The term the ‘Silk Road’ was coined by a German geographer named Ferdinand von Richthofen in the 19th century. It refers to the commercial routes that connected mainland China with central Asia during ancient times. Afterwards various scholars expanded the term so that it now also applies to the routes that connected China to west Asia and even to Africa and Europe. The most common commodity exported from China was silk. However, the Silk Road was not solely used for commercial trade, but was also a point of cultural exchange between various ethnic groups in China, central Asia, west Asia, and Europe.

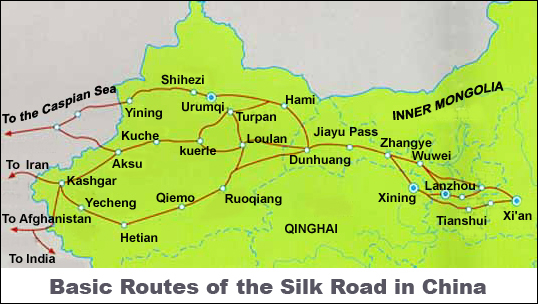

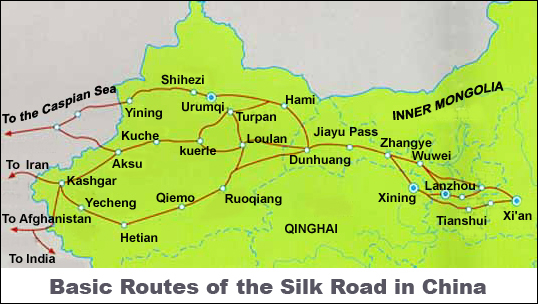

The Silk Road is in fact not only one road, but consists of several roads, so many scholars prefer to call it ‘the Silk Routes’ instead.

Generally speaking, the Silk Road can be divided into three parts – the Eastern part, the Central part, and the Western part. The Eastern and Central parts are predominantly in China, while the Western part stretches across central and west Asia and even parts of North Africa and Europe.

Routes belongs to the Silk Road in China:

The Eastern Part of the Silk Road:

The Eastern part stretches from Xi’an or Luoyang, then goes northwest through Shaanxi province and Gansu province up to Dunhuang.

Xi’an was the capital of the Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C. – 9 A.D.), while Luoyang was the capital of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25 – 220). Nowadays Xi’an is the capital of Shaanxi province, and Luoyang is just a city in Henan province.

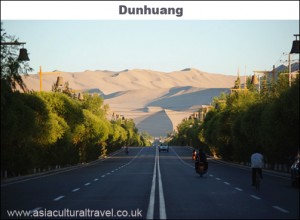

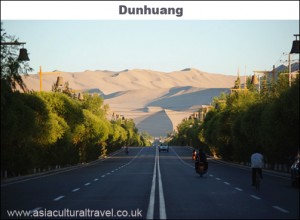

Dunhuang is in Gansu Province. It is one of the most famous attractions in China because of its fantastic Grottoes.

The road in the Eastern part was split into three routes when it reached Gansu province – the Northern Way, the Southern Way and the Central Way.

The Northern Way: This went from Jingchuan (in Gansu Province), through Guyuan (in Ningxia Province) and Jingyuan (in Gansu Province), and ended in Wuwei (in Gansu Province). It was the shortest of the three routes, but it needed to be short as it ran through the Gobi desert, which had few water sources.

The Southern Way: This went from Fengxiang (in Shaanxi Province), through Tianshui (in Gansu Province), Longxi (in Gansu Province), Linxia (in Gansu Province), Ledu (in Qinghai Province), Xining (in Qinghai Province), and finally ended in Zhangye (in Gansu Province). This road was famously known as ‘the Hexi Corridor’. It followed the Yellow River. It was easier to traverse than the other three routes but it was also much longer.

The Central Way: This went from Jingchuan (in Gansu Province), through Pingliang (in Gansu Province), Huining (in Gansu Province), Lanzhou (in Gansu Province), and ended in Wuwei (in Gansu Province). This route was the most popular because it was not too long and not too difficult to follow.

The Central Part of the Silk Road:

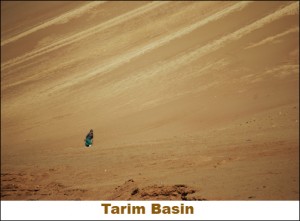

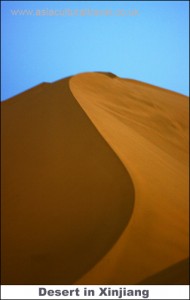

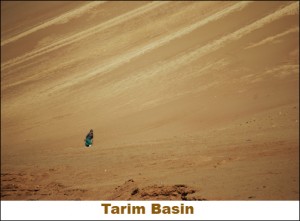

The road in the Central part was also separated into three routes. The routes in this part went from Dunhuang or Anxi (named Guazhou in ancient times) in Gansu Province, but from then on mostly went through Xinjiang province, particularly through the Tarim basin. All of the routes were frequently changed according to the appearance and disappearance of oases, which were the only water source along the desert tracts.

The Northern Way: This went from Anxi, through Kumul (in Xinjiang Province), Jimsar (named Tingzhou in ancient times, now in Xinjiang Province), Ili (in Xinjiang Province), and ended in Suyab (in Kyrgyzstan).

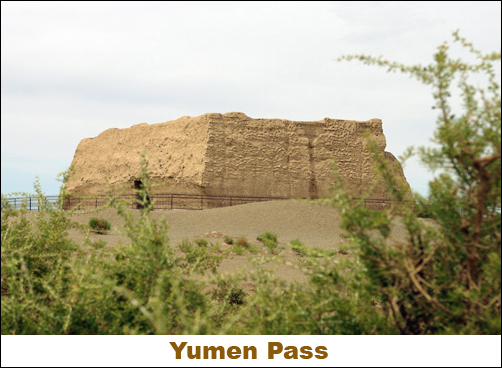

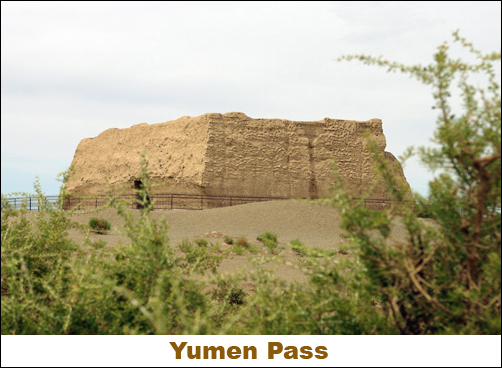

The Southern Way: This went from Dunhuang (or the Yumen Pass, or the Yang Pass), followed the southern edge of the Taklimakan desert, then went through Shanshan (in Xinjiang Province), Hotan (named Khotan in the ancient times, now in Xinjiang Province), Yarkant (in Xinjiang Province), and ended in the Pamir Mountains.

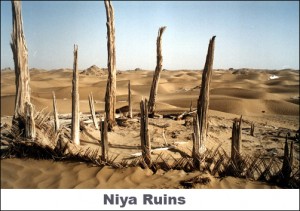

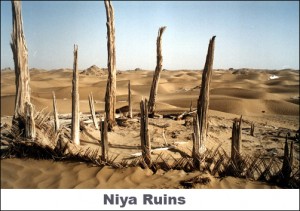

There were several important towns on this route, such as Qaran and Niya (the capital of the Jingjue Kingdom in ancient times). All of these towns have since disappeared because of the changing desert.

The Central Way: This went from the Yumen Pass (in Gansu Province), followed the northern edge of the Taklimakan desert, then went through Lop Nur (where the Loulan Kingdom was situated in ancient times), Turpan (once part of the Cheshi Kingdom and the Gaocheng Kingdom, now in Xinjiang Province), YanQi (in Xinjiang Province), Kuqa (capital of the Kuqa Kingdom in ancient times, now in Xinjiang province), Aksu (part of the Gumo Kingdom in ancient times, now in Xinjiang Province), Kashgar (in Xinjiang Province), and ended in the Fergana Valley (once part of the Dayuan Kingdom, now in Uzbekistan).

There were several important ancient Kingdoms and large towns on this route. However, nowadays most of these towns are just ruins in the desert or have disappeared entirely.

The History of the Silk Road

In ancient China, during the Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C. – 9 A.D.), the northern frontier of the Han people was often subjected to assault by the nomadic Xiongnu tribe. Xiongnu men were notoriously good at fighting. Since this nomadic group was causing so much damage, the Han Empire decided to proffer peace by sending them treasures and arranging marriages between Xiongnu people and members of the Han royal family. The Han Empire sent their princesses to wed Khans’ (leaders) of the Xiongnu people. In fact, these women were not real princesses but were actually just girls that served the Han emperors in the palace.

In 140 B.C. Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty ascended the throne. The power of the Han Empire had grown significantly by that time. Thus Emperor Wu was able to pursue a proactive foreign policy and set a goal to defeat the Xiongnu people.

Having learned that the Xiongnu people had killed the leader of the Dayuezhi Kingdom (located in the Western Regions1) and forced its citizens to leave their land, Emperor Wu planned to form an alliance with the citizens of Dayuezhi and attack the Xiongnu.

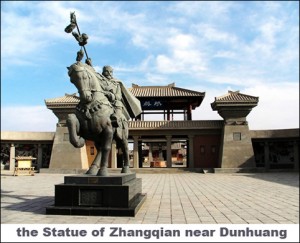

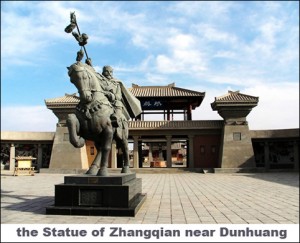

In order to implement this plan, in 138 B.C. Emperor Wu dispatched an envoy named Zhang Qian to the Western Regions. Leading more than a hundred men, Zhang Qian set off from Longxi (present-day Lintao in Gansu province). Unfortunately, on their journey they were captured by the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu forced Zhang Qian into exile in the grassland, where he stayed for more than a decade. Zhang Qian finally found an opportunity to escape and he continued his journey to the West. When he eventually arrived at Dayuezhi, he learned that its citizens had settled down in the Amu River basin and enjoyed their peaceful life there. They did not want to start a war with the Xiongnu.

Having failed to lobby an alliance between the citizens of Dayuezhi and the Han Empire, Zhang Qian embarked on his return journey. He was once again unexpectedly detained by the Xiongnu. However, this time he escaped after just one year.

In 126 B.C. Zhang Qian returned to Chang’an (present-day Xi’an in Shaanxi province), thirteen years after he had left.

Zhang Qian reported to Emperor Wu about what he had seen and heard in the Western Regions.

Emperor Wu was enthralled by Zhang Qian’s descriptions of foreign lands, exotic and tantalizing delicacies, precious stones of the brightest hue, local craftworks of the finest quality and many other things that Han people such as Emperor Wu had never heard of or seen before. Emperor Wu was so overwhelmed by these stories that he became fascinated with the Western Regions and their potential resources. So he decided to establish friendly ties with the people there.

In 119 B.C. Zhang Qian was dispatched to the Western Regions once again. He led a contingent of more than three hundred men and together they transported large quantities of gold, silk, cattle and sheep. Zhang Qian was incredibly lucky to have avoided the Xiongnu on this occasion. First they arrived in Wusu, which used to be to the southeast of Lake Balkhash. Wusu was an important hub in the Western Regions. Zhang Qian then sent his deputies to countries such as Dayuan, Kangju (present-day southeast Kazakhstan), Daxia (some scholars believed this became part of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom), the Parthian Empire (present-day northeast Iran), and Sindhu (ancient India), where they were welcomed and where they conducted large-scale exchanges. In 115 B.C. Zhang Qian returned to Chang’an. Dayuan, the Parthian Empire and some other regimes in the Western Regions all sent envoys to travel with him.

Zhang Qian opened the transportation routes between the east and west parts of the Asian mainland. From 104 B.C to 101 B.C., the Han Empire set up four counties (‘jun’ in Chinese) in the Western Regions: Jiuquan, Zhangye, Wuwei and Dunhuang (all in modern-day Gansu Province). They formally incorporated these counties into the Han Empire and thus made them Han territory. Thereafter, Han envoys and merchants constantly travelled to the Western Regions to carry out political and commercial activities, while caravans from the Western Regions travelled to central China for the same reasons. Large quantities of Chinese silk were shipped to Central Asia, West Asia and even Europe via these routes.

The Western Regions: In ancient times, Han people used this term to refer to places outside of the Yumen Pass in the west. Historically there were 36 Kingdoms recorded to have belonged to the Western Regions and they were all located in modern-day Xinjiang Province and Central Asia.

The Turmoil Surrounding the Silk Road

In 8 A.D. the Han Dynasty was faced with crisis. An official named Wang Mang tried to steal the throne and managed to succeed. He established the short-lived Xin Dynasty, in which he was the first and only emperor. 17 years after his ascension to the throne, the royal Han family waged war against Wang Mang and managed to reclaim the throne. To differentiate between these two Han Empires (the one before and the one after the Xin Dynasty), we call the first one the Western Han Dynasty and the second one the Eastern Han Dynasty (25 – 220 A.D.). They are so-called because the capital of the Western Han Dynasty was Chang’an, which is to the west, while the capital of the Eastern Han Dynasty was Luoyang, which is to the east.

The Silk Road had been busy since it was built during the Western Han Dynasty. However, because of the chaos caused by the civil war, the imperial court had paid less attention to governing the Western Regions. The Xiongnu seized this opportunity to fight back against the Han Empire and thus traffic on the Silk Road was interrupted.

From 58 to 75 A.D., the Han Empire recovered from the civil war and managed to re-establish its national influence. In 72 A.D., Emperor Ming of the Eastern Han Dynasty ordered his General, Dou Gu, to travel to the Western Regions and broker an alliance that would help them defend against the Xiongnu. At the same time, the Xiongnu also made efforts to absorb these small countries into their empire. However, after several armed conflicts, the Han Empire finally succeeded.

In 97 A.D., a Han envoy named Gan Ying set off from Kuqa to visit the Seleucid Empire (present-day Iraq), the Parthian Empire and a few other countries. In 166 A.D., the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus sent an envoy to the Eastern Han Empire and thus opened up friendly exchanges between China and some of the European countries.

During the Three Kingdom Period (220-280 A.D.), the Silk Road was extended west from the Pamir Mountains onwards. A new route was opened up along the northern foot of Mt. Tianshan. This new route was the rough beginnings of the Northern Way in the Central part of the Silk Road.

Due to the frequent wars and long-term political division during what is known as the Wei Jin and the Southern and Northern Dynasty period (220-589 A.D.), the imperial court’s ability to manage the Western Regions and operate along the Silk Road was adversely affected. However, the Silk Road was not interrupted and some routes even prospered during these tumultuous times. Not to mention that the dissemination of Buddhism to the east attracted a large number of monks from India and Central Asia to China, who brought with them their spiritual knowledge and rich Buddhist culture.

The Sui and the Tang Dynasties (581-907 A.D.) finally entered into a period of socio-economic and cultural development and prosperity after this long period of social and political discord. Their national influence was unprecedentedly powerful at this time. The imperial court established stronger contacts and exchanges with the Western Regions, and thus maintained the smooth flow of traffic on the Silk Road. In 630 A.D., the Tang army defeated the Eastern Turkic regime, which had previously occupied part of the Silk Road, and strengthened the imperial court’s friendly ties with the Western Turkic regime. Later on the Tang army once again claimed total authority over the Western Regions (modern-day Xinjiang) and, in 640 A.D., the imperial court of the Tang Dynasty set up a military administration there.

The powerful Tang Empire also unified the Mobei region (places in modern-day Inner Mongolia and Mongolia). This meant a channel of communication was opened up between the Western Regions and the northern frontier. At the same time, in addition to the main routes, many new sub-routes of the Silk Road were also opened up.

The Silk Road flourished during the early years of the Tang Dynasty and formally entered its golden period. Yet midway through the Tang Dynasty, with the increase of established sea routes, more and more western merchants were coming to China by boat. The Silk Road gradually began to decline. In 755 A.D. a local military official named An Lushan launched an armed rebellion against the Tang Dynasty. Most of the Tang army stationed in the Western Regions was called back to Chang’an to safeguard the emperor. The Tibetan Empire, seizing their chance while the northwest frontier was unguarded, occupied the Helong area (west of modern-day Gansu Province), and the Uighurs, in a similar bid, took control of the Altay Prefecture (west of modern-day Xinjiang). This caused the Tang Empire to lose control of the Western Regions and the Silk Road was interrupted once again.

During the Northern Song Dynasty (960 – 1127), the Han regime was weak and controlled a limited area. Its capacity to trade with the Western Regions and foreign countries was also impeded. The Silk Road was, in a sense, practically closed. By the time the Southern Song Dynasty (1127 – 1279) began, as a result of vigorous support from the imperial court coupled with advances in shipbuilding technology, sea routes became the major channel for China’s external communication and trade. This meant that the Silk Road was almost completely abandoned.

In the 13th century, the Mongolian Empire rose to power in the northern grasslands. Having conquered the kingdoms of West Xia, Jin, and the Southern Song Dynasty, they unified China and established the Yuan Empire (1271 – 1368). The Yuan imperial court set up a pothouse system (a system of pubs or inns that were set up along the road by the imperial court) which enabled the Silk Road to flourish once again.

In 1391, the Emperor Taizu of the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644) sent an army to capture Kumul. In 1406, the Emperor Chengzu of the Ming Dynasty established an administrative office in Kumul as a base for implementing his economic policies in the Western Regions. But the Ming Empire didn’t hold power in the Western Regions for long. In 1472, a Mongolian leader named Chagatai Khan led his army to attack and eventually capture Kumul. The Ming army was forced to retreat to the Jiayuguan Pass (in Gansu Province), leaving the regions beyond the Jiayuguan Pass in political and social chaos. Although local trade among the civilian population still travelled along the Silk Road, the prosperity that the Silk Road had enjoyed no longer existed.

In the 15th century, due to the Ottoman Empire’s occupation of Constantinople (the capital city of the Eastern Roman Empire), the established trade routes between Europe and China became much more treacherous. More and more Europeans attempted to travel to the Far East by sea instead. In 1498, D. Gama discovered the Indian Ocean trade route, and thus a new channel for trade was opened between the East and the West. Meanwhile the Silk Road was gradually fading away and becoming a relic of its former glory.

Cultural and Technological Exchange on the Silk Road

The prosperity of the Silk Road facilitated the dissemination of advanced technologies and cultural features of ancient China to countries in the Western Regions, and even went as far as Central Asia, Europe and Africa. It also introduced China to technology, art and culture from various western countries.

Westward Dissemination of Chinese Culture and Technology:

Sericulture and Silk Weaving Technology

Among the commodities exported to the West via the Silk Road, silk was naturally the most famous.

In the book The Buddhist Records of the Western World by Xuanzang1, there is a historical record of how sericulture spread to the West. It states that around about 420 to 440 A.D., when the Silk Road was re-opened, the king of the Qusadanna Kingdom (located in present-day Khotan in Xinjiang) was so impressed by the elegance and beauty of the silk from ancient China that he sent his envoy to China to buy silkworm eggs and mulberry seeds. His request was not only immediately refused, but also alerted the imperial court, which had recently intensified its interrogation and examination of people who crossed the border in order to prevent the export of mulberry seeds and silkworm eggs. Later on, the king of Qusadanna proposed to one of the Han princesses, and hinted that she should smuggle silkworm eggs and mulberry seeds to him after they were wed. The princess secretly hid some silkworm eggs in her hair and also brought with her some women who were particularly skilled in the art of sericulture and silk weaving. They then built a city, named “Deer-shooting” in English, where they taught local women to grow mulberry trees and raise silkworms. Not long thereafter, the country was full of mulberry trees. Sericulture and silk reeling was quickly popularized and mastered by many of the locals. According to archaeological findings, remains of ancient mulberry trees have been unearthed both in the sand sea of Lop Nur and the ruins of the ancient Shanshan Kingdom. It was confirmed that these ancient mulberry trees were planted before the 4th century, which just about coincides with the time that the mulberry seeds and silkworm eggs were allegedly smuggled into the West.

According to the Roman historian Procopius, Chinese sericulture was introduced to the Eastern Roman Empire around 550 A.D.

During the 7th century, West Asia was occupied by the Arab Empire. In 751, a battle broke out between the Arab army and the Tang army in the Talas River area of present-day Kazakhstan. The Tang army was defeated and some silk weavers and paper workers among the Tang soldiers were captured. It is possible that this was how the Chinese arts of silk weaving and papermaking made their way to West Asia.

Tea

As a specialty of central China, tea was only produced in the areas surrounding the Yangzi River and the Huai River, and some areas in the south of China. Tea found its way into the Western Regions some time during the Tang Dynasty. In the 8th year of the Wude Period of Emperor Gaozu’s reign (625 A.D.), ethnic minorities from the Northwest, such as the Turkic people and the Tuyuhun people, attempted to promote mutual trade with the Han ethnic group. The Tang Dynasty approved of their request to trade and offered up products made from the finest silk and quality tea as their major commodities when trading with these minorities.

During the rise of the Mongolian Empire in the 13th century, tea was a luxury item available only to Mongolian aristocrats. It was not until the 14th century that tea became a popular drink for ordinary Mongolian citizens and subsequently spread to areas beyond the Western Regions. During the Ming Dynasty, the imperial court established a government-run Tea-Horse Trading System and set up Tea-Horse Agencies in Gansu and Sichuan whose job it was to govern the tea trade. The imperial court aimed to exert control over ethnic minorities in the Western Regions by regulating the Tea-Horse Trade. Tea-drinking culture had already become a staple part of the daily life of ethnic minorities in the Western Regions. Its influence had even spread to Central Asia.

Note: There is a “second Silk Road” in the south of China, which is named the Ancient Tea-Horse Road. This road was established more than a thousand years ago for trade between Yunnan, Sichuan and Tibet. The major commodities traded on this route were tea and horses.

Apart from silk and tea, many scholars believe that the technology behind papermaking, paper printing and gunpowder production also disseminated from China to the western world via the Silk Road.

Eastward Dissemination of Foreign Culture and Technology:

Buddhism

Buddhism entered the Western Regions around 60 A.D. from Gandhāra. Knowledge of the religion then spread through the Yumen Pass and the Hexi Corridor and penetrated into inland parts of China. Gradually it spread throughout the whole country.

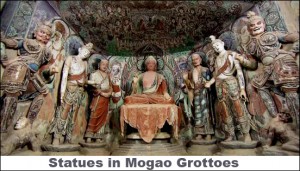

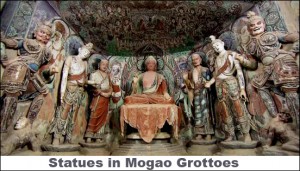

Thanks to the eastward dissemination of Buddhism, various styles and works of art, such as grottoes, sculptures, and mural paintings, also made their way into China. These styles were then integrated with more traditional Chinese art-styles and a large volume of Buddhist sculptures and mural paintings were produced in China. The most famous of these are the Grottoes at Dunhuang, Maijishan, Yungang and Longmen. There are also many less famous Grottoes in Xinjiang province.

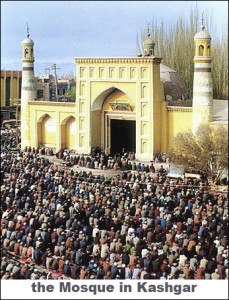

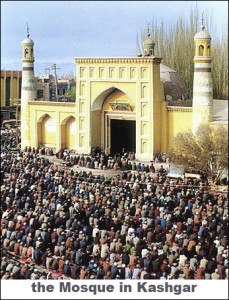

Islamism

Islam was first introduced in China during the Tang Dynasty when a large number of Muslim merchants came from West Asia to trade in China. During the 10th century, Satuk Bugera Khan, King of the Karahan Empire based in Kashgar and Artux, converted to Islam. In the early 11th century, the Karahan army conquered the Khotan Kingdom and changed the official local religion to Islam, converting many of the local people in the process. By the 13th century, along with the large-scale expedition of the Mongolian armed forces, a large number of Persians and Arabs who followed Islam came to China and mixed with the locals, gradually forming a unique Chinese Muslim community.

Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism from Persia and Nestorianism from East Rome also made their way into China. All of these religions entered China via the Silk Road during the Tang Dynasty.

Sugar Processing

China began growing sugar cane during the “Spring and Autumn and the Warring States Period” (770 B.C. – 221 B.C.). However, Chinese people only ever chewed the raw canes or extracted juice from them. According to historical records, the technology for sucrose brewing had appeared in India as early as the Western Han Dynasty (in China). While trading on the Silk Road, Han people saw the end-product (the refined sugar) being sold and wanted to learn how to make it themselves.

Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty sent an envoy to ancient India to study the technology behind sugar-refinement.

Glass

The common opinion is that Sumerians living in Mesopotamia invented glass around about 5000 B.C. By 2000 B.C. Phoenicians living on the west coast of modern-day Lebanon and Syria had passed this method of making glass on to the ancient Egyptians, who then improved and perfected the method. As early as 1000 B.C. glass was introduced into the Western Regions in Xinjiang. With the establishment of the Silk Road in the 5th century, the technology of glass-manufacture was finally introduced in China by Dayuezhi traders from Central Asia.

Cotton

More than several dozen species of plant were introduced into China via the Silk Road, including grapes, cucumber, walnuts and garlic. In particular the introduction of cotton had a far-reaching impact on China’s economic development and Chinese people’s livelihoods.

Cotton was originally grown in India and Africa. The Xinjiang region in China was the first place in the country that started growing cotton. By the Eastern Han Dynasty, Xinjiang was already engaged in growing cotton, spinning cotton wool and weaving cotton fabrics.

Before cotton was introduced into China, Chinese clothing was predominantly made of fur, silk and linen. During the Tang Dynasty, the Tang troops conquered Gaochang (in the Tarim basin) and brought back cotton seeds to grow further inland. By the Yuan Dynasty, cotton had become the main material used to make clothing in China.

No matter which direction they were going in, plenty of products and technologies made their way to different ethnic groups thanks to the Silk Road. All of these groups benefited a lot from the different arts and technologies they were exposed to.

Xuanzang(602 – 664), a Chinese Buddhist monk and scholar, who mainly studied and focused his efforts upon the interaction between China and India during the Tang Dynasty.

Major Cities along the Silk Road

In China, the Silk Road passes through three provinces – Shaanxi, Gansu and Xinjiang. There are many big cities and towns in these provinces. Most of them still play an important role in China today.

Xi’an

The Silk Road begins in the ancient capital city of Chang’an, which is now known as Xi’an. As early as the Palaeolithic Age the original settlers thrived in the area around Xi’an, leaving many historical remains, such as the Site of the Lantian Man. During the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th century B.C. – 771 B.C.), the capital city of Haojing was located in the northwest part of Xi’an. When the Western Han Dynasty was established, the imperial court chose Chang’an as its capital city. From then one, for more than a thousand years, Chang’an was the capital city and served as the capital of twenty-one different dynasties. Among these dynasties, the Han Dynasty, the Sui Dynasty and the Tang Dynasty were known to be very powerful and prosperous regimes in Chinese history.

The Silk Road begins in the ancient capital city of Chang’an, which is now known as Xi’an. As early as the Palaeolithic Age the original settlers thrived in the area around Xi’an, leaving many historical remains, such as the Site of the Lantian Man. During the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th century B.C. – 771 B.C.), the capital city of Haojing was located in the northwest part of Xi’an. When the Western Han Dynasty was established, the imperial court chose Chang’an as its capital city. From then one, for more than a thousand years, Chang’an was the capital city and served as the capital of twenty-one different dynasties. Among these dynasties, the Han Dynasty, the Sui Dynasty and the Tang Dynasty were known to be very powerful and prosperous regimes in Chinese history.

When the Silk Road was first opened during the reign of Emperor Wu of the Western Han Dynasty, Chang’an became larger and richer. It covered an area of about thirty-six square kilometres and had twelve gates and eight major streets. At the time, the city was four times the size of the capital city of Rome. Export goods, such as raw silk, satin and leather from all over the country, were first shipped to Chang’an. There they were wrapped and packed with painted linen and leather into bundles by foreign merchants, then shipped out on huge foreign caravans to westbound cities on the Silk Road.

During the Tang Dynasty, Chang’an enjoyed the period of greatest economic prosperity in its history. The whole city was 2.4 times larger than it had been during the Han Dynasty. The city’s layout was like a chessboard, and the imperial palace was surrounded by rings of outer city walls. The uniform residential buildings and the efficient water supply network reflected how advanced society in this city had become. During that time, Chang’an truly deserved the honour of being called an international metropolis. According to historical records, over three hundred countries and regions sent envoys to Chang’an to establish diplomatic connections.

When Buddhism was first introduced into mainland China, many Buddhist temples were built in Chang’an. At around about the same time, a few Muslim mosques were also erected in the city.

Tianshui

Located in the southeast of Gansu Province, Tianshui was known as Qinzhou in ancient times. When Emperor Yingzheng, the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty (221 B.C. – 207 B.C.), unified China in 221 B.C., Qinzhou was officially established as an administrative unit. In 114 B.C., during the Western Han Dynasty, the Emperor Wu set Tianshui up as a county.

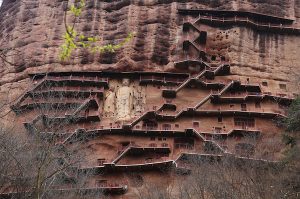

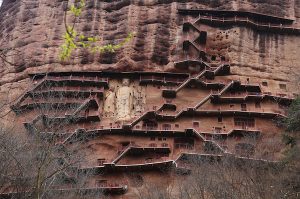

Thanks to the opening of the Silk Road, Tianshui became one of the major towns for trade. Not only that, it also kept many precious records of the eastward spread of foreign cultures coming into China. For example, the famous Maijishan Grottoes, which are sometimes known collectively as the “Oriental Sculpture Museum”, are in Tianshui.

As one of the four major groups of grottoes in China, the Maijishan Grottoes have more than 1600 years of history behind them. The digging of the caves started during the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420 – 589 A.D.). Now the Maijishan Grottoes boast ownership of one hundred and ninety-four caves with more than seven thousand two hundred stone statues and one thousand three hundred square metres of mural paintings in them.

As one of the four major groups of grottoes in China, the Maijishan Grottoes have more than 1600 years of history behind them. The digging of the caves started during the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420 – 589 A.D.). Now the Maijishan Grottoes boast ownership of one hundred and ninety-four caves with more than seven thousand two hundred stone statues and one thousand three hundred square metres of mural paintings in them.

Apart from the Maijishan Grottoes, there are also many other similar grottoes in China. For example, there are grottoes in the Huagai Temple, the Gangu valley, the Wooden Ladder Temple and the Meditation Temple. All of these grottoes make up the Hexi Corridor or the “Grotto Corridor” on the Silk Road.

Wuwei

Wuwei is located in the middle of Gansu Province. It belonged to the Dayuezhi Kingdom two thousand years ago. During the early Western Han Dynasty, the Xiongnu defeated the Dayuezhi and occupied this area. In 121 B.C. Emperor Wu sent his favourite General, named Huo Qubing, to fight against the Xiongnu and was rewarded with a colossal victory. The entire Hexi Corridor was incorporated into the territory of the Western Han Dynasty. Later on, four administrative counties were set up there – Wuwei, Jiuquan, Zhangye and Dunhuang.

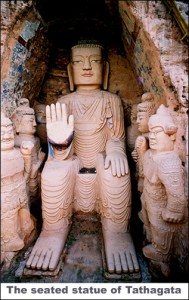

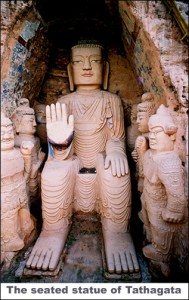

Located in the south of Wuwei city, the Tiantishan Grotto (also known as the Temple of the Giant Buddha) was built by the late Liang administration when the Sixteen Kingdoms ruled in succession in the North of China alongside the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317 – 420 A.D.).

The seated statue of the Tathagata Buddha is in the main structure known as the “Giant Buddha Cave”. It has been so meticulously carved that its vivid facial expression makes it seem almost like it’s alive.

Zhangye

Zhangye is located in the northwest of Gansu Province. In 121 B.C., during the Western Han Dynasty, Zhangye was set up as a county. The name meant “the Han Court’s arms open to link up with the Western Regions”. After it was established as a county, the imperial court implemented a large scale immigration and land reclamation program in Zhangye. They stationed their troops there and helped develop local agriculture.

During the Wei and Jin periods, Juqu Mengxun, a military commander of the Xiongnu ethnic group, established the Northern Liang Kingdom (397or401 – 439) and designated Zhangye as its capital. He supported Confucianism and expanded exchanges with the Western Regions. He also promoted Buddhism and authorized the building of many grottoes.

During the Wei and Jin periods, Juqu Mengxun, a military commander of the Xiongnu ethnic group, established the Northern Liang Kingdom (397or401 – 439) and designated Zhangye as its capital. He supported Confucianism and expanded exchanges with the Western Regions. He also promoted Buddhism and authorized the building of many grottoes.

During the Northern Song Dynasty (960 – 1127), the Dangxiang ethnic group established the Western Xia Kingdom (1038 – 1227) and built a large Buddhist temple named the Big Buddha Temple. There is a Shakyamuni Nirvana reclining statue here which has a wooden base and is made of clay that has been painted gold. It is the largest reclining Buddha statue in the world.

Dunhuang

The name Dunhuang was adopted during the Western Han Dynasty and it means “large and prosperous”. Since its official incorporation as a county in 111 B.C., Dunhuang has been habitually regarded as the border between Han territory and the Western Regions. Since it was the most important transportation hub on the Silk Road, Dunhuang became a large commercial trade town. During the Tianbao Period (742 – 756) of the Tang Dynasty, the population of Dunhuang increased to approximately one hundred and twenty thousand.

Dunhuang is also well known for its Buddhist Grottoes. There are three grotto sites in Dunhuang – the Mogao Grottoes (Thousand Buddha Caves), the Yulin Grottoes (Ten Thousand Buddha Valley) and the West Thousand Buddha Caves. The Mogao Grottoes are the most famous and were listed as a world heritage site by UNESCO in 1987.

Turpan

Lying in the Tarim basin to the east of the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang Province, Turpan has been the transportation hub linking mainland China to central Asia, as well as southern Xinjiang to northern Xinjiang, since ancient times. It naturally became an important town along the Silk Road.

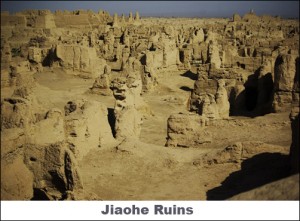

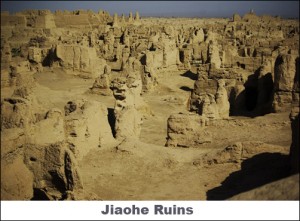

During the Western Han Dynasty, Turpan was controlled by the former Gushi Kingdom. Between 99 B.C. and 72 B.C., wars frequently broke out between the Western Han people and the Xiongnu people, who were competing for control of the Western Regions. When the Xiongnu ultimately failed, the Gushi Kingdom surrendered to the Han Dynasty and was formally incorporated into the Western Han’s territory. The Western Han Dynasty divided the former Gushi territory into eight counties and ruled them all separately. The former Gushi citizens were allocated a place in the Turpan Basin, with Jiaohe as their capital city.

Jioahe was built on a large island in the middle of a river. This formed a natural moat around the city that helped to defend it. There were steep cliffs on all sides of the river. The city was abandoned in the 13th century, and the river has long since dried up and has been gone for hundreds of years.

During the Early Liang Period (320-376 A.D.), Gaochang County was set up in the Turpan region. During the Northern Wei Period (386-534 A.D.), the Rouran ethnic people established the Gaochang Kingdom. In 450 A.D., after the former Gushi Kingdom was eliminated by the Northern Liang Dynasty, Gaochang city became the political, economic and cultural centre of the Turpan Basin. In 640 A.D., the Tang Dynasty unified the Turpan area once again and Gaochang was changed into a county of the Tang imperial court.

The surviving Gaochang ruins were built when it was ruled by the Uighurs but were constructed on the bases of the original Tang structures. There are many cultural relics in this city, such as the Manichaean mural paintings, the documents from the Uighur period and the Buddhist murals, statues and documents, all of them in different languages.

The Turpan region is also one of the epicentres of Uygur culture. Ancestors of the modern-day Uygur ethnic minority were ancient Uighurs, who entered the Western Regions during the 9th century and settled down in Turpan. The Uygur culture has its own uniquely charming styles of art, including their own styles of music, dance, costumes, rituals and architecture.

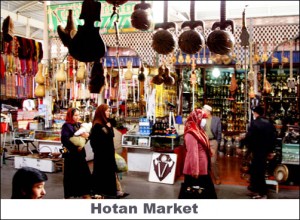

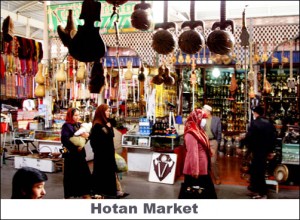

Hotan

Hotan, sometimes referred to as Hetian, is in the south of Xinjiang Province, on the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert. Hotan was one of the first areas where Buddhism was introduced in China. As early as the 1st century B.C. Buddhism was introduced in Khotan (Hotan’s ancient name) and it subsequently became the first centre of Buddhist culture in the Western Regions. Khotan was known back then as “Khotan the Buddhist Kingdom”. However, with the eastward dissemination of Islam in the 11th century, people in the Khotan region gradually converted to Islam instead.

As an important town on the Silk Road, Hotan was one of the first sericulture and silk production centres in Xinjiang. With fertile land and adequate sunshine, the climate in Hotan was well-suited for growing and producing silk.

The most famous specialty commodity from Hotan was and still is jade. As early as the Neolithic Period, Hotan locals mined jade in Mt. Kunlun. The trade route from Hotan used for transporting jade was established 1000 years before the Silk Road even existed. This route was named the Jade Road and is often considered the predecessor of the Silk Road.

Located in the Taklimakan Desert, one hundred and fifty kilometres north of Hotan, you’ll find the famous Niya Ruins. The Niya Ruins were first discovered in 1901 by Marc Aurel Stein, a Hungarian archaeologist who had British citizenship. However, at the time he was unable to identify the ruins and it wasn’t until the 1930s that they were finally identified as the former capital city of the Jingjue Kingdom.

Kashgar

Kashgar sits on the southwest edge of Xinjiang and is China’s westernmost city. Many different regimes have controlled Kashgar at different points in its history. During the Tang Dynasty, Kashgar became an important military stronghold for the Tang imperial court. After the Tang Dynasty, Kashgar was ruled by the Karahan Empire (840-1212) and the West Liao Kingdom (1124-1218) successively. During Genghis Khan’s successful expedition westward, he conquered Kashgar and made it is his second son’s fiefdom.

From the Han Dynasty onwards, the southern, northern and central parts of the Silk Road all passed through Kashgar. Kashgar was the main distribution centre and the largest transport hub on the Silk Road. Its location and history heavily influenced the development of Kashgar’s unique layout and style. The city looks like a combination of an ancient city from central Asia and west Asia. The old parts of Kashgar are the only surviving districts in China that show what cities in the ancient Western Regions would have looked like.

Enjoy the magnificent landscape and discover more culture along the Silk road on our travel: Explore the Silk Road in China

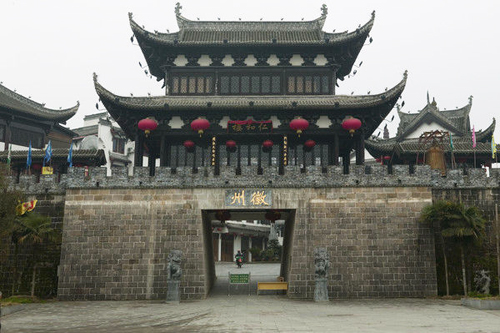

As a famous village in Huizhou, Xidi was once occupied by many rich Hui merchants. They wanted to build luxury houses to show off their wealth. But the strict hierarchy of society had restrictions on construction which specifically affected people of a lower social class. So the merchants were only able to choose the best materials and utilize the most sophisticated workmanship when building their place of residence. The memorial archway—built in 1578 by Hu Wenguang, who was a high-ranking official during the Ming Dynasty—is a good representation of the Hui-style of stone carving. The best example of Hui brick sculpture is in the house of another Ming official, which is in a place called the West Garden.

As a famous village in Huizhou, Xidi was once occupied by many rich Hui merchants. They wanted to build luxury houses to show off their wealth. But the strict hierarchy of society had restrictions on construction which specifically affected people of a lower social class. So the merchants were only able to choose the best materials and utilize the most sophisticated workmanship when building their place of residence. The memorial archway—built in 1578 by Hu Wenguang, who was a high-ranking official during the Ming Dynasty—is a good representation of the Hui-style of stone carving. The best example of Hui brick sculpture is in the house of another Ming official, which is in a place called the West Garden.

There is no doubt that the success of the

There is no doubt that the success of the  When talking about Hui culture, it is inevitable that one should make mention of the fantastic Hui architecture. Not to mention that the Hui architecture is the most extant and well preserved type of Hui art that we can see nowadays.

When talking about Hui culture, it is inevitable that one should make mention of the fantastic Hui architecture. Not to mention that the Hui architecture is the most extant and well preserved type of Hui art that we can see nowadays.

The Silk Road begins in the ancient capital city of Chang’an, which is now known as Xi’an. As early as the Palaeolithic Age the original settlers thrived in the area around Xi’an, leaving many historical remains, such as the Site of the Lantian Man. During the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th century B.C. – 771 B.C.), the capital city of Haojing was located in the northwest part of Xi’an. When the Western Han Dynasty was established, the imperial court chose Chang’an as its capital city. From then one, for more than a thousand years, Chang’an was the capital city and served as the capital of twenty-one different dynasties. Among these dynasties, the Han Dynasty, the Sui Dynasty and the Tang Dynasty were known to be very powerful and prosperous regimes in Chinese history.

The Silk Road begins in the ancient capital city of Chang’an, which is now known as Xi’an. As early as the Palaeolithic Age the original settlers thrived in the area around Xi’an, leaving many historical remains, such as the Site of the Lantian Man. During the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th century B.C. – 771 B.C.), the capital city of Haojing was located in the northwest part of Xi’an. When the Western Han Dynasty was established, the imperial court chose Chang’an as its capital city. From then one, for more than a thousand years, Chang’an was the capital city and served as the capital of twenty-one different dynasties. Among these dynasties, the Han Dynasty, the Sui Dynasty and the Tang Dynasty were known to be very powerful and prosperous regimes in Chinese history. As one of the four major groups of grottoes in China, the Maijishan Grottoes have more than 1600 years of history behind them. The digging of the caves started during the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420 – 589 A.D.). Now the Maijishan Grottoes boast ownership of one hundred and ninety-four caves with more than seven thousand two hundred stone statues and one thousand three hundred square metres of mural paintings in them.

As one of the four major groups of grottoes in China, the Maijishan Grottoes have more than 1600 years of history behind them. The digging of the caves started during the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420 – 589 A.D.). Now the Maijishan Grottoes boast ownership of one hundred and ninety-four caves with more than seven thousand two hundred stone statues and one thousand three hundred square metres of mural paintings in them.

During the Wei and Jin periods, Juqu Mengxun, a military commander of the Xiongnu ethnic group, established the Northern Liang Kingdom (397or401 – 439) and designated Zhangye as its capital. He supported Confucianism and expanded exchanges with the Western Regions. He also promoted Buddhism and authorized the building of many grottoes.

During the Wei and Jin periods, Juqu Mengxun, a military commander of the Xiongnu ethnic group, established the Northern Liang Kingdom (397or401 – 439) and designated Zhangye as its capital. He supported Confucianism and expanded exchanges with the Western Regions. He also promoted Buddhism and authorized the building of many grottoes.

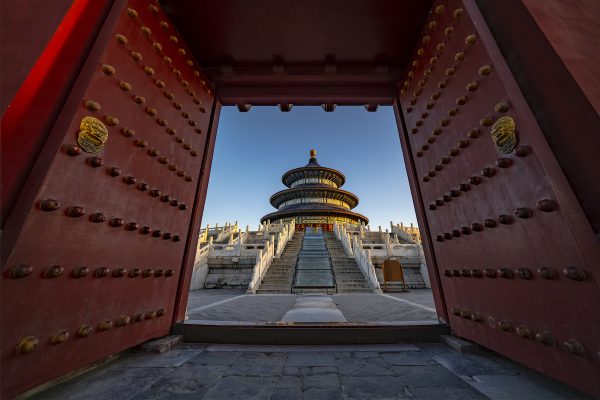

The Temple of the God (Creator) of Agriculture was the site of imperial sacrifices dedicated to the cult of Shennong, the Holy Farmer. It is located in the southern part of the city, directly to the west of the Temple of Heaven, and occupies a total area of three-square kilometres.

The Temple of the God (Creator) of Agriculture was the site of imperial sacrifices dedicated to the cult of Shennong, the Holy Farmer. It is located in the southern part of the city, directly to the west of the Temple of Heaven, and occupies a total area of three-square kilometres.

A great number of plays in the Huangmei Opera style have been performed and have achieved great popularity, including plays such as the Goddess’ Marriage, the Emperor’s Female Son-in-law, the Cower Herd and the Weaving Girl, the Couple Watching Lanterns, and Picking up the Green feed for the Pigs. Their themes and content are generally taken from folk legend and normal routine life.Huangmei Opera is well known for being particularly expressive and has a rich lingering charm, melodious music and graceful movements. The dialogue is easy to understand, and is imbued with the realistic essence of routine life and the flavour of traditional folk songs. Therefore, it is very mellifluous and pleasing to the ears.

A great number of plays in the Huangmei Opera style have been performed and have achieved great popularity, including plays such as the Goddess’ Marriage, the Emperor’s Female Son-in-law, the Cower Herd and the Weaving Girl, the Couple Watching Lanterns, and Picking up the Green feed for the Pigs. Their themes and content are generally taken from folk legend and normal routine life.Huangmei Opera is well known for being particularly expressive and has a rich lingering charm, melodious music and graceful movements. The dialogue is easy to understand, and is imbued with the realistic essence of routine life and the flavour of traditional folk songs. Therefore, it is very mellifluous and pleasing to the ears.