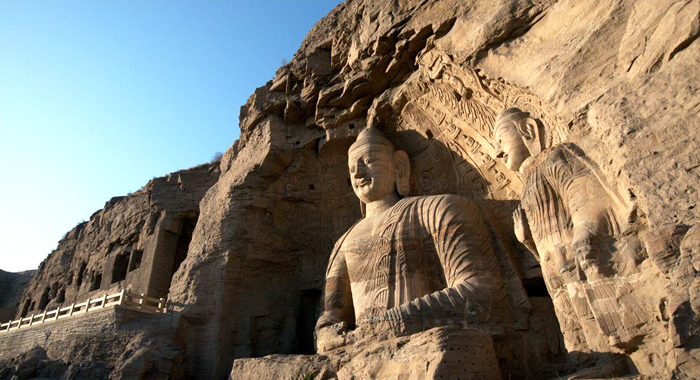

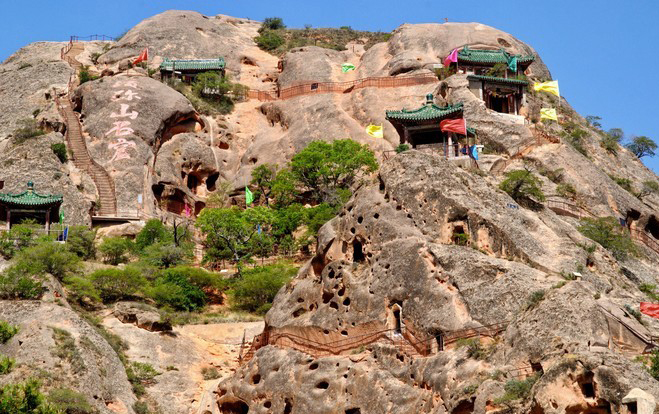

Dating all the way back to the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535), the Xumi Mountain Grottoes are classed as one of the 10 most culturally significant Buddhist grottoes in China. On the eastern edge of Mount Xumi, eight red sandstone cliffs are speckled with over 160 hand-carved caves, 70 of which contain magnificent carvings, colourful murals, spectacular frescoes, and delicate inscriptions. The site’s star attraction is a 20-metre (65 ft.) tall statue of Maitreya[1] Buddha, who looks wistfully out into the surrounding countryside. To put that into perspective, it’s about four times as tall as an adult giraffe! However, there’s more to this scenic site than just one (very) big Buddha.

Although the complex was originally built during the Northern Wei Dynasty, its construction spans five dynastic eras, as it was periodically added to right up until the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The grottoes are located along the Silk Road, which was integral to the dissemination of Buddhism in China. Their location along this trade route is palpable in the Indian and Central Asian motifs that appear in many of the sculptures and paintings. Grotto No. 33, with its square layout and partition wall punctuated by three portals, is a typical example of this, as it greatly resembles a traditional Indian temple. As time went on, the grottoes that were added and the art within them became distinctly more Chinese in style, demonstrating the gradual Sinification of Buddhism in China.

The mountain’s name, “Xumishan” or “Mount Xumi”, is actually the Chinese variation of the Sanskrit word for Mount Sumeru, the cosmic mountain that rests at the centre of the universe according to Buddhism. It was originally known as Mount Fengyi, but this spiritual rebranding was thought to be a ploy to encourage more monks to travel to the site, live there, and help carve more grottoes. Talk about false advertising! Many of the caves have virtually no decorative elements and it is believed that they were used to house the resident monks.

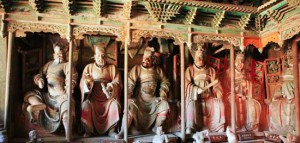

Nowadays the site has been separated into five main areas: Dafo or “Big Buddha” Tower, Zisun Palace, Yuanguang Temple, Xiangguo Temple, and Taohua Cave. Grottoes No. 45 and 46 are some of the most noteworthy, since they contain the largest number of statues, 40 of which are taller than the average person. Grotto No. 14 is believed to be the oldest and contains statues and paintings dating back to the early Northern Wei Dynasty. Though primitive in design and colour, they are resplendent in their simplistic beauty. Much of the statuary in this grotto resembles that of the famous Yungang Grottoes in Shanxi province and the Mogao Caves in Gansu province.

Unfortunately, in spite of being designated a National Level Cultural Relic Protected Site in 1982, the Xumi Mountain Grottoes are currently at risk. Wind and sand erosion, unstable rock beds, earthquakes, and vandalism have already caused irreparable damage to the caves, and a recent study suggests that only about 10 per cent of them are in decent condition. The extent of the damage has led to the grottoes being listed as one of the Top 100 Most Endangered Historical Sites in the world. So be sure to catch them while you can, or risk missing out on this treasure trove of ancient Buddhist art!

[1] Maitreya: In the Buddhist tradition, Maitreya is a bodhisattva who will appear on Earth sometime in the future and achieve complete enlightenment. He will be the successor to the present Buddha, Gautama Buddha, and is thus regarded as a sort of future Buddha.

Nowadays, though the legendary tree unfortunately no longer stands, parts of it are now preserved in the stupa that rests in the Great Hall of the Golden Roof. Before the 1950s, the monastery supported a colossal 3,600 monks, although now there are only about 400. The majority are from the Tibetan ethnic minority, with the rest representing a mixture of Mongol, Yugur, and Han people. These monks are divided into four monastic colleges or “dratsang”: the Debate College, the Tantric College, the Medical College, and the Kalachakra

Nowadays, though the legendary tree unfortunately no longer stands, parts of it are now preserved in the stupa that rests in the Great Hall of the Golden Roof. Before the 1950s, the monastery supported a colossal 3,600 monks, although now there are only about 400. The majority are from the Tibetan ethnic minority, with the rest representing a mixture of Mongol, Yugur, and Han people. These monks are divided into four monastic colleges or “dratsang”: the Debate College, the Tantric College, the Medical College, and the Kalachakra

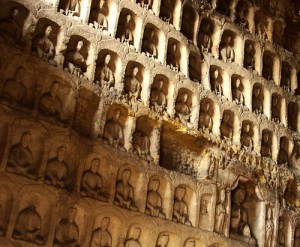

The 70 caves that make up the complex were hand-carved into the cliff-face of Linsong Mountain, about 65 kilometres (40 mi) north of Zhangye, and can be separated into 7 grotto groups: Mati Temple, Shenguo Temple, Qianfo or “Thousand Buddha” Caves, Jinta or “Golden Tower” Temple, Upper Guanyin Cave, Middle Guanyin Cave, and Lower Guanyin Cave.

The 70 caves that make up the complex were hand-carved into the cliff-face of Linsong Mountain, about 65 kilometres (40 mi) north of Zhangye, and can be separated into 7 grotto groups: Mati Temple, Shenguo Temple, Qianfo or “Thousand Buddha” Caves, Jinta or “Golden Tower” Temple, Upper Guanyin Cave, Middle Guanyin Cave, and Lower Guanyin Cave. With the snow-capped Qilian Mountains behind and the jade-hued grasslands stretching out in front, the scenery surrounding the Mati Temple is unparalleled in its natural beauty. It rests just outside of a small village that is also conveniently named Mati. It seems those hoof-prints really made their mark after all! Since the village is populated primarily by members of the Yugur ethnic minority, visitors to the area are also welcome to indulge in a few Yugur customs. From enjoying a cup of pure chang, a locally brewed wine made from barley, to sampling sumptuous chunks of traditional stewed lamb, you won’t want to miss out on a chance to connect with these gentle, nomadic people. If you want to extend your stay, you can even spend a few days in one of their yurts and take part in a few horse rides. Just don’t walk behind the horses, or you may end up with a sacred hoof-print on your head!

With the snow-capped Qilian Mountains behind and the jade-hued grasslands stretching out in front, the scenery surrounding the Mati Temple is unparalleled in its natural beauty. It rests just outside of a small village that is also conveniently named Mati. It seems those hoof-prints really made their mark after all! Since the village is populated primarily by members of the Yugur ethnic minority, visitors to the area are also welcome to indulge in a few Yugur customs. From enjoying a cup of pure chang, a locally brewed wine made from barley, to sampling sumptuous chunks of traditional stewed lamb, you won’t want to miss out on a chance to connect with these gentle, nomadic people. If you want to extend your stay, you can even spend a few days in one of their yurts and take part in a few horse rides. Just don’t walk behind the horses, or you may end up with a sacred hoof-print on your head!

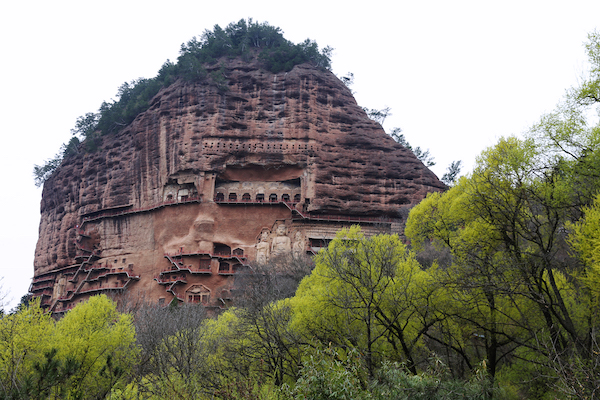

The mountain itself sits at an altitude of 1,700 metres (5,577 ft.) and is named “Maiji”, meaning “wheat”, “corn”, or “grain stack”, due to its unusual appearance. It is tall in the middle, narrow at the bottom, and completely flat on the top, meaning it resembles a stack of wheat. So be careful when you take photographs of this scenic spot, or they might come out a little grainy! The caves are separated by number, with numbers 1 to 50 on the western cliff-face and numbers 51-191 on the eastern cliff-face.

The mountain itself sits at an altitude of 1,700 metres (5,577 ft.) and is named “Maiji”, meaning “wheat”, “corn”, or “grain stack”, due to its unusual appearance. It is tall in the middle, narrow at the bottom, and completely flat on the top, meaning it resembles a stack of wheat. So be careful when you take photographs of this scenic spot, or they might come out a little grainy! The caves are separated by number, with numbers 1 to 50 on the western cliff-face and numbers 51-191 on the eastern cliff-face. Construction of the grottoes reached its peak during the Northern Wei (386-535), Western Wei (535–557), and Northern Zhou (557-581) dynasties, but continued well into the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, representing over 1,000 years’ worth of effort and artistry. The earlier caves are far more simplistic in design and mainly feature a seated Buddha flanked by bodhisattvas

Construction of the grottoes reached its peak during the Northern Wei (386-535), Western Wei (535–557), and Northern Zhou (557-581) dynasties, but continued well into the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, representing over 1,000 years’ worth of effort and artistry. The earlier caves are far more simplistic in design and mainly feature a seated Buddha flanked by bodhisattvas The bodhisattvas who usually accompany Amitābha are Avalokitesvara on his right and Mahasthamaprapta on his left. Avalokitesvara is the most identifiable, as he is typically depicted with an image of Amitābha on his headdress and a small water flask in his hands. In a few more hundred years, Avalokitesvara will change genders and eventually reappear in the grottoes as the bodhisattva of mercy, known as Guanyin. That being said, when it comes to eternal enlightenment, it doesn’t really matter if you’re a man or a woman! Other statues include those of the historical Shakyamuni

The bodhisattvas who usually accompany Amitābha are Avalokitesvara on his right and Mahasthamaprapta on his left. Avalokitesvara is the most identifiable, as he is typically depicted with an image of Amitābha on his headdress and a small water flask in his hands. In a few more hundred years, Avalokitesvara will change genders and eventually reappear in the grottoes as the bodhisattva of mercy, known as Guanyin. That being said, when it comes to eternal enlightenment, it doesn’t really matter if you’re a man or a woman! Other statues include those of the historical Shakyamuni