuni: One of the titles of Gautama Buddha, the central figure and founder of the Buddhist faith. It is derived from the place named Sakya, which is where he was born.

[2] Sutra: One of the sermons of the historical Buddha

[3] Caisson: Also known as a caisson ceiling or zaojing, it is a feature of East Asian architecture commonly seen on the ceilings of temples or palaces, usually at the centre or directly above an object of importance, such as a throne or statue. Generally speaking, it is a sunken square, octagonal, hexagonal, or circular panel set into a flat ceiling that has been richly carved and decorated.

Mount Heng

Located just 62 kilometres (39 mi) south of Datong City, Mount Heng is a behemoth of a mountain range and consists of over 100 separate peaks. Not only is it considered one of China’s Five Great Mountains, but it also boasts the highest peak of them all, Tianfeng Peak, which towers in at over 2,100 metres (6,900 ft.) in altitude. To put that into perspective, it’s nearly twice the size of Ben Nevis, the tallest mountain in the UK! Yet it’s not the mountain’s size that has earned it such prestige, but its religious value. According to the Chinese religion of Taoism, Mount Heng is considered a sacred mountain and has been a site of pilgrimage since the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1045-256 BC).

Located just 62 kilometres (39 mi) south of Datong City, Mount Heng is a behemoth of a mountain range and consists of over 100 separate peaks. Not only is it considered one of China’s Five Great Mountains, but it also boasts the highest peak of them all, Tianfeng Peak, which towers in at over 2,100 metres (6,900 ft.) in altitude. To put that into perspective, it’s nearly twice the size of Ben Nevis, the tallest mountain in the UK! Yet it’s not the mountain’s size that has earned it such prestige, but its religious value. According to the Chinese religion of Taoism, Mount Heng is considered a sacred mountain and has been a site of pilgrimage since the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1045-256 BC).

It is sometimes referred to as Northern Hengshan because there is another Mount Heng in Hunan province which is coincidentally also one of the Five Great Mountains. Although their names are written differently in Chinese, they are pronounced in the same way and so the prefixes “northern” and “southern” are used to differentiate them. Imagine having twins named “Stephen” and “Steven”, and you get the idea!

According to legend, over 4,000 years ago Emperor Shun (c. 2294-2184 BC) was on a tour of his northern territory when he came upon Mount Hengshan and was so impressed by it that he simply named it Beiyue (北岳) or “Northern Mountain”. When it came to imperial prestige, Mount Hengshan had literally reached the pinnacle! Another legend purports that Zhang Guolao, one of the Eight Immortals in Taoist mythology, secluded himself on the mountain and is still there somewhere practising his faith. So if you bump into any strange old men while you’re hiking, be sure to be polite!

The mountain was held in such high esteem that a temple known as the Shrine of the Northern Peak or Beiyue Temple was erected there during the Han Dynasty (206 BC– 220 AD) and was dedicated to the god within the mountain. During the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), Emperor Qin Shi Huang not only named it as one of the 12 most sacred mountains, but also regarded it as the “Second Greatest Mountain in the entire World”. From then onwards, emperors, scholars, travellers, poets, monks, and people from all walks of life came to visit this alluring mountain range. Many of them left behind stone inscriptions extolling its incredible beauty, which can still be seen along the mountain paths today.

However, its northerly location meant that it was frequently cut off from China proper, as historically northern China was often under the control of non-Chinese kingdoms. This meant that it was not as accessible to pilgrims as the other Five Great Mountains, and so as a consequence it is the least-developed and least-visited of the five. Although therefore it is considered to have less religious importance, it is also less crowded and less commercialised, making it a more peaceful and isolated place to go hiking. In the summer, its hills come to life in a flurry of lilac blossoms, and its verdant pines, elms, firs, poplars, and bountiful forests provide stunning views throughout the year.

Alongside the Beiyue Temple, perhaps its greatest claim to fame is the Hanging Temple, which has survived for more than 1,500 years clutching precariously to the side of a cliff. The temple’s unusual appearance, coupled with the fact that it is dedicated to not just one religion but to Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism, means it has recently become a mecca for visitors looking to explore China’s architectural curiosities.

Yet this isn’t the only bizarre feature the mountain has to offer. The Kutian or “Sweet and Bitter” Wells are located about halfway up its slope and are simply two wells placed very close together. For reasons unknown, the water from one well is sweet and refreshing, while the water from its neighbour is bitter and has a distinctly unpleasant aftertaste. Perhaps one well is the other’s evil twin! In spite of the fact that the “sweet” well is only a few feet deep, its waters are inexhaustible, further adding to the mystery of this exceptional oddity. In fact, during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), Emperor Xuanzong visited the “sweet” well and found it so fascinating that he christened it “Dragon Spring”.

The area surrounding Mount Heng is distinctly less magical, as it was once a battleground and its plains have been ravaged by centuries of warfare. Relics of these ancient skirmishes can be found littered throughout the landscape, from tactical passes and small fortresses to colossal castles and beacon towers. The most well-known of these is Golden Dragon Gorge, which is a deep yet narrow pass that was used by General Yang Ye of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) to resist an invasion from the neighbouring Liao Dynasty (916-1125).

Other natural sites on the range include Sisters-in-Law Cave, Flying Stone Cave, Tiger Wind Gap, and Clouds Out Cave, which are all symbolically named and as such are imbued with a certain mystical quality. Clouds Out Cave is arguably the most spectacular as, on a clear and sunny day, it looks like any other cave, but when it’s raining or foggy then mist will billow out of the cave’s entrance and endow it with an ethereal appearance. Perhaps it’s haunted by the soldiers who died in Golden Dragon Gorge; perhaps it’s where Zhang Guolao lives; or perhaps there’s just a hole somewhere in the top of the cave!

The Mount Heng is one of the many wonderful stops on our Explore the Ancient Tradition of Tai Chi tour

Shuanglin Temple

Just 6 kilometres (4 mi) southwest of Pingyao Ancient Town, nestled deep within the countryside of Shanxi, the small village of Qiaotou hosts one of the most magnificent Buddhist temples in China. The Shuanglin Temple, which is included under Pingyao as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is noted not only for its venerable age but for the more than 2,000 painted statues that decorate its halls.

This vast collection, made by moulding clay over wooden frames, has earned the temple the nickname “The Museum of Coloured Sculptures”. They are not purely works of religious art, but instead are imbued with human features and attributes to symbolise the unification of the spiritual and the physical, or rather the connection between deities and human beings.

Unfortunately the lack of historical documents has meant that researchers currently do not know exactly when the temple was first built. However, the oldest stone tablet within the complex indicates that it was rebuilt in 571 AD during the Northern Qi Dynasty (550-577) and two huge locust trees, planted during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), attest to this ancient origin. It’s estimated that the temple itself is over 1,400 years old, although it underwent large scale restoration throughout the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties and much of its surviving architecture reflects those styles. Bear in mind, when you’re 1,400 years old, you need a little extra help to keep looking good!

It was originally called Zhongdu Temple but was renamed Shuanglin during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The term “shuang” means “two” or “double” while “lin” means “woods”, and together the name refers to one of Sakyamuni’s[1] sutras[2] in which he states that “nirvana is between two trees”. Unfortunately he never specified which two trees they were!

It was originally called Zhongdu Temple but was renamed Shuanglin during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The term “shuang” means “two” or “double” while “lin” means “woods”, and together the name refers to one of Sakyamuni’s[1] sutras[2] in which he states that “nirvana is between two trees”. Unfortunately he never specified which two trees they were!

The many sculptures littered throughout the temple were carved between the 12th and 19th centuries. Their height varies from 30 centimetres (1 ft.) right up to nearly 4 metres (13 ft.) and the vast majority are of Buddha or various bodhisattvas[3], but a few are warrior guards, heavenly generals, and even common people. Their colourful backdrops are resplendent with mountains, rivers, clouds, flowers, and dense forests.

The complex is surrounded by a high wall with a gate, giving it the appearance of a fortress. Buddhism may be a peaceful religion, but it still has to protect itself! The inner temple consists of three main sections: the ten main halls in the centre; the sutra library and monks’ living quarters in the east; and a courtyard to the west.

In the Hall of the Heavenly Kings, a sculpture of the deity Maitreya sits at the centre, while the Four Heavenly Kings rest in the north. They are all 3 metres (10 ft.) in height and each one carries an implement of symbolic importance. The first has a pipa[4], which symbolises earth; the second has a sword, which represents gold; the third has a snake, which signifies wind; and the final one holds an umbrella, which unsurprisingly denotes water. Together these instruments are meant to bless the worshipper with good weather, abundant crops, and subsequent wealth. After all, who would pray for a bunch of snakes and umbrellas?

The Arhat Hall is home to a large sculpture of Guanyin, the Buddhist deity of mercy, flanked by eighteen sculptures of arhats[5]. The face and aspect of each arhat is different; one is drunk, one is sick, some are fat, and some are thin. They are all designed to show off the artisans’ particular skill at carving and among them the mute arhat is considered the most magnificent.

His facial expression is heavily exaggerated, with pursed lips, a deeply furrowed brow, and piercing eyes, and his chest and belly are distended, as if to suggest he is struggling to breathe. His expression, coupled with his posture, implies that he has seen much injustice in the world but, as a mute, can only communicate his frustration through his body language.

In the Thousand-Buddha Hall, there is another statue of Guanyin with her right leg bent and her left leg placed delicately on a lotus leaf. A wonderful sculpture of Skanda, the celestial guardian devoted to protecting Buddhist monasteries, is at her side. The 500 statues and paintings within this hall are often studied to help recreate traditional outfits of the Ming Dynasty.

Yet another statue of Guanyin takes centre-stage in the Bodhisattva Hall, but this time in the style of the Thousand-Armed Guanyin. Remember she’s the deity of mercy, not modesty! The statue does not literally have a thousand arms, but the many clawed hands that surround this figure are both strangely attractive and intimidating. It’s bad enough being tickled by just two hands, but imagine how it would feel with twenty!

[1] Sakyamuni: One of the titles of Gautama Buddha, the central figure and founder of the Buddhist faith. It is derived from the place named Sakya, which is where he was born.

[2] Sutra: One of the sermons of the historical Buddha.

[3] Bodhisattva: The term literally means “one whose goal is awakening”. It refers to a person who seeks enlightenment and is thus on the path to becoming a Buddha. It can be applied to anyone, from a newly inducted Buddhist to a veteran or “celestial” bodhisattva who has achieved supernatural powers through their training.

[4] Pipa: A four-stringed plucking instrument that has a pear-shaped wooden body and anywhere from 12 to 26 frets. It is sometimes referred to as the Chinese lute.

[5] Arhat: A “perfected person” who has achieved enlightenment by following the teachings of Buddha.

Join our travel to visit the Shuanglin Temple in Shanxi: Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages