The Bund has become something of an emblem for the city of Shanghai and is widely considered to be its most well-known tourist attraction. Its name serves as a testament to the city’s cosmopolitan nature, as it was coined by British expats and derives from the Persian word “band”, which means embankment or levee. As a harbour city, Shanghai has seen more foreign merchants, visitors, and residents over the years than some Chinese cities will see in their lifetime. Yet these expats weren’t just content to live in the city; they had to make their mark on it too!

Traditionally speaking, the Bund centres on a stretch of Zhongshan Road that runs alongside the Huangpu River, beginning at Yan’an Road in the south and ending at Waibaidu Bridge in the north. Futuristic skyscrapers belonging to the Pudong District rise up on the east bank, while the west bank is flanked by 52 buildings dating back to the 19th century. These distinctly colonial constructions adhere to a variety of architectural styles, including Eclecticist, Romanesque Revival, Gothic Revival, Renaissance Revival, Baroque Revival, Neo-Classical, Beaux-Arts, and a number in the Art Deco style. It’s a History of Art major’s paradise; or nightmare, depending upon their tastes!

After the First Opium War (1839-1842), China signed an agreement known as the Treaty of Nanking, which named Shanghai as one of five Chinese seaports to be opened up to unrestricted foreign trade. In 1846, Great Britain established its consulate on the Bund and, not long thereafter, several foreign countries followed suite. The area surrounding it became one of the first foreign concessions in Shanghai and, when the British concession was combined with the American one in 1863, it became known as the Shanghai International Settlement.

In the early 20th century, it swiftly evolved into Shanghai’s political, economic, and cultural centre, with numerous banks, businesses, hotels, newspaper offices, and luxurious gentleman’s clubs setting up on its expanse. Granite from Japan, marble from Italy, fixtures from England; all of the finest materials were imported into Shanghai in order to construct these lavish buildings. In short, no expense was spared! During the 1920s, it became the hottest piece of real estate in the city and companies from across the globe scrambled to make their mark on the place. From Belgium and France right through to Russia and Japan, foreign countries were eager to carve out their own little slice of the Bund.

Nowadays it hosts some of the most noteworthy buildings in Shanghai, including the Shanghai Club (No. 2), the HSBC Building (No. 12), the Customs House (no. 13), Sassoon House (No. 20), and the Bank of China Building (No. 23). The Shanghai Club was originally constructed in 1861 and was the principal social club for British expats living in Shanghai. However, it was torn down and replaced with a building of more neoclassical design in 1910. Its opulent interior incorporates black and white flooring made entirely of marble and an entrance staircase crafted from imported white Sicilian marble. Talk about extravagant! Its lavish décor meant it was easily converted into the Waldorf-Astoria Shanghai Hotel in 2010.

Although Building No. 12 now belongs to the Shanghai Pudong Development Bank, it is better known for having once been the Shanghai headquarters of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC). It was built in 1923 according to the neoclassical style and was, at the time of its construction, the second largest building in the world. By some bizarre coincidence, it now faces the Shanghai Tower in the Pudong District, which is currently the world’s second tallest building. Hopefully the area isn’t always doomed to be second best!

Its central dome and six white columns are reminiscent of traditional Greek style architecture, and its interior has been lavishly decorated with marble and monel. According to a local saying at the time, it was known as “the most luxurious building between the Suez Canal and the Bering Strait”. It is perhaps most famous for its stunning ceiling mosaics, which have been fully restored and can be viewed from inside the entrance hall.

Alongside the HSBC Building, the Shanghai Customs House is perhaps the most iconic building on the Bund, as it features a large clock tower that was constructed in the style of England’s Big Ben. It was built in 1927 on the site of an older Chinese-style customs house and follows a neoclassical design. As with the HSBC Building, it features large stone columns stretching from the third to the sixth storey, which resemble those of traditional Greek style architecture.

The nearby Sassoon House was masterminded by Victor Sassoon in 1929, who had invested huge amounts of capital into Shanghai at the time. Known to many as the “Rothschilds of the East”, the Sassoon Family were an extraordinarily wealthy Iraqi merchant family whose business eventually extended from Central Asia all the way to China. This colossal 13-storey mansion features elaborately decorated eaves and a distinctively green pyramidal roof topping its eastern façade. It is now part of the Peace Hotel and is still renowned for the live jazz band in its café. With that in mind, a trip to the Sassoon House is sure to clear up those homesick blues!

The nearby Sassoon House was masterminded by Victor Sassoon in 1929, who had invested huge amounts of capital into Shanghai at the time. Known to many as the “Rothschilds of the East”, the Sassoon Family were an extraordinarily wealthy Iraqi merchant family whose business eventually extended from Central Asia all the way to China. This colossal 13-storey mansion features elaborately decorated eaves and a distinctively green pyramidal roof topping its eastern façade. It is now part of the Peace Hotel and is still renowned for the live jazz band in its café. With that in mind, a trip to the Sassoon House is sure to clear up those homesick blues!

Its next-door neighbour, the Bank of China Building, was rather unsurprisingly the original headquarters of the Bank of China. It was built in 1937 and is perhaps most well-known for its somewhat stunted appearance, which is often attributed to Victor Sassoon’s insistence that no other building on the Bund could be taller than his. Evidently Sassoon had what we’d like to call “short-building syndrome”!

Originally the Bund was flanked by numerous bronze statues of foreign dignitaries, but these were all removed when the Communist Party took over in 1949. Today only one statue remains, that of Chen Yi, the first Communist mayor of Shanghai. This statue and Huangpu Park, which lies at the Bund’s northernmost end, are frequented by locals of all ages and make for an ideal place to relax. A number of pleasure cruises still operate from the Bund’s wharves and typically take visitors down to an estuary of the Yangtze River, which altogether is about a 3 hour round trip. So if you want to experience what life was like for Shanghai’s wealthy expats, perhaps a luxury river cruise is on the cards!

Join our travel to visit the Bund in Shanghai: Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages

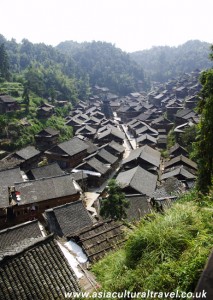

Yintan has also managed to maintain a few ancient opera stages, where performances of all kinds take place. From hearty dancing to piercing opera, the village locals really know how to enjoy the simple things in life! Unlike many other Dong communities, where youths only don their traditional outfits on festival occasions, almost all of the villagers in Yintan regularly wear their characteristic indigo-coloured clothes all year round. These clothes are handmade using the ancient tradition of cloth weaving and dyeing, which was passed on to them by their ancestors.

Yintan has also managed to maintain a few ancient opera stages, where performances of all kinds take place. From hearty dancing to piercing opera, the village locals really know how to enjoy the simple things in life! Unlike many other Dong communities, where youths only don their traditional outfits on festival occasions, almost all of the villagers in Yintan regularly wear their characteristic indigo-coloured clothes all year round. These clothes are handmade using the ancient tradition of cloth weaving and dyeing, which was passed on to them by their ancestors.

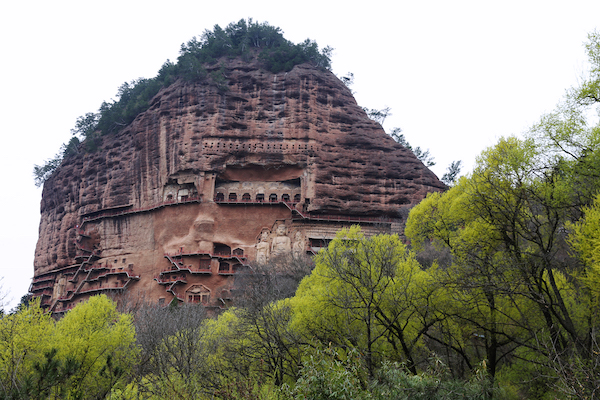

The 70 caves that make up the complex were hand-carved into the cliff-face of Linsong Mountain, about 65 kilometres (40 mi) north of Zhangye, and can be separated into 7 grotto groups: Mati Temple, Shenguo Temple, Qianfo or “Thousand Buddha” Caves, Jinta or “Golden Tower” Temple, Upper Guanyin Cave, Middle Guanyin Cave, and Lower Guanyin Cave.

The 70 caves that make up the complex were hand-carved into the cliff-face of Linsong Mountain, about 65 kilometres (40 mi) north of Zhangye, and can be separated into 7 grotto groups: Mati Temple, Shenguo Temple, Qianfo or “Thousand Buddha” Caves, Jinta or “Golden Tower” Temple, Upper Guanyin Cave, Middle Guanyin Cave, and Lower Guanyin Cave. With the snow-capped Qilian Mountains behind and the jade-hued grasslands stretching out in front, the scenery surrounding the Mati Temple is unparalleled in its natural beauty. It rests just outside of a small village that is also conveniently named Mati. It seems those hoof-prints really made their mark after all! Since the village is populated primarily by members of the Yugur ethnic minority, visitors to the area are also welcome to indulge in a few Yugur customs. From enjoying a cup of pure chang, a locally brewed wine made from barley, to sampling sumptuous chunks of traditional stewed lamb, you won’t want to miss out on a chance to connect with these gentle, nomadic people. If you want to extend your stay, you can even spend a few days in one of their yurts and take part in a few horse rides. Just don’t walk behind the horses, or you may end up with a sacred hoof-print on your head!

With the snow-capped Qilian Mountains behind and the jade-hued grasslands stretching out in front, the scenery surrounding the Mati Temple is unparalleled in its natural beauty. It rests just outside of a small village that is also conveniently named Mati. It seems those hoof-prints really made their mark after all! Since the village is populated primarily by members of the Yugur ethnic minority, visitors to the area are also welcome to indulge in a few Yugur customs. From enjoying a cup of pure chang, a locally brewed wine made from barley, to sampling sumptuous chunks of traditional stewed lamb, you won’t want to miss out on a chance to connect with these gentle, nomadic people. If you want to extend your stay, you can even spend a few days in one of their yurts and take part in a few horse rides. Just don’t walk behind the horses, or you may end up with a sacred hoof-print on your head!

The mountain itself sits at an altitude of 1,700 metres (5,577 ft.) and is named “Maiji”, meaning “wheat”, “corn”, or “grain stack”, due to its unusual appearance. It is tall in the middle, narrow at the bottom, and completely flat on the top, meaning it resembles a stack of wheat. So be careful when you take photographs of this scenic spot, or they might come out a little grainy! The caves are separated by number, with numbers 1 to 50 on the western cliff-face and numbers 51-191 on the eastern cliff-face.

The mountain itself sits at an altitude of 1,700 metres (5,577 ft.) and is named “Maiji”, meaning “wheat”, “corn”, or “grain stack”, due to its unusual appearance. It is tall in the middle, narrow at the bottom, and completely flat on the top, meaning it resembles a stack of wheat. So be careful when you take photographs of this scenic spot, or they might come out a little grainy! The caves are separated by number, with numbers 1 to 50 on the western cliff-face and numbers 51-191 on the eastern cliff-face. Construction of the grottoes reached its peak during the Northern Wei (386-535), Western Wei (535–557), and Northern Zhou (557-581) dynasties, but continued well into the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, representing over 1,000 years’ worth of effort and artistry. The earlier caves are far more simplistic in design and mainly feature a seated Buddha flanked by bodhisattvas

Construction of the grottoes reached its peak during the Northern Wei (386-535), Western Wei (535–557), and Northern Zhou (557-581) dynasties, but continued well into the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, representing over 1,000 years’ worth of effort and artistry. The earlier caves are far more simplistic in design and mainly feature a seated Buddha flanked by bodhisattvas The bodhisattvas who usually accompany Amitābha are Avalokitesvara on his right and Mahasthamaprapta on his left. Avalokitesvara is the most identifiable, as he is typically depicted with an image of Amitābha on his headdress and a small water flask in his hands. In a few more hundred years, Avalokitesvara will change genders and eventually reappear in the grottoes as the bodhisattva of mercy, known as Guanyin. That being said, when it comes to eternal enlightenment, it doesn’t really matter if you’re a man or a woman! Other statues include those of the historical Shakyamuni

The bodhisattvas who usually accompany Amitābha are Avalokitesvara on his right and Mahasthamaprapta on his left. Avalokitesvara is the most identifiable, as he is typically depicted with an image of Amitābha on his headdress and a small water flask in his hands. In a few more hundred years, Avalokitesvara will change genders and eventually reappear in the grottoes as the bodhisattva of mercy, known as Guanyin. That being said, when it comes to eternal enlightenment, it doesn’t really matter if you’re a man or a woman! Other statues include those of the historical Shakyamuni

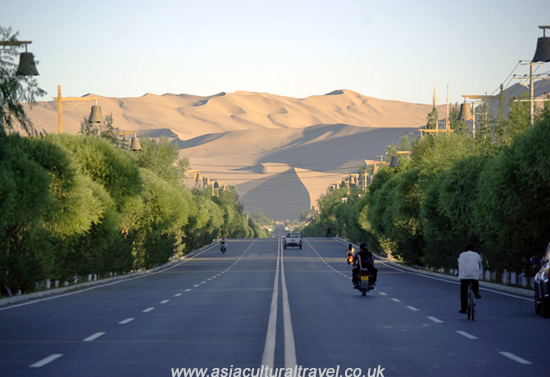

China owns the largest distribution of yardangs in the world and, of these, Dunhuang Yardang National Geopark contains the lion’s share. Exhibiting over 300 square kilometres (116 sq. mi) of yardangs, it covers an area over 100 times the size of the city of London! It’s rumoured that, if you use your imagination, some of these them begin to look like famous world sites, such as the Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Pyramids of Egypt. That being said, to you they may all just look like rocks!

China owns the largest distribution of yardangs in the world and, of these, Dunhuang Yardang National Geopark contains the lion’s share. Exhibiting over 300 square kilometres (116 sq. mi) of yardangs, it covers an area over 100 times the size of the city of London! It’s rumoured that, if you use your imagination, some of these them begin to look like famous world sites, such as the Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Pyramids of Egypt. That being said, to you they may all just look like rocks!